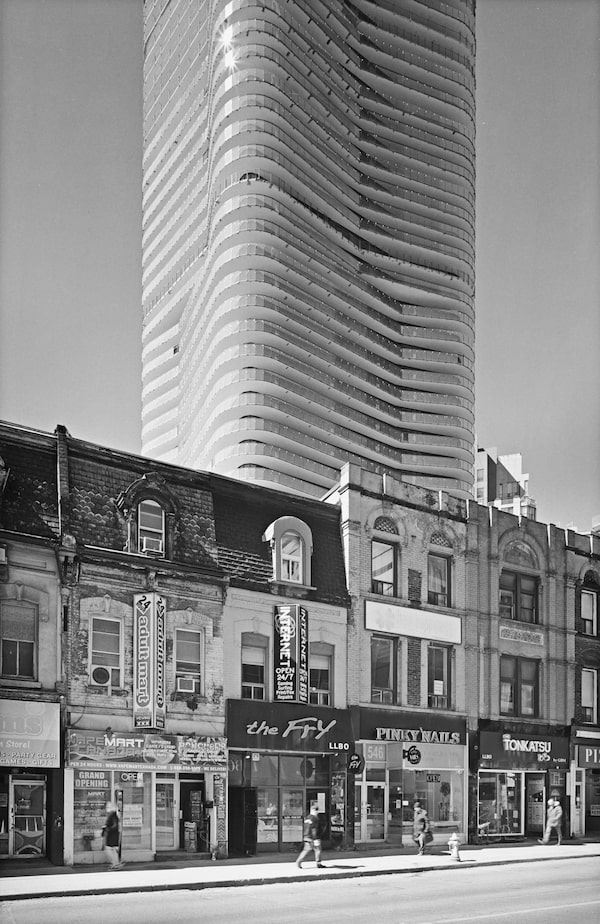

The neoclassical Bank of Toronto (left) and Canadian Bank of Commerce buildings both date from 1905. They are dwarfed by the 60-storey Massey Tower by MOD Developments, now nearing completion. Between the two banks is the former site of the Colonial Tavern, a storied Toronto jazz club. It will become the entrance to a luxury retail mall.Photography by Peter MacCallum/Peter MacCallum

Peter MacCallum is a self-taught architectural photographer. Since 2000, he has undertaken projects on streetscapes in Toronto, Montréal and Paris.

The great American photographer Walker Evans once said, about his own work, that he was “interested in what any present time will look like as the past.”

This statement became the starting point for my photography project on the architectural fabric of lower Yonge Street, in downtown Toronto.

Documentary photography of urban streetscapes dates from the earliest years of the medium. Most often, it has been commissioned to illustrate redevelopment projects involving architects, planners, politicians and administrators. The architectural historian Vincent Scully characterized architecture as a conversation between the generations, carried out across time. Streetscape photography shows how buildings at different stages in their lives appear together at a precise moment in a city’s development. I find that black and white photography serves the purpose better than colour.

The Halo condominium site looking south from Grosvenor Street. The surviving tower of Firehall No. 3, dating from 1872, marks the site of the St. Charles Tavern, a landmark of Toronto’s LGBTQ history, which opened in 1950 and closed in 1987.

When I began my streetscape project in 2007, construction of the 79-storey Aura condominium at Yonge and Gerrard, the first, and arguably the least objectionable of the current wave of high-density developments, had not yet begun. I was amused to discover that a few buildings on this strip had been built at the lowest possible density. The monumental signage above the entrance to the Little House of Kebabs (now Ali Baba) was one of several instances of false fronts hiding single storey structures of concrete block.

When I returned to lower Yonge Street in March, 2019, to add an update to my earlier project, I was faced with the problem of showing the extreme disparities of scale and architectural form between the older two and three storey commercial blocks and the towers of 60 to 90 storeys that had just been completed or were still under construction. Huge, clumsy podiums resembling faceless science-fiction monsters were pushing neighbouring blocks aside.

While century old retail buildings were being demolished, some facades were being carefully preserved, later to be attached to the fronts of new glass boxes. Perhaps we should applaud any attempt to preserve the historical integrity of the streetscape, but these once-dignified storefronts are being cheapened by their association with rampant commercialism.

Dilapidated 19th-century facades on the west side of Yonge Street south of Wellesley. In the background, the 11 Wellesley St. condominium tower under construction.

As an architectural photographer, what I found most oppressive about several of the new towers was the blank appearance they maintained throughout the day, even under the most dramatic lighting conditions. These projects could be said to have failed the transition from a CAD program on the architect's computer screen into three dimensions. When compared with Toronto’s better skyscrapers dating back to the early 1900s, they appear as lifeless duds cluttering the skyline.

The idea of having two skyscrapers at Bloor Street forming a gateway to lower Yonge Street is worth considering in principle, but in order for it to be expressed as architectural form, the two buildings would have to be visually compatible. That is not the case with the recently completed 76-storey glass-clad tower by Hariri Pontarini Architects at the southeast corner of Bloor and Yonge, and the 85-storey exoskeleton structure by Foster and Partners currently under construction at the southwest corner. The two towers have been named “One Bloor” and “The One” by their respective developers. Each wants the public to see its own building as a singular architectural achievement and ignore the fact that it is too big for its site and doesn’t have any visual relationship with its neighbour. In reality, I expect these buildings are going to loom over pedestrians like Scylla and Charybdis.

When the gateway is completed, it will be my job as a documentary photographer to make a visual record of the resulting streetscape. I will try to maintain a rigorously objective approach to the subject, but I fear that the images I manage to produce won’t make a pretty picture.

The podium of the 76-storey One Bloor condominium tower will become the eastern side of an uncoordinated monumental gateway to Lower Yonge Street.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.