Illustration: THE GLOBE AND MAIL. SOURCE IMAGE: ISTOCK

Dan Gardner is a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs. His books include Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear and Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.

If you think the unemployment rate is a wonderfully low 3 per cent but I think it is a frighteningly high 15 per cent, and we both have sources that tell us we are right and both think the other person’s sources are untrustworthy, we cannot have a conversation about unemployment. You are shocked that I am so misinformed; I am appalled that you are so deluded. Nothing you or I say can change that. The best we can hope for is that this encounter doesn’t end in angry words and insults.

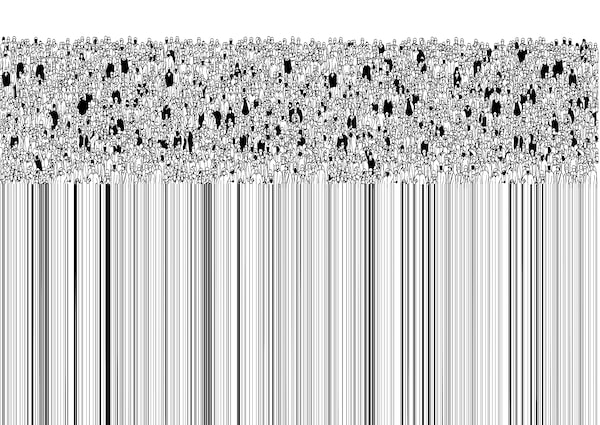

Anyone who has spent time on social media is familiar with this dynamic, but it is hardly confined to Twitter and Facebook. One of the essential features of this era is the division of so many people into little tribes of the like-minded, each bewildered that other tribes believe the crazy things they do. It has many sources. And it’s likely to get much worse very soon, making meaningful public discussions increasingly difficult. Some have called it nothing less than an existential threat to democracy.

There is no universally accepted name for the phenomenon, but researchers at the RAND Corporation have suggested “truth decay.” They see four elements: increasing disagreement about facts, a blurring of the line between opinion and fact, the rising volume and influence of “opinion and personal experience over fact” and, perhaps most critically, “declining trust in formerly respected sources of facts.” Remember presidential adviser Kellyanne Conway defending blatantly false claims by calling them “alternative facts”? That’s truth decay.

This wasn’t how the 21st century was supposed to unfold. We were told that the Information Age – the great cliché of the 1990s – would be an era of wonderfully informed citizens having thoughtful discussions in the digital agora. It would be ancient Athens with candy-coloured Macs and hacky sack.

But what few recognized 20 years ago was how that bright future could be undone by basic elements of human psychology. For one thing, people generally enjoy having their views confirmed, not questioned, a tendency psychologists call confirmation bias. We also prefer to keep company with the like-minded, and when we do our views become more extreme, a process known as group polarization. It should have been obvious that search engines and digital connectivity could narrow minds as easily as open them.

As the years went by, tech companies added algorithms designed to find and offer more of what people like, creating “filter bubbles” that keep out the contrary or disagreeable. Then came social media, with its dopamine-rewarded likes and blocks and group pile-ons. At the same time, the business models supporting news intended for mass audiences started to break down, while narrowly targeted digital information sources exploded. Reporting withered. Opinion flourished.

Add the crisis of 2008 and heightened financial insecurity. Toss in partisan polarization, particularly in the United States.

And throughout it all, a long-term decline in social trust continued, diminishing the authority of politicians, governments, corporations, journalists and other sources of information. There can be no Knowlton Nash or Walter Cronkite today.

Most recently, Vladimir Putin’s intelligence services figured out how to make brilliant use of this new environment. Russia’s keyboard insurgents push both sides of every argument, whether it’s Black Lives Matter, gay rights, vaccine safety or even Beyoncé’s controversial appearance at the Super Bowl. In one notorious case, Russians organized and promoted an anti-Islam protest – and the counterprotest. The goal isn’t to promote an ideology, it’s to accelerate division.

That’s the story so far. It’s grim. But a new factor may soon make things much worse.

Its statistics are so routinely cited as fact by all parties, factions and interests that “Statscan says” is effectively a Canadianism meaning “the following is true.”

So-called “deep fakes” look like video and audio of real people but are actually AI-generated images. The tech that makes them is cutting-edge today but will soon be commonplace, giving any intelligent and determined person the ability to create a video of almost anyone doing or saying almost anything. Imagine what the malicious will do with it. But worse than the frauds will be the shadows of doubt they cast: Consider that in 2013, when video of late Toronto mayor Rob Ford smoking crack was reported to exist but hadn’t yet turned up, Mr. Ford’s more extreme supporters insisted there probably was no video, but if it did exist, it had to be a computer-generated fake. In 2013, that was absurd. So when the video surfaced, the facts were inarguable. But in 2023? Those who wish to believe a video is real will believe it, while those who don’t won’t.

Add it all up and the Information Age we are headed toward is starting to look less like a diverse digital agora and more like a barren landscape of hostile tribes glaring at each other in mutual incomprehension. Forget the Athens of Aristotle. It will be the Peloponnesian War.

What’s a democracy to do? The potential for policy to make a difference is limited, but at least one practical step should be taken immediately. In this era, trust is worth more than gold. An institution that enjoys near-universal trust is a treasure. And if that institution’s job is to churn out the facts that are democracy’s currency? It is nothing less than a national treasure.

We have such an institution. It is Statistics Canada.

Nine in 10 Canadians have heard of the agency, and eight in 10 have a positive impression. Its statistics are so routinely cited as fact by all parties, factions and interests that “Statscan says” is effectively a Canadianism meaning “the following is true.” It’s hard to overstate how valuable that makes this dull little agency.

In 2016, when then-candidate Donald Trump found the low and falling U.S. unemployment numbers to be inconvenient, he loudly and repeatedly dismissed them as fraudulent, then substituted others – “probably 28, 29, as high as 35 … in fact, I even heard recently 42 per cent” – from unnamed sources. He took little heat for it. Nor did he suffer when, as President, he started bragging about the same stats produced with the same methodology by the same agency. That’s because the agency is the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS), an obscure bureaucratic outpost most Americans don’t know or respect the way Canadians do Statistics Canada.

A Canadian politician could never get away with the brazen daylight vandalism Mr. Trump inflicted on the BLS. Just look at the uproar when then-prime minister Stephen Harper attempted the comparatively subtle pickpocketing of Statscan’s census.

We need to make much greater use of this treasure.

While Statistics Canada is currently examining various forms of modernization – mostly looking for more innovative ways to generate data – much more fundamental reform is needed. The act establishing Statscan, the Statistics Act, needs four amendments.

The first is simply a preamble stating that Statscan exists to produce the trusted information that is essential to Canadian democracy.

Then Statscan’s current remit of developing data about Canada must be expanded to Canada and the world. In a globalized society, informed discussion needs global information.

Statscan must also be directed to do far more than generate statistics and compile data from other branches of the federal government. It must reach out to credible agencies around the world – the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund, the much-abused BLS and many others – to compile their existing data sets, scrutinize them to ensure their methodologies meet Statscan’s high standards and publish them – while carefully noting what is and isn’t comparable. In this way, the volume and variety of information Statscan delivers to Canadians could be hugely increased. And because it would all come with the agency’s seal of approval, it would be trusted. Statistics Canada would become the information clearinghouse of Canadian democracy.

Finally, Statscan must be told communication is a core part of what it does. Officials will insist it already is. It isn’t. The agency’s communications are desultory and antiquated. Information technology has produced a cornucopia of amazing data-visualization techniques, and there is a vast amount of research literature on data and science communication. Statscan must put it all to work in the service of ordinary Canadians.

For decades, Statistics Canada has been taken for granted. As the country and the world became bigger and more complex, the agency was underfunded and could not keep up. Experts in many fields have long complained that its output is sparse, patchy and slow. Merely making up lost ground would require major investment. Recognizing the threat of truth decay, and the indispensable role Statscan could play in fighting it, would multiply the cost.

But democracy is worth it.

Incidentally, the unemployment rate is neither 3 per cent nor 15 per cent. It is 5.9 per cent. I know that is true because Statscan says so.