Stickers, buttons and pictures of the 2020 presidential hopefuls hang alongside memorabilia from elections past at the State House visitor centre in Concord, N.H. The state holds the first primary of the U.S. election season on Feb. 11, and only the second party contest after the Iowa caucus on Feb. 3.JOSEPH PREZIOSO/JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images

David Shribman, the former executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, won a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of U.S. politics.

Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts stands before an audience in this impoverished paper-mill town closer to Ottawa than Washington and introduces her dog and her husband.

Representative Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii fields questions in a brew pub at the base of an old ski resort about why an unknown House member should be taken seriously as a presidential contender.

Former Republican governor William Weld of Massachusetts pokes at a lunch tray filled with Salisbury steak, mashed potatoes, corn and Caesar salad in the seniors’ centre in the ski town of North Conway, entertaining questions from fellow diners about his quixotic challenge to President Donald Trump in the Republican primary here.

This is how candidates campaign for the most powerful job in the world in one of the smallest, least diverse, most remote corners of the United States.

It is an accident of history, not geography, that made New Hampshire, which holds its critical primary election Tuesday, an important testing ground. It is not in the middle of anything, except for Massachusetts and Quebec. It is not a microcosm of anything, except for surly independence. It is not a bellwether for anything, except maybe for orneriness, which follows no established patterns.

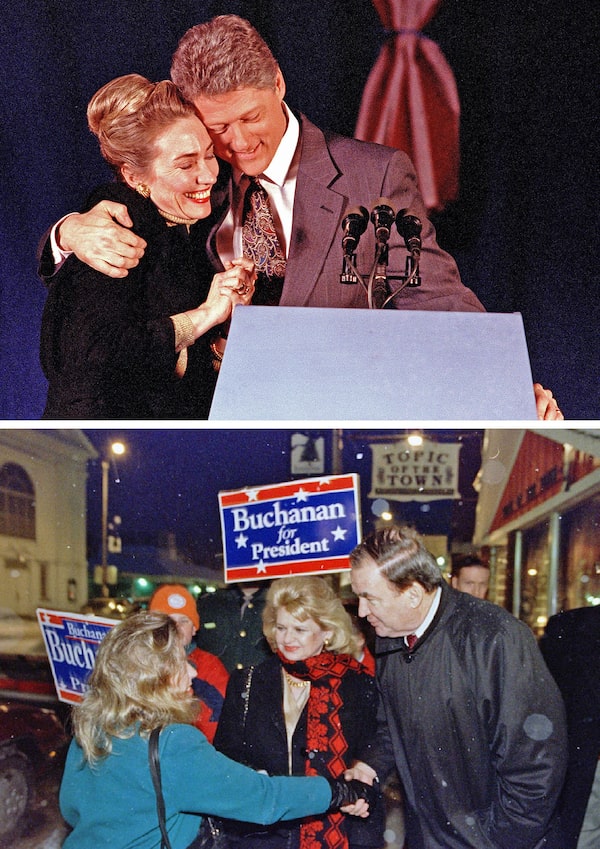

That is why, from time to time, the state’s vaunted primary has been captured by men such as Democratic iconoclast and former senator Paul Tsongas as well as Republican firebrand Nixon and Reagan speechwriter Patrick Buchanan in successive 1990s primaries. The two eventually went nowhere but home. But they gave a sufficient scare to Arkansas governor Bill Clinton (1992) and Senate majority leader Robert Dole (1996), who eventually did win their parties’ nominations. In cases like that, New Hampshire has been a crucible but not a coronation.

Democrat Bill Clinton and wife Hillary (top) and Republican Pat Buchanan and wife Shelley (bottom) at the New Hampshire primaries in 1992 and 1996, respectively. Mr. Clinton came in second in New Hampshire but won the nomination and election; Mr. Buchanan came in first in New Hampshire but lost the nomination to Bob Dole, who lost the election to Mr. Clinton.The Associated Press, Reuters

It is where Democratic senator Gary Hart of Colorado developed a grassroots style of politics that won him the 1984 primary and established the ethic of the New Hampshire ground game – build a solid organization, maybe out of sight of the political pros – that prevails to this day. It is where Republican senator John McCain of Arizona prevailed against a better-financed Texas governor George W. Bush in 2000 by holding scores of town hall meetings across the state, a political art form that the 2020 candidates still seek to perfect.

Over the years, the primary here has provided multiple memorable moments: the dour Republican senator Robert Taft of Ohio holding a rooster in 1952 and looking as if he were about to crow – or croak; activists organizing a write-in campaign for a candidate 14,000 kilometres away, helping the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge, win the 1964 GOP contest even though he wasn’t on the printed ballot; college students from all over New England getting “clean for Gene” by cutting their hair and shaving their beards in 1968 to canvass house-to-house for anti-Vietnam War Democratic senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota; senator Edmund Muskie of Maine crying, or appearing to cry, as he defended his wife’s honour in the 1972 Democratic primary; social worker Ned Coll holding up a rubber rat to bring attention to the issue of urban poverty in a 1972 debate; Democratic representative Morris Udall of Arizona approaching a group of elderly voters during the 1976 primaries and telling them he was running for president – only to hear one of them say, “We were just laughing about that”; vice-president George H.W. Bush salvaging his 1988 GOP prospects with a coffee visit to the unlikely setting of Cuzzin Richie’s Truck Stop; senator John Glenn of Ohio, a former astronaut, encountering twins on the sidewalk of a New Hampshire lake town in 1984 who were born the year he became the first American to orbit the Earth and discovering that one was named John and the other Glenn; Mr. Hart hurling a double-edged axe directly at a bull’s-eye in 1984. And so much more.

So central to politics – and journalism – is this state’s primary that the bar stool favoured by legendary campaign chronicler Jack Germond in the old Sheraton Wayfarer Hotel in Bedford, just outside Manchester, was moved to the Newseum in Washington with great fanfare. Mr. Hart, in a visit to the bar, once said that “more lies have been told in this room than in any room in America.” The hotel closed in 2010. Mr. Germond died in 2013.

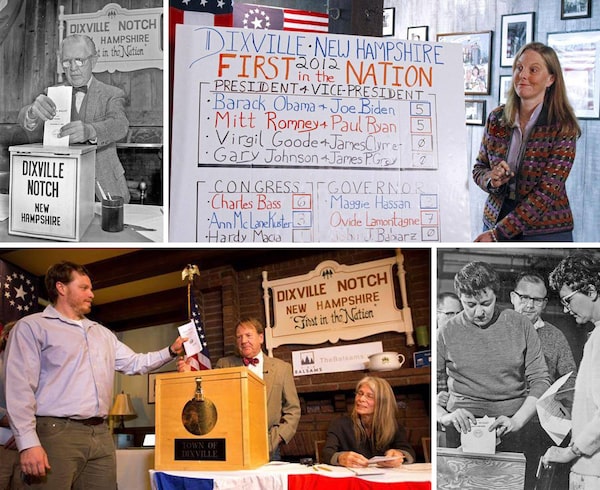

Dixville Notch, N.H., is a tiny community with a big responsibility: In the first primary of the U.S. election season, its voters cast their ballots at midnight, making them the first Americans to vote each year. The proprietor of the Balsams resort began the custom in 1960. Clockwise from left are the voting days from 1984, 2012, 1964 and 2016. Dixville Notch nearly had to scuttle it this year because its population was too small and an essential polling official had moved away, but they found a replacement in time.The Associated Press, AFP/Getty Images

The first New Hampshire primary was in 1916, but it didn’t acquire its current importance until 1952. Often the primary was held on Town Meeting day; frugal Granite Staters didn’t want to heat their tiny civic halls twice in the winter.

The state has gone from an idiosyncratic form of conservatism to a crunchy-granola liberalism, but three elements of its culture remain unchanged: granite independence, to match its forbidding mountains; an aversion to taxes – it’s the only state without a broad-based levy such as an income tax or a sales tax; and an adamantine devotion to preserving its primary as the “first in the nation.”

So devoted to that notion is the state that its politically involved residents – which is to say most of them – simply employ “FITN” to describe New Hampshire’s position, assailed every four years but defended successfully every time, at the front of the parade of U.S. primaries. (And no, they don’t count the Iowa caucuses – they just don’t.) If you have to ask what FITN means, then you obviously aren’t from around here.

New Hampshire is a state of folklore, befitting a place where the Ivy League college, Dartmouth – itself a repository of legends, many patently false – is pronounced “Dart-myth.” One element of this folklore – actually distributed formally in a briefing paper written by the New Hampshire Historical Society, but believed devoutly from the seashore to the White Mountains – is that “we take politics as a civic responsibility."

Like all myths, there is a kernel of truth to this one.

Candidate Joe Biden speaks at a Feb. 5 campaign event in Somersworth, N.H.Elise Amendola/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

The locals like to say – it is an appealing notion the first 150 or so times you hear it, a little less beguiling after that – they can’t decide which White House aspirant to support until they meet all the candidates at least twice. For some it is a preoccupation, for others an obsession. It has been harder this time around, of course, with more than two dozen Democratic candidates at the start of the campaign, a number that has dwindled to 11.

Last July, for instance, fully seven months before the primary, 13 presidential candidates visited the state in the first 13 days of the month – in 57 separate political events. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York State, who later withdrew from the race, did 13 events herself. One of them was a 7:45 a.m. spinning class, taking the notion of citizens exercising their political rights to a bizarre extreme.

“I want to meet them all,” said Mike Dowe, a Gifford, N.H., radiologist. “New Hampshire is special, and I want to take advantage of the opportunity to do that. We take the presence of all these candidates for granted.” By mid-July, he had already met 10 of the candidates and had plans to add a few more each week.

Elizabeth Warren at a Feb. 6 campaign event in Derry, N.H.Matt Rourke/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

In the old days, as now, the campaigning here was intimate, personal. In 1976, student panelists interrogated all the candidates who appeared on the Dartmouth College campus. One was Paul Gigot, now the editorial page editor of The Wall Street Journal. Another was Robert Saltzman, emeritus associate dean of the University of Southern California Law School. “The candidates in New Hampshire really have to meet the people, deal with them face to face and answer their questions,” Mr. Saltzman said. “And if you don’t get an answer the first time, you very likely will run into a candidate somewhere else and have a chance to try again.” He wasn’t satisfied with an answer Mr. Udall gave him and had several other chances in the following weeks to press him again.

“The New Hampshire primary is not something that happens on one day," the late New Hampshire governor Hugh Gregg once told me. “It is the longest-lasting convention in the United States. It lasts four years.”

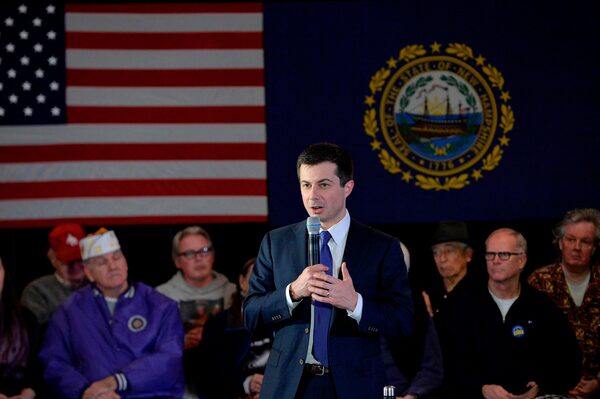

That, too, is part of the New Hampshire ethos. “There’s an expectation of involvement here,” candidate Pete Buttigieg of Indiana said in an interview here last month. “There’s a sense of commitment and responsibility."

Pete Buttigieg at a Feb. 6 town hall in Merrimack, N.H.JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

But the character of the state has changed dramatically since Mr. Gregg’s prominence in the Eisenhower years.

Once regarded as a faraway mountain fastness, known principally for its textile industry and boasting only one even marginal city (Manchester), New Hampshire has long since ceased being a state of hewers of wood and carriers of water; indeed, the forest industry has been in decline for more than half a century, and there hasn’t been a mill built, or even maintained, in decades.

Much of it is rural and yet not congenial to farming; in his landmark book about the White Mountains, John T.B. Mudge wrote that the soil was “thin, cold, and filled with rocks that had been left indiscriminately by the last glaciers.” As long ago as 1964, New Hampshire was developing an industrial base – now principally high tech, accounting for 69,888 jobs, according to the latest Computing Technology Industry Association figures – that conflicted with its rural profile.

The passage from Mr. Gregg’s governorship (1953-1955) to that of his son, Judd Gregg (1989-1993), is instructive. In the elder Mr. Gregg’s day, New Hampshire had poor roads, poor schools, poor economic prospects and poor if not non-existent television reception. In some communities, dentistry was little known or poorly practised. By his son’s day in the governor’s chair in Concord, two major federal highways made travel easy (or at least passable) even in winter, school groups were making field trips to Washington or even overseas, and cable television had ended the state’s isolation – it was even possible to get more than one channel.

At the same time, southern New Hampshire became something of a suburb of Boston. Many of its residents had been drawn to the state because of its low taxes, but they watched Boston television, wore Bruins regalia and worked in Boston or along the Route 128 technology corridor. As northern New Hampshire hollowed out, the southern part of the state bustled, at least through the first decade of the new century.

Today’s New Hampshire, however, is marked by the slowest population growth since the decade beginning in 1910 – along with low unemployment and a rapidly aging citizenry. While those 55 and over comprised one in seven workers two decades ago, today they account for more than one in four. “The limitation in the number of available workers might add roadblocks to companies’ ability to expand,” according to a recent report from the state’s Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau.

'Live Free or Die' licence plates are for sale at the State House in Concord.JOSEPH PREZIOSO/JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images

Through all this change – more dramatic here than in any other corner of the United States except perhaps the Research Triangle of North Carolina – New Hampshire held fast to its primary and to the folklore that animates its politics to this very day, when “Live Free or Die” – an excerpt from an 1809 letter by the state’s Revolutionary War hero, John Stark – remains atop the state’s licence plate, a kind of Yankee Je me souviens.

And, much the way Canada’s outback provides the moral oxygen for the country despite its small population, the remote mountains of New Hampshire remain a sturdy part of its sense of place. In 1784, Jeremy Belknap, who had been the chaplain to the New Hampshire troops in the 1775 siege of Boston, climbed Mount Washington – at 1,917 metres, the highest peak in the U.S. Northeast – and looked down on Pinkham Notch, now a popular staging area for hikers, and spoke of what he saw: “Almost everything in nature, which can be supposed capable of inspiring ideas of the sublime and beautiful is here realized. Aged mountains, stupendous elevations, rolling clouds, impending rocks, verdant woods, crystal streams, the gentle rill, and the roaring torrent, all conspire to amaze, to soothe and to enrapture.”

Today’s New Hampshire residents wouldn’t change a word of that – even if they ascend Mount Washington by car, on the old 12.2-kilometre carriage road that goes up its western spine, and wear hiking boots solely as a fashionable accoutrement.

The midday sun rises over New Hampshire's Mount Washington.Robert F. Bukaty/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

There is, to be sure, poetry in the fact that the state’s formidable mountains have a section called the Presidential Range, but those names – Mount Washington, Mount Adams, Mount Jefferson and so on – preceded the ascendancy of the New Hampshire primary, though Mount Eisenhower was added later. The name Mount Reagan, adopted by the state legislature in 2003 for a 1,686-metre peak, never caught on and indeed has been rejected by federal authorities, who have jurisdiction on place names.

But New Hampshire’s most famous poet, Robert Frost, has contributed to the state’s reputation for straight talk and civic virtue. In his poem New Hampshire – published in 1923 within the book of that title, which won him the first of his four Pulitzer Prizes – he said he fled to the state because it was the “nearest boundary to escape across,” adding:

I hadn’t an illusion in my handbag

About the people being better there

Than those I left behind. I thought they weren’t.

I thought they couldn’t be. And yet they were.

JOSEPH PREZIOSO/OSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.