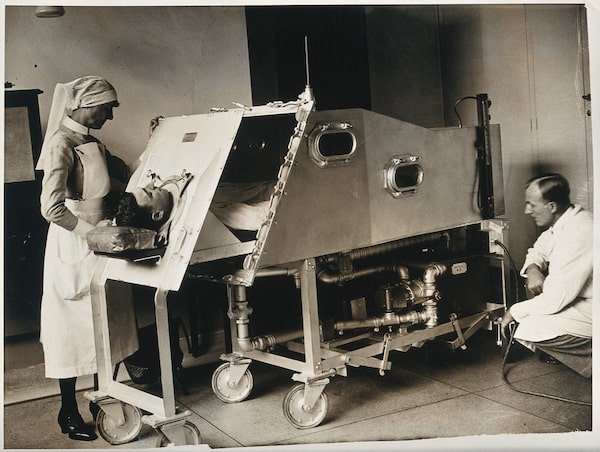

A patient inside an iron lung, St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London, 1930WELLCOME COLLECTION

Lawrence Scanlan is the author or co-author of 24 books on a wide range of subjects. He is writing a series of young adult novels, all of them pandemic-inspired.

“I had a little bird,

its name was Enza,

I opened the window,

and in-flu-Enza.”

– jump-rope rhyme, 1918

The Museum of Health Care, on the grounds of Kingston General Hospital, offers a long view on the history of medicine, and that view can provoke a chain reaction. First comes unease (they did what with that?), and then often, without the initial response ever fading, comes sober second thought.

My first time through the museum, I lingered before two display items: the 19th-century foot-powered dentist’s drill (no thanks!), and the iron lung – the contraption that “modern science” deployed against polio in the 1950s. I was a child that decade, and a cousin of mine spent almost a year in a Kingston hospital with polio, so it was personal, my response to that machine. I am somewhat claustrophobic, and the thought of living inside one was extremely unnerving.

Touring a naval museum in Paris some 20 years ago, I was unsettled by a display – from the days of sail – of surgical tools alongside a letter commending a cabin boy for his bravery while his arm was amputated. For anesthesia, he got as much rum as the sailors could pour down his gullet and a rag to bite on as they held him down. The letter was written by the ship’s surgeon, who was moved by the boy’s courage. Is this a story about crude surgery on the high seas, or is it a story about adolescent pluck? Or both?

The iron lung, likewise, at first struck me as a barbaric device (and it still gives me the willies), but I learned that it was invented by a British scientist in 1670, was first used clinically in 1928, and that a few patients today still live in one. They would die without it. The history of medicine offers so many examples of the light and the dark co-existing.

My first full-time job was in medical journalism, and my interest in medicine has never waned. In 1974, I was halfway through a four-year stint writing for Canadian Family Physician magazine. That year, German Jesuit scholar Ivan Illich first spoke about iatrogenic illness – harm caused by healers. I liked how this thinker rowed against the current. In his book, Medical Nemesis, he argued that “the medical professional practice has become a major threat to health,” causing “more suffering than all accidents from traffic or industry.”

Today, according to the Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, iatrogenesis is the fifth-leading cause of death in the world: Drug reactions and interactions, incorrect drug dosage, infections acquired in hospitals, unnecessary surgery and other mistakes mean preventable deaths. How many? Estimates vary widely but a Johns Hopkins University study in the U.S. put the annual figure there at 250,000. In Canada, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute believes that medical errors account for up to 28,000 deaths annually.

The medical system was already under siege when the coronavirus causing COVID-19 came along. So much about this microscopic invader remains unknown. Does it attack the lungs first, then the brain? Does the body’s immune system go into overdrive – in what clinicians call a “cytokine storm?” (Cytokines are small proteins that facilitate communication between cells.) If the human brain is damaged, is this the work of the virus, or the result of ventilators and powerful drugs – or do the two work in tandem?

Many patients hospitalized with the virus are left with “brain fog,” or what medical specialists call “post-COVID syndrome” – long after initial diagnosis. The symptoms include confusion, lack of focus, short-term memory loss and even psychosis. Distressingly, some patients recover, then relapse.

John Connolly, a neuroscientist at McMaster University in Hamilton, worries that long-term damage from the virus “could be at least as consequential as the health care costs from the pandemic itself.” He cites a British study suggesting that up to 50 per cent of patients hospitalized with the virus will need continuing rehabilitation. Another study, out of China, noted that 76 per cent of COVID-19 patients reported symptoms six months after leaving hospital. Given the surge in nasty variants of the virus and uncertainty over data (the World Health Organization believes that actual cases of the virus may be 20 times higher than the number recorded, which now stands at 132 million), this legacy of the virus is worrisome.

Gordon Boyd, a neurologist and critical care physician in Kingston, calls post-ICU syndrome “a huge health care crisis made worse by the pandemic. Up to 80 per cent of patients in the ICU experience delirium, with scary hallucinations. And up to 35 per cent will have post-traumatic stress syndrome. Half of these patients won’t go back to work.”

Susie Goulding, a floral designer in Oakville, Ont., became ill with COVID-19 symptoms a year ago. She has not yet recovered and cannot work. One of the “long haulers,” she was tested at a private clinic and found to have just 9-per-cent capacity in two key areas of neurocognitive function – working memory and concentration.

She argues that Canada needs many more interdisciplinary clinics to address the mystifying constellation of physical and mental issues facing her and those like her. Britain now has 69 such clinics, but they are hard-pressed to deal with more than one million long-COVID patients. Canada has a dozen clinics but some are focused on research, not rehabilitation, and again, wait lists are extremely long.

In frustration, Ms. Goulding launched a platform last June to share information and resources – COVID Long Haulers Support Group Canada. It now has almost 13,000 members. They say they’re not getting help, that they are Ping-Ponging in slow motion from specialist to specialist, and that some patients are not being believed.

Ms. Goulding agrees with Dr. Connolly and Dr. Boyd that long-lasting effects of the virus will trigger a constellation of physical, psychological and financial repercussions. “It’s going to be a disaster,” she says. “A tsunami.”

Decades from now, some will look back at what was done in the name of medicine and they will shake their heads. The prevailing view for most of the 20th century, for example, was that infants under a year could not feel pain or remember pain. Invasive surgery was inflicted, even on newborns, with only a muscle relaxant given. Doctors believed that anesthesia would harm or kill the infant, and only in the late 1980s did that thinking change. Accepted wisdom is slow to turn.

But not always. War is a bloody nightmare, but war often delivers new insights into tending the wounded. Witness the contributions of Norman Bethune, the Canadian surgeon who saved lives on the battlefield by introducing the mobile blood bank. COVID-19 is just another kind of war, and thanks to those on the front lines and in the research laboratories, physicians will get better at prevention and treating symptoms – even long-standing ones.

When Dr. Boyd looks at medical history, he sees a natural progression of knowledge and practices. But the pandemic, he says, will occupy a special place in that chronicle: “Medical historians will look upon the pandemic as a significant event that changed the way medical discoveries improve the care of patients. Never before have we gone from virus discovery to vaccination programs in a year. Phase 3 trials, involving thousands of patients and testing new therapies, are being published almost weekly. We are learning what works, and what doesn’t, at a pace that can only be described as light-speed.”

This new knowledge comes at a terrible cost to doctors, nurses and other hospital staff, who are at high risk for depression, burnout, suicide – and the virus itself. Some of us owe them our own lives and the lives of those we hold dear.

For all of us, the pandemic has been a source of relentless stress and anxiety. In pre-COVID times, Dr. Boyd played the drums in a seven-member, all-physician rock band called Old Docs, New Tricks. For the time being, he practises alone. “Drumming,” he says, “is a huge stress reliever.”

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.