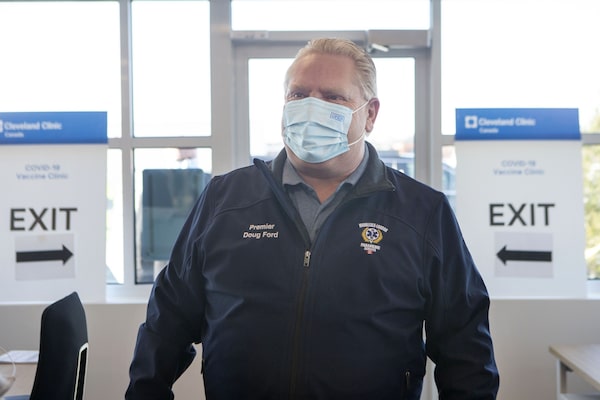

Ontario Premier Doug Ford arrives at a vaccine clinic for Purolator employees and their families at the company's plant in Toronto on Jan. 7.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

Ontario Premier Doug Ford seemed stumped – and, absurdly, caught off guard – when he was asked recently about how the province was going to fortify safety measures in classrooms during the time afforded by a return to virtual learning. The Premier, who had sent the province’s kids home three times before in the past two years, didn’t have an answer ready for this fourth stint of online school. He mumbled something about “enhanced cleaning,” N95 masks and rapid tests, while an inaudible message of bureaucratic panic, sheepishness and regret lingered in the air: Whoops, we probably should have planned for this.

It was a sign – as if one was needed for anyone who has lived through this government’s anemometer approach to pandemic planning – that the decision to keep kids out of school for the first two weeks of the year was based on the science of polling, not epidemiology.

The Premier could not explain why virtual schooling was necessary when, unlike during previous school shutdowns, most adults in the province had been vaccinated and some children had started to receive their vaccines. Mr. Ford did not address research that appears to indicate that school outbreaks are reflective of community spread, not drivers of it, or that science table modelling showed astronomical Omicron growth with or without circuit-breaker measures. The province provided no metrics by which it would determine whether a return to in-person learning after two weeks was feasible, nor did it give much heed to the staffing challenges that would arise in health care and other sectors by forcing parents to stay home and supervise their children.

If the reason for delaying in-person learning was ultimately to try to prevent Ontario’s hospitals from becoming overwhelmed, it doesn’t follow that the Ontario government would confirm on Tuesday – with still nearly a week yet to go – that students will return to classes next week as planned. There are few indications that Omicron’s effect on hospitals has peaked, and the number of patients in hospital with COVID-19 (which, it should be noted, includes incidental cases) has reached a pandemic high. Indeed, if concerns about the health care system were the point, then the province would have at least waited to see some evidence that the effect of this wave was subsiding. That evidence is not there, yet parents have been told to prepare for in-class learning anyway (which could change by Sunday evening).

The Ontario government is now emphasizing the steps it is taking to make schools safer: high-quality masks for all teachers, more HEPA filters in classrooms, accelerated booster shots for educators, PCR tests for symptomatic students. It has also relaxed rules that previously limited the number of days retired teachers could work as supply teachers in anticipation of absences because of the prevalence of Omicron, though it is doubtful many pension-aged individuals will want to step into classrooms of students where the regular teacher is off sick.

These measures may or may not stave off major outbreaks in schools and classrooms (and we may never know since PCR testing has been limited and schools will no longer be routinely informing students of a positive case in their classrooms, according to the latest guidance from the Ministry of Health). But they still do not explain why it was necessary keep kids out of school for the first two weeks of January. After all, the province already had two weeks for the Christmas holiday during which it could have procured N95 masks, prioritized educators for boosters and sent HEPA filters to schools.

Mr. Ford could almost be forgiven for jerking kids around for two years – for subjecting children and their parents to the enormous emotional strain of enduring instability, among other things – if it was apparent that these decisions were being made because of an unyielding fidelity to precautionary principles. These decisions still would have largely neglected the mental-health effects of rolling lockdowns and school closings, but at least they would’ve been rooted in a genuine desire to preserve the physical health of the greatest number of people in Ontario. The absence of a clear, empirical explanation for closing schools in January – and, even more conspicuously, for announcing they will open now, as hospitalizations are climbing – indicates that something else is driving these decisions. It’s pandemic planning by polling, with children as the collateral damage.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

Robyn Urback

Robyn Urback