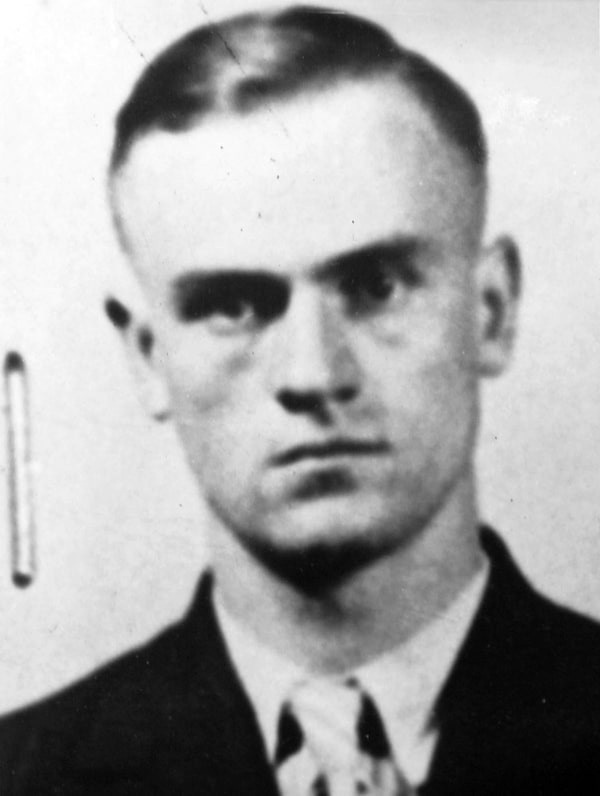

Igor Gouzenko, left, the former Russian code clerk who revealed a Soviet spy ring operating in Canada at the end of the Second World War, is shown during an interview on April 27, 1954.The Associated Press

Scott Anderson’s latest book is The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War – a Tragedy in Three Acts.

In August, the U.S. Senate select committee on intelligence released a 1,300-page report on the involvement of Russian intelligence agencies with the 2016 Donald Trump presidential campaign, characterizing it as an “aggressive, multifaceted effort to influence, or attempt to influence, the outcome of the 2016 presidential election.” In particular, the report focused on the close working relationship between Paul Manafort, Mr. Trump’s campaign manager, and a Russian intelligence operative named Konstantin Kilimnik. It also detailed Russian intelligence contacts with Trump family members, notably Donald Trump Jr. and Jared Kushner, who hoped to gain information damaging to Hillary Clinton, as well as with Trump confidante Michael Flynn. Not surprisingly, Mr. Trump denounced the report as “a hoax” (never mind that it was authored by a Republican-controlled committee), while his inner circle of sycophants adopted their usual position on such matters, either staying mum or decrying the committee’s work as a waste of time and money, much ado about nothing.

Some historians say the seminal event of the Cold War was Igor Gouzenko's defection in Ottawa in September 1945 just a few days after the Japanese surrender ending the Second World War.Copy photo by Dave Chan/Handout

But while the Senate report appears destined to have only limited impact, the latest victim of the hyper-partisanship afflicting the American political scene, it also provides a fascinating look at how Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intelligence minions go about infiltrating foreign governments and the methods they use to build out and maintain their espionage networks. What the report doesn’t do is describe anything all that original. Instead, Mr. Putin’s spymasters have simply dusted off an old playbook that dates back to the heyday of the Soviet Union. The Western world was given its first glimpse of that playbook here in Canada on Sept. 5, 1945, exactly 75 years ago, in an incident that many historians point to as the start of the Cold War.

The protagonist of that drama was a rather unlikely one, a 26-year-old ciphers clerk at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa named Igor Gouzenko. Belying his lowly status, across Mr. Gouzenko’s desk passed an unending stream of top-secret documents to be encoded and sent on to Moscow, along with a corresponding stream in reverse. Probably no other embassy employee had access to such a trove of official secrets, but on Sept. 5, just three days after the formal end of the Second World War, the young clerk called it quits. On that night, he walked out of the embassy with 109 documents hidden under his coat, with the intention of revealing to the Western world the complex network of spy rings the Soviets were operating on Canadian soil. Despite a comedy of errors – coming from a society where all media was state-controlled, Mr. Gouzenko first made for the offices of the Ottawa Journal – and a couple of close calls with NKVD agents hot on his trail, the would-be defector finally gained the attention of Canadian authorities. For their own protection, Mr. Gouzenko and his family were placed under RCMP guard and whisked to an isolated military base outside of Toronto.

Communist Member of Parliament Fred Rose (photo dated c. 1942-1948) was arrested for spying for the Soviet Union on March 14, 1946.Library and Archives Canada

Over the next several weeks, Canadian, British and U.S. intelligence officers pored through the Gouzenko papers and came to a shocking realization: Even while its Western allies had provided the Soviet Union with a flood of vital food supplies and war materiel to sustain their wartime partnership against Nazi Germany, Soviet intelligence agencies had run a host of spy chains targeting those same allies on myriad fronts. Unravelling the chains in Canada yielded up 39 Canadian citizens, including Fred Rose, a communist member of Parliament, as well as Sam Carr, a leader of the Communist Party of Canada. Undoubtedly the most damaging spy uncovered by the Gouzenko papers was a British physicist named Alan Nunn May, who had worked on the Allied atomic bomb program known as the Manhattan Project. As would eventually be revealed, Dr. May passed along critical details of the project to the Soviets, greatly aiding their own atomic weapons research.

But the Gouzenko case also cast a spotlight on precisely how the Soviets went about building and maintaining their spy rings. To see how that worked – and how it correlates to the Russian government’s collaboration efforts with the Trump campaign in 2016 – it’s especially instructive to look at the small fish caught up in the Canadian government’s 1945-46 dragnet.

Nearly all of these lesser fish, some two dozen in all, were mid-level government officials as well as members of the Communist Party of Canada. As true believers, they were quite willing – flattered even – when approached by senior members of the party and asked to do some small favours for their Soviet brethren. Surely most didn’t see their involvement as treasonous; the Soviets were wartime allies, after all, and it was they who were bearing the lion’s share of the fighting and dying against the hated fascists.

U.S. President Donald Trump meets with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki on July 16, 2018.DOUG MILLS/The New York Times News Service

Also helping forestall any potential qualms was the innocuousness of much of the information being passed along, some of it dealing with obscure matters of scant interest to the Soviets, or easily obtainable from open sources. In light of this, what possible harm could there be in providing it to an allied government?

There was also the curious matter of money. For officials of an avowedly anti-capitalist system, the Soviet handlers of the various Canadian spy chains had something of an obsession with seeing that their agents receive some recompense for their labours. Time and again, the spies politely rebuffed these offers – after all, they were performing these favours out of political belief and solidarity, not for financial gain – to the point where the Soviet handlers had to all but force the money on them. In one case, after repeated refusals, an agent was finally browbeaten into accepting a mere $190, to be divided between him and his three sub-agents. One by one, the agents accepted these tokens of appreciation; considering the paltry sums involved – some took as little as $25 – it probably seemed almost ungracious to continue turning it down.

So inconsequential were the activities of some of these lesser fish, and so clear their lack of evil intent, that only 18 of the 39 arrested were ultimately convicted of any crime, while charges against five were dropped altogether. On that basis, a number of historians have argued that the Gouzenko case was deliberately blown out of proportion by the West for propaganda purposes, that most of those caught up in the government’s dragnet were prosecuted for their political beliefs rather than any actual damage they caused.

Paul Manafort, center, arrives at a court in New York on June 27, 2019.Seth Wenig/The Associated Press

This, however, is to ignore one of the foundational stepping stones in spycraft, a foundation the Gouzenko case put on full display. The simple truth is that spies who pass information to a foreign regime are a notoriously unreliable bunch. Some eventually develop cold feet or, if they originally got into it because they needed money, they want out once their financial troubles are resolved. Even with ideological fellow-travellers, political beliefs often have a way of changing. For a spy agency, how to keep their fickle assets on the hook? In a Soviet word, kompromat or, in its English equivalent, blackmail.

What the lesser fish in the Gouzenko case surely didn’t grasp at the outset was that, by their own hand, they had become compromised, that once they handed over any information or accepted any amount of money, they were now essentially bought and paid for by their NKVD handlers, forever blackmailable should those handlers want something more from them in the future. Some, of course, would leave government service or remain in lower-level positions where they would be of little continuing use to their control officers – and these would be the lucky ones. For those who rose to positions of prominence, who gained access to the upper corridors of power and important state secrets, there would be no escape. If some of the information passed to the Soviets in the Gouzenko case was inconsequential, that was far less indicative of the benign nature of the operation than of it still being early days in the spy chains the Soviets were developing.

Kevin Downing, right, lawyer for former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, arrives at the U.S. District Court in Washington, DC on March 13, 2019.MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

Fast forward to the Trump campaign of 2016, and the gift placed in the Russians’ lap. Where in 1945, the Soviets had to largely depend on fellow-travellers for their espionage startups, in 2016 the Russians possessed a far more reliable lure to bring in their marks: the quest for personal power. This also meant that rather than embark on a recruitment drive, always a risky proposition for spy agencies, the marks would willingly flock to them. The first to do so, by most all accounts, was Mr. Trump’s campaign manager, Paul Manafort, with his close link to the Soviet intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik. From there, the Russian influence operation swiftly found new willing accomplices. In an effort to obtain e-mails and documents damaging to Ms. Clinton’s campaign, Mr. Trump’s old friend, Roger Stone, reached out to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, as well as to Guccifer 2.0, a website front actually manned by Russian military intelligence. When another Russian intelligence operative approached Mr. Trump Jr. with the promise of damaging information on Ms. Clinton, the GOP candidate’s son leapt at the chance to arrange a meeting. Joining Mr. Trump Jr. at that infamous Trump Tower conclave were Mr. Manafort and two more of Donald Trump’s closest aides, son-in-law Mr. Kushner and security adviser Mr. Flynn. By their own actions, then, and very much in keeping with the tradition of those ensnared in the Gouzenko case, all of these men were now beholden to Russian intelligence and, thus, blackmailable.

Michael Flynn, Trump's former national security adviser, leaves the federal court following a status conference in Washington on Sept. 10, 2019.Manuel Balce Ceneta/The Associated Press

Little wonder that the Champagne flowed freely in Moscow when Mr. Trump actually won the 2016 election – but even gladder tidings were soon to follow. In the run-up to Mr. Trump’s inauguration, Mr. Flynn, already designated to be the next national security adviser, carried on a secret dialogue with the Russian ambassador, and then lied about it to the FBI. Russian intelligence chiefs must have pinched themselves with gleeful disbelief at Mr. Flynn’s stupidity, for they now had the ability to blackmail the national security adviser to the President of the United States. When it comes to kompromat, it simply doesn’t get any better than that.

Or does it? While the good times promised by Mr. Flynn were over before they even started – having wiretapped the Russian ambassador’s phone, U.S. intelligence officials were quickly cued to Mr. Flynn’s deceit and compelled Mr. Trump to fire him – many believe the Russians long ago amassed kompromat on the most prized target of all: Mr. Trump himself. Only time and future investigations will reveal precisely why the U.S. President has been so obsequiously acquiescent to Mr. Putin over these past four years, but if the darkest suspicions of many in the Western intelligence community are realized, it is likely that the clues were out there all along, in an old playbook that fell into Canadian hands 75 years ago.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.