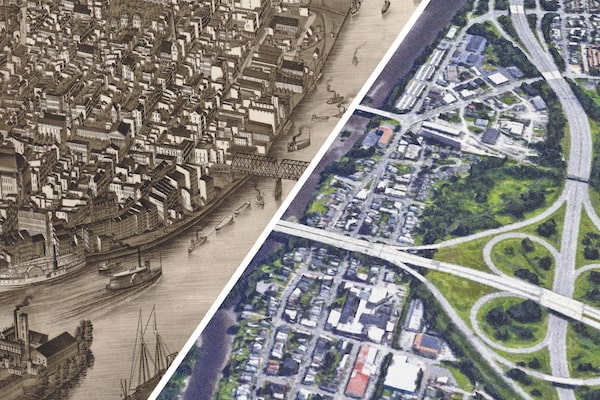

Troy, N.Y., illustrated at left as it looked in 1881, was a thriving city more densely vertical than it is today. On the other side of the Hudson River lies Watervliet, as represented in a matching Google Earth view.U.S. Library of Congress, Google Earth

Reif Larsen is a writer and the founder of the Future of Small Cities Institute.

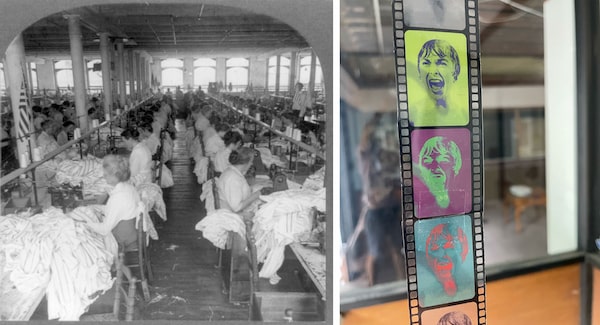

Entering the glass vestibule of a former jewellery store in downtown Troy, N.Y., I found myself surrounded by a cluster of translucent helium balloons, their strings replaced with dangling filmstrips from classic movies such as Psycho, each frame of Janet Leigh’s visage pigmented in bright chromatics à la Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe series. Halfway between sidewalk and storefront, it was as if I were momentarily suspended in the transparent time capsule of the celluloid itself.

I paused on this threshold, marveling at the archeology of our urban spaces. The large building that housed the storefront was once a bustling Masonic Temple, site of much ritual and scroll unfurling, before a 1970s “urban renewal” program awkwardly readapted its cavernous interior into the Rensselaer County Senior Center. In 2019, tech-entrepreneur Bob Bedard bought the deteriorating building with plans to transform it into a regional Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence.

These balloons now subsuming my entrance were a mini design intervention by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute architecture student Alexandrea Agyekum, whose design studio, led by artist Michael Oatman, was studying the empty storefront as the site of a pop-up exhibition space.

Their first show, mounted for a week in September, 2021, was an exhibition on the history of exhibitions — the space was filled with videos, posters, installations and cabinets of curiosity that the students had installed overnight. Ms. Agyekum was exploring the ephemeral, sensory journey of entering a ground-floor space — what draws us in off the sidewalk? What makes these houses of retail a cultural ritual, a spectacle, a collective experience?

My organization, The Future of Small Cities Institute, was working with Prof. Oatman’s class to transform the storefront into a kind of “urban room” that would host a series of exhibitions on sustainable city design solutions, beginning with a show on the past, present and future of Hudson River waterfronts in the spring of 2022.

Such is the way in these small, postindustrial cities like Troy, with a population of just over 50,000, where collaboration, experimentation and adaptation bloom, often out of necessity.

Hamstrung by tight budgets, stretched workers and innumerable capacity issues, these small legacy cities across North America are forced to lean into public, private and community partnerships to solve the myriad challenges posed by their aging urban landscapes. There is never enough time, money or resources in these cities, yet owing to the compact size of their urban footprints, small, nimble projects and initiatives can have big effects.

For years, these small legacy cities – gutted by a loss in manufacturing, pockmarked by abandoned industrial spaces, and hampered by a dwindling population – have struggled to make a sustained economic recovery. Yet the tides may finally be shifting. The rapid expansion of hybrid and remote workplaces during the pandemic, along with a climate crisis that has underscored the vulnerability of our bigger cities and laid bare the necessity for community resilience, has suddenly made places like Troy ripe for adaptation in the 21st century.

This, then, has become the central question for small cities: Can they harness their flexibility and transition from spaces of disinvestment to sustainable, inclusive communities? Balancing smart, innovative development with the continuing challenges of equity in a post-COVID (or COVID-endemic) world remains a tall task for any city – big or small. And perhaps there is no better place in which to witness this evolution than the complex stage of the small-city Main Street.

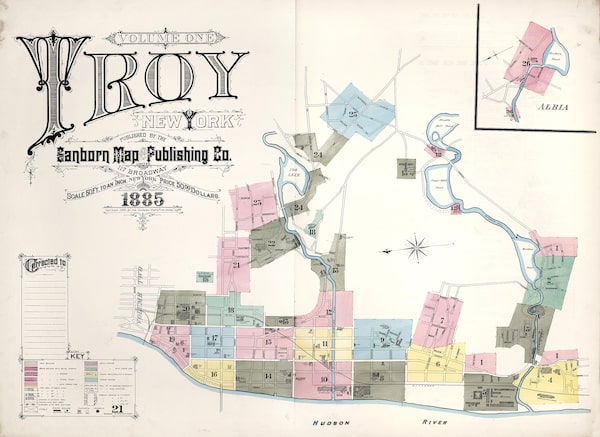

Scenes from ancient Troy: A map from the 1880s, and photos of Union Station and City Hall in the 1900s. As manufacturing jobs dwindled, the city developed a sketchy reputation and an unfortunate nickname: Troy-let. Today, Troy is home to just over 50,000 people.U.S. Library of Congress

The Troy Waterfront Farmers Market, which closes several blocks of River Street each Saturday and attracts more than 14,000 people from around the region, was a huge factor in transforming Troy’s downtown from a no-fly zone just 10 years ago to the vibrant cornucopia of shops, eateries and services that it is now.

The model of the farmer’s market, a now-ubiquitous urban intervention with roots in the ancient bazaar – the original Main Street – is deceivingly revolutionary in how it asks us to reimagine entrenched, late-20th century ideas of streetscapes, food systems and retail architecture: Streets can be for people; food systems can be deeply local and circular; retail space can be lightweight and flexible.

“The market is a sensory experience,” said Stephen Ridler, who manages the farmer’s market. “With a market booth, the whole store is the storefront. There’s a transparency there, and at the same time you can be walking in the middle of the street, looking at all this historic architecture around you.”

This turns out to be one of the pillars to downtown revitalization: Give people a reason to get out of their cars and walk and linger and touch the surfaces of your town.

“You can just do stuff here,” said Vic Christopher, as we sat outside his café, Little Pecks, on a crisp, early-fall day. Mr. Christopher is a kinetic character with a central casting jaw line and a lilting Brooklyn accent. He’s often cited as being instrumental to downtown Troy’s turnaround when he bought a cluster of buildings at the corner of Broadway and Second Street and, in 2012, decided to open Lucas Confectionery, a wine bar, in the site of a former candy store.

“There was nothing around,” said Mr. Christopher, chuckling at the memory. “And people were like, ‘You’re crazy! You can’t open a wine bar in downtown Troy.’ ”

Like many small cities, Troy had undergone a traumatic transformation during the late 20th century with the great shift in work force away from manufacturing and the hollowing of its commercial corridors. The city saw a rise in poverty, drug use and crime over the decades since and downtown Troy had gained a reputation in the region for a kind of entrenched sketchiness.

As evidence of the problematic divide between city and suburb, a friend of mine who grew up in wealthy neighbouring Niskayuna knew of Troy in the 1990s only as the place where she would occasionally go to buy weed and then leave as quickly as possible. To make matters worse, the city had long suffered from poor management, corruption and a cycle of never-ending debt. The term “Troy-let” was used quite liberally.

But to everyone’s surprise, people did go to Lucas Confectionery, and more restaurants followed – there are now more than 70 establishments in downtown Troy alone. The downtown’s remarkable turnaround, driven in large part by private enterprise, has now entered into local lore. As part of this phalanx of enterprise, Mr. Christopher’s collection of ventures is a constantly evolving blend of mainstays and experiments that stretch around a city block, including a wine shop, a conservatory workspace, a small grocery store and a new wood-fired pizzeria.

I moved to Troy about four years ago after my wife landed a teaching job here. We moved 50 miles north from the village of Saugerties in the mid-Hudson Valley, and we caught a gritty city smack in the midst of a fierce revival. I was enchanted by the possibilities around me, by the intoxicating presence of creative people, by actually affordable rents, by the offers to collaborate, by pop-up projects such as an Asian night market or Beckett performances in a former gasholder building. This was the kind of urban community I wanted to be a part of. At their best, small cities offer a blueprint for innovative, inclusive and approachable design.

But small cities are also incredibly vulnerable in times of upheaval. Like many small-business owners, Mr. Christopher had to pivot hard during COVID. In the early days he furloughed most of his staff, and developed a contactless delivery and pickup business model on the fly. He was forced to close a fine dining restaurant, Peck’s Arcade, in favour of the softer profit margins of a pizzeria. Every day was an adventure.

The strip of Broadway outside of Little Pecks where we were sitting had now become an outdoor dining oasis. Planters and bistro lights and umbrellas from six restaurants and bars occupied the spaces where parked cars once stood. A street filled with people is a completely different ecosystem than one lined with private cars – the landscape is softer, safer, slower, blessed with more possibilities. It is a place you want to be.

I asked Mr. Christopher if he thought this revolutionized streetscape was here to stay.

“I think so,” he said. “I hope so.” That familiar alchemy of small-city optimism and uncertainty lingered in the air. He wiped down our table and excused himself; he was off to meet another serial entrepreneur, Cory Nelson, owner of the kitchen incubator space, Albany Kitchen, that offers chefs a chance to test run their concept in a food court kiosk before making the leap to a bricks-and-mortar space.

Mr. Nelson’s kitchen incubators are part of a larger trend in ground floor spaces that are moving away from traditional models of retail, with a single tenant and a long-term lease, where the entire draw is based on the purchasing of goods. The rise of Amazon and e-commerce has cut significantly into the small city’s retail scene, particularly during COVID, and so businesses have had to increasingly develop services that you can’t buy online and occupancy arrangements that allow for flexibility and resilience in the face of current and unforeseen future challenges.

“We’re seeing a lot of maker spaces, stackable retail, pop-up shops, ‘third spaces’ that are increasingly challenging that traditional mold,” Matthew Wagner of Main Street America, a national organization that studies the revitalization of older commercial corridors, told me recently. “The new Main Street is being designed around community-based experience.”

Forty miles south of Troy, the small city of Hudson, population 6,000, was once a bustling factory town and, for better or worse, the site of a world-famous gambling and prostitution scene along what is now Columbia Street. Like Troy, Hudson was gutted by the great manufacturing jobs exodus, but after losing more than half of its population, the city has since transitioned, unevenly at times, into an antiques mecca and creative enclave for displaced Brooklynites. As with many of these small cities, questions of equity and gentrification abound – just a block off the instagrammable vanity boutiques of Warren Street, you will find vacant houses and marginalized communities.

The city, which lacks a formal planning department, struggled to meet the countless civic and social challenges posed by the pandemic, and so an ad-hoc collective of citizens, cultural organizations and architects came together to try to design an equitable shared street plan for Warren Street. Their plan to increase public space, access, and the flexibility of streetscapes proved so popular it was eventually officially adopted by the city.

Troy and Hudson are not alone in their continuing metamorphosis: The pandemic has forced small cities everywhere to reconsider the composition of their downtowns and how space is privileged along their Main Streets. Suddenly everyone is participating in a kind of urban planning revolution. Cities are debating ordinances that allow for permanent outdoor dining areas; impromptu parklets have blossomed; vacant lots have become music venues; sidewalk murals spill forth from storefronts, addressing everything from supporting small business to celebrating frontline workers to Black Lives Matter. Along with this transition comes complex questions of access: Who are these Main Streets for? Do you have to be a paying customer? And are cities quietly turning people away from their Main Street spaces with the kind of storefronts they are encouraging?

Main Street in Vancouver.Jennifer Roberts/Globe and Mail

These questions are not new. The United States – more than other countries, including Canada – has always had a complicated relationship with the symbology of its Main Streets, that often-eulogized patch of American landscape that greets visitors at Disney World. Main Street is not just a place – it is a mindset, an economic and cultural shorthand, a state of nostalgia for simpler times when a sense of community was deeply entangled with a row of shops.

Main Streets are a tricky cocktail of commerce, transportation and social theater, all held in a kind of delicate balance that shifts with the times. As Mindy Fullilove, MD points out in her book Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All, “[Unlike malls], Main Streets are civic spaces, belonging to ‘we the people.’ ” It is that civic space, open to all, that urbanist Jane Jacobs heralded when she talked about sidewalks as “a web of public respect and trust” in her urbanist classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities. According to Ms. Jacobs, shopkeepers, among other duties, are “public characters” who maintain “eyes on the street” and informally mediate this public trust that permeates through layers of “sidewalk contact.”

In large cities, the kind of rich, layered sidewalk contact may arise more naturally, but in smaller cities, a culture of inclusive, vibrant sidewalks must be purposely nurtured, particularly since many of their downtowns are only a few square blocks. Yet the pro-active cultivation of walkable landscapes, of sidewalk density, of Main Street as a civic commons has not always been the agenda in our cities.

Perhaps the darkest time for small-city Main Streets came during the infamous period of Urban Renewal in the sixties and seventies, which sought to address perceived problems of “downtown blight” by ripping out entire city blocks and replacing them with suburban-style shopping malls and parking lots. If the city was broken, the thinking went, let us embrace the car and make our cities more like suburbs.

In small cities, such projects often went through the process of demolition without reconstruction when the project would run out of money or a mayoral office would turn over. Walk the thoroughfares of most small legacy cities and you will still see numerous vacant lots as enduring evidence of this failed period of planning. Such ruptures do untold damage to a Main Street corridor, which, as Dr. Fullilove points out, relies both on its morphology as a “box” – a walled-in, compact civic stage, and a “line” – a cohesive, connective pathway that runs from one place to another. If either of these forms is disrupted, the Main Street begins to suffer.

Broadway in Kingston, N.Y., as it looked in 1906.U.S. Library of Congress

We can see evidence of this further downstream the Hudson River in the small city of Kingston, N.Y. (population 23,000), which has seen its share of tumultuous forces wreak havoc with the boxes and lines of its urban footprint. Originally New York State’s first capital, Kingston was burned to the ground in 1777 by vindictive British troops still salty over their defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. Over the next 150 years, Kingston would become a major centre in the Hudson River corridor for brickworks, cement production and ice making. Fuelled by waves of immigrants, the Midtown factory district along Broadway became a regional hub for garment and textile manufacturing, with at the time state-of-the-art buildings such as the Kingston Knitting Mills, Manhattan Shirt Factory and United States Lace Curtain Mill.

But in the latter half of the 20th century, as these industries waned and the city’s population declined, the region attempted to pivot and throw its economic development hopes on the nascent technology sector. In the 1950s, IBM built a sprawling, 200-acre industrial park campus just outside of the city; at its height, the facility would employ more than 7,000 workers. This was the boom time for suburbs and strip malls and the precipitous decline of downtowns. The automobile was king and we happily designed our landscapes around it.

Citing the historic Rondout waterfront neighbourhood as a “blighted area,” the city of Kingston gutted the district in the 1960s to make way for a highway and bridge that allowed for easy egress out of the city.

“It was devastating,” said filmmaker and historian Stephen Blauweiss, who directed a film about the project called Lost Rondout. “This was a harmonious, mixed, working class community and then it was gone.” To make matters worse, in 1994 the IBM plant, site of the region’s collective aspirations, closed – taking 12 per cent of Ulster County’s economy along with it.

One of Kingston’s challenges is that it has three distinct, disconnected urban centres: Uptown, Midtown, and the Rondout. Uptown Kingston, also known as the Stockade, is a compact, picturesque district with arcade-covered sidewalks, reminiscent of certain streets you might find in New Orleans. In the past, its compactness has actually been a detriment, as the small urban footprint (barely 2x3 blocks) has tested the question of whether such a diminutive downtown could support a healthy restaurant and storefront ecosystem, particularly when it was in such close proximity to a strip mall (with ample parking) just down the hill. The awkward size of its legacy ground floor spaces, which tended to be long and narrow and not conducive to small, start-up operations, combined with heavily seasonal foot traffic, and an archaic zoning code, seemed to lock Uptown in perpetual state of “waiting to launch.”

But after years of inconsistent business, the district has recently seen a rapid influx of out-of-town investment, including the opening of several boutique hotels, such as the Wes Anderson-esque Hotel Kinsley in a 19th-century bank building, and one of the region’s best independent bookstores, Rough Draft Bar & Books.

Like that oft-used Hemingway quote, development happens “Gradually, then suddenly.” During the pandemic, as panicked New York City residents (of a certain means) turned their sights northwards, there was a wild run on property in Ulster County. Houses in disrepair went for multimillion-dollar cash offers over Zoom. Along with Columbia County, where the city of Hudson is located, Ulster County saw the largest percentage rise in home sales in the entire country.

Kingston Mayor Steve Noble, a Kingstonian native and graduate of SUNY’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, has worked hard since his election in 2016 to transition the city to be both a more sustainable and equitable community. His partner, Julie Noble, is the city’s full-time sustainability co-ordinator, a position that is a rarity in small legacy cities. But the sudden flood of outside speculation and the new threats of rapid gentrification have put Mr. Noble’s office in a tricky position. On the one hand, the new tax revenue is welcomed. “But we’re also waiting to see if these new owners and developers will embrace the inclusive mentality of our city,” he said. “People are a little worried.”

Gentrification can seem like a distant idea until suddenly it is everywhere, particularly as many of these communities have seen decades of disinvestment and population decline and are therefore eager for any development at all. It can be difficult to set down the kind of smart growth guidelines, affordable housing laws, minority-owned business grants, and community support systems necessary at an early stage to encourage development that does not simply lead to unchecked rises in property values and harmful community displacement. As we have seen too often in cities across the continent (Boston, San Francisco, Vancouver, Washington, D.C., Miami, Toronto, Austin, just to name a few), by the time this market cycle has been initiated, it is almost impossible to stop it.

Perhaps in no place is the grand experiment of sustainability, equity and inclusion more evident than in Kingston’s Midtown. Midtown, while geographically central, has none of the compact cohesion of Uptown’s streets. It is instead a series of isolated businesses dotted along the long, high-speed car corridor of Broadway that runs between Uptown and the Rondout.

These kinds of thoroughfares, or “secondary Main Streets,” will be familiar to the small city resident. They are a byproduct of the automobile – often they can be found on feeder state roads that lead into cities, and are marked by absence – a series of gas stations, underpasses, condemned factories and vacant lots eviscerate any kind of box-like containment. Sidewalks are broken or missing altogether – there are limited places for contact and for public characters to keep “eyes on the street.”

For years, Midtown felt like not so much a place to be but a place to move through, preferably quickly. Unless, of course, you lived here. Many of the low-income residents displaced by Rondout’s urban renewal resettled in Midtown. The district features a large African American and growing Latino population, along with embedded systemic issues such as an old, deteriorating housing stock and a lack of access to fresh food. The city has faced a continuing challenge to successfully and humanely develop this corridor while also building a holistic sense of connectivity between its three main districts.

One key building block to cultivating this sustainable connectivity is the creation of the Kingston Greenline, an ambitious 20-mile network of bicycle trails, linear parks, and complete streets that will link both the districts of the city together as well as the city of Kingston to the larger Empire State Bike Trail system. The city, in essence, has taken the bold choice of doubling down on the bicycle as the key to smart, inclusive growth. “We see these urban bike trails as a kind of new Main Street that will encourage local business growth, right by the trail,” Mr. Noble said. “They will be used by everyone.”

The city has also initiated one of its largest public investments in road redesign with its US$7.4-million Broadway Streetscape Project, which will put Broadway on a “road diet,” by shrinking the street to a single lane in each direction, while also creating bike lanes in each direction, widening the sidewalks, and installing 50 bioswales to address stormwater runoff along with hundreds of shade trees and plants.

Recently, I visited Kingston to check on the state of the project. Smells of fresh asphalt still permeated the air. Small saplings trembled in their new sidewalk homes. The bike lanes were under construction, but looked glorious in their protected ampleness. It was early morning; cars were few and far between and so I walked out into the middle of the street and just stood there, trying to take in the new spatial barometer of the corridor. Could such a design intervention solve the endemic problems in a broken Main Street?

I’m not sure. A good street is supposed to feel both contained but also rich with entrances and protected places to stop and talk. Broadway still felt wide and yawning. And yet the longer I stood in the middle of the street, the more I felt the investment in the placeness of the corridor and the quiet privileging of people over cars. The seeds, quite literally, had been planted. The city was saying: this street matters.

A car honked at me to get the hell out of the road. I waved apologetically and retreated back to the sidewalk.

I spent the next hour or two walking, beating the bounds of these new wider sidewalks. Laying my hands on the surfaces of the corridor. The storefronts of Broadway are a rich, kaleidoscopic text, conveying the deep sense of hope and loss, the resilience and the struggle, as the city sees its long journey out of COVID. Midtown’s growing Latino population has been particularly instrumental in re-energizing Broadway’s storefronts, as evidenced by the multiple taquerias that greet you on nearly every block. Many storefronts still sat empty, marked by handwritten notes of apology, evidence of how small businesses often lacked the capacity to pivot during the pandemic to an e-commerce platform or apply for Paycheck Protection Program loans and were simply forced to close for good.

'We're still here,' proclaims a sign outside Kingston eatery Lunch Nightly.Reif Larsen

The storefronts that remained each told a story. Everywhere I saw the kind of flexibility, collaboration and community resilience that is becoming a hallmark of the modern Main Street. There is Anajpati’s Asian Grocery Store that has temporarily become Sultana’s Closet, a used clothing store; there is the beloved restaurant Lunch Nightly, whose hanging wood shingle declared, triumphantly, “We’re still here”; there is Pakt, a Southern Food eatery whose storefront windows has become a bulletin board for anti-racism solidarity; there is the Kingston Pop Museum, a storefront-turned-art-museum that was returning after a year hiatus with a show by artist Paul Heath called “Return to Center”; there is Kingston Radio, a bilingual community radio station; there is the storefront headquarters of New Yorkers for Clean Power, right next to the future home of the Kingston Food Co-op.

Just down the street from the Co-op you can find Tilda’s Kitchen and Community Space, opened by Chris Hewitt, optimistically, during the middle of the pandemic (“My wife calls me optimistakenly,” he laughed.) Tilda’s is also the exchange center for the Hudson Valley Current, a local currency that Mr. Hewitt co-founded along with David McCarthy in 2014. One of the arguments for local small businesses is that they keep US$68 out of every US$100 spent in the local community, versus only US$34 at a big box store. Local currencies are an attempt to keep 100 per cent of that capital in the community. Currently more than 400 members exchange Hudson Valley Currents locally and across the region.

“It’s about stabilizing economies, on a micro scale. But we also knew that it would always be more than a currency. We knew that it would be a community relationship builder,” Mr. Hewitt said. “Keeping money local, strengthening Main Streets, and sharing abundance.”

Tilda’s Kitchen and Community Space in Kingston.Reif Larsen

Sharing abundance also means cultivating an inclusive Main Street. For its part, the city of Kingston and Ulster County has committed to supporting and welcoming more minority and women-owned businesses and homeowners, particularly during the challenging times of COVID. In 2020, Ulster County started “Ulster Equity,” a US$2-million loan program for minority and women-owned businesses, and recently the county received a further US$1-million from the federal CARES Act funding to assist struggling minority-owned businesses coming out of the pandemic. Ulster Savings Bank and Rondout Savings Bank have established a US$100,000 loan fund for BIPOC and female food-system entrepreneurs in collaboration with Martin and Tamika Dunkley of Seasoned Gives, called the Evolution Center.

Such resources are critical to ensuring a welcoming, diverse small business ecosystem. Yet many folks I talked to said the real key to developing Main Streets like Broadway is making sure that residents have access to affordable housing.

“We have a housing crisis in the Hudson Valley, plain and simple,” said Kevin O’Connor, executive director of RUPCO. “Our housing stock is some of the oldest in the Northeast. And there just aren’t enough affordable, healthy homes.”

RUPCO, a 40-year old nonprofit, develops affordable housing projects throughout Ulster County, including the Lace Mill in north Midtown, a retrofitted factory that was transformed into low income housing for artists and multiple gallery and studio spaces. “Each one of these projects gets 100-per-cent occupancy almost instantly,” Mr. O’Connor said.

RUPCO’s newest project is Energy Square, just off Broadway, one of the first mixed-used, net zero, affordable housing buildings in the state. Constructed on the site of a defunct bowling alley, Energy Square includes 57 affordable housing units, including seven reserved for the formerly homeless, a community space, and a green rooftop with pavilion. The building features a state of the art envelope and is powered by a geothermal system and onsite solar array. Residents don’t pay utilities. The mixed-used ground floor space showcases the Center for Creative Education (CCE) and a café.

CCE runs an impressive range of arts classes for local at-risk youth, including an award-winning dance company and percussion ensemble. Like so many organizations, CCE had to pivot during COVID and became focused on simply distributing food to all of its youth participants.

“But being here, in this new building, so visible like this, it’s important for the community,” said Drew Andrews, the centre’s executive director. As if on cue, someone banged on the window and waved. “They’re picking up locally grown food for free. They’re grateful.”

The City of Kingston Land Bank, a non-profit organization, is also forging a pathway to growing affordable housing opportunities by buying and restoring blighted properties and then returning them to income-qualified buyers via a transparent process that supports a larger set of community equity goals. As a model, land banks have taken off in New York State since the NY Land Bank Act was passed in 2012 — there are now 26 land banks across the state.

Initiatives like the Land Bank, the Kingston Greenline and Energy Square are challenging notions that sustainable development is a codeword for investment that caters only to a primarily white, upper-class crowd. Kingston is attempting to prove that neighbourhoods and Main Streets can be both sustainable and inclusive. But the future of Broadway remains unwritten and the spectre of gentrification, already brewing in Uptown, haunts residents like Mr. Andrews, who is working tirelessly to support and empower the underserved community who lives in the neighbourhood currently. Every day remains an adventure in the streetscapes of these small cities in transition.

Troy, past and present: Women work at a shirt factory in the 1900s, and a former downtown jewelry store shows filmstrips from Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho in 2021.U.S. Library of Congress; Reif Larsen

Back in the pop-up exhibit space in Troy, Ms. Agyekum and her RPI classmates were standing outside the empty storefront windows, debating how to use them in the exhibition on waterfronts. Should we fill them with water?” one student asked. We all cackled at the thought.

Since we started redesigning this storefront as an exhibition site and urban room where citizens can engage with questions of their city’s future, I have been fascinated with the possibilities of these ground floor spaces and their unique potential for dialogue with the sidewalk and pedestrian culture.

Our class is not alone in this new wave of urban reimagining. Once the exclusive domain of the retail and service industry, the storefront is now being renegotiated by communities across the continent as potential windows of civic engagement. “Third spaces,” a term coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg, refers to the places between work and home that we gather in to create meaning, share stories and strengthen community. For a long time, ad-hoc third spaces have co-existed uneasily within commercial locations like barbershops or coffeeshops or a McDonalds rather than dedicated community spaces. Yet in an age when many people are turning to increasingly siloed virtual spaces for meaning, perhaps it is time for cities to become more mindful in how they design and program their street-level architecture. Main Streets might be reality’s last stand.

As the RPI students took measurements of the storefront windows, a passerby stopped in the middle of the sidewalk. “What is all this?” he said, curious.

“It’s a class,” Prof. Oatman said by way of explanation. The man nodded, seemingly satisfied, though the answer didn’t quite capture what was going on.

Observing all of this unfold, I wanted to say, “It’s a city.”

Reif Larsen hosts Our Future Main Streets: Flexibility, Inclusion, Experience on Tuesday, Dec. 14 at 11 a.m. (ET). Featured speakers include Steve Noble, the mayor of Kingston, NY, and Rusul Alrubail, executive director of Toronto’s Parkdale Centre for Innovation. Register here to attend.

The audible city

How do we make our cities better? Join The Globe and Mail’s Adrian Lee on the City Space podcast as he explores what communities are doing to live more efficiently and prepare for the effects of climate change.

More reading: The future of cities

In 2020, a Globe and Mail series explored how the COVID-19 pandemic would change city planning, public transit and urban lifestyles for generations to come. Here are some of the highlights.

Promenades reborn: A proposal for ‘Canada’s street’

Bikes, pedestrians and the 15-minute city: How the pandemic is propelling urban revolutions

More public bathrooms, less sprawl, better bylaws: 13 prescriptions from urban innovators

Urban Atlantic advantage: Work-from-home offers Halifax people and wealth, but at a price

How COVID-19 has made Canada’s underhoused and unequal communities impossible to ignore

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.