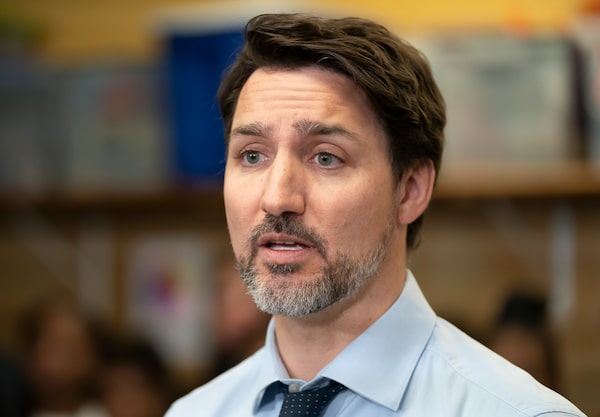

The government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, seen here on March 5, 2020, has continually sent mixed signals to the bureaucracy about how seriously it takes its own promises.Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press

One of the great ironies of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government is that it has proved so ineffective in the one area where it so emphatically promised to outdo its predecessors.

It was always presumptuous on the part of Mr. Trudeau and his former principal secretary, Gerald Butts, to suggest they would run a more effective government than any of those that came before them. But by dropping the ball so spectacularly on so many key files, Mr. Trudeau’s Prime Minister’s Office set itself up for the failure that has now befallen it.

There were self-satisfied chuckles of schadenfreude across the civil service this week as Mr. Trudeau announced the departure of Matthew Mendelsohn as the deputy secretary to the federal cabinet heading up the government’s “results and delivery” unit. With Mr. Mendelsohn’s return to academia, the Trudeau government’s much-hyped experiment in “deliverology” has ended in a whimper.

Mr. Trudeau thanked Mr. Mendelsohn for his “service to Canadians,” but cited not a single accomplishment made by the results and delivery unit that he and Mr. Butts had so championed. Nor did he name an immediate successor to Mr. Mendelsohn, a top official in former Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty’s government who is joining Ryerson University in Toronto.

Mr. Mendelsohn, in Twitter posts, tried to put a positive spin on his tenure, insisting that the “new governance, processes and routines we established helped the government overcome implementation obstacles and hit most of the key targets it identified four years ago.”

Still, the Prime Minister’s silence on the successes (or lack thereof) of the unit Mr. Mendelsohn headed contrasted sharply with the hubris that spewed out of the Butts-led PMO in 2015, which promised to revolutionize policy making and implementation in the federal capital.

Mr. Trudeau’s government spent at least $200,000 to pick the brain of Sir Michael Barber, flying the British consultant and “deliverology” guru to cabinet retreats at resorts in New Brunswick, Alberta and Ontario. Sir Michael was handed a mandate from the Privy Council Office to “provide ongoing information, recommendations and advice on a tailored program to guide departments to meet commitments and deliver on priorities.”

Unfortunately, Sir Michael’s services did not come with a money-back guarantee. And in the end, they may have bought only grief for Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Butts, who resigned last year in the wake of the scandal involving alleged pressure from the PMO on former attorney-general Jody Wilson-Raybould to offer SNC-Lavalin a deferred prosecution agreement.

To anyone who has worked in government, the whole concept of “deliverology” smacked of warmed-over administration theory repackaged by former bureaucrats-turned-consultants seeking to monetize their insider knowledge of the public service. And career bureaucrats do not take kindly to know-it-all political appointees telling them how to do their jobs.

The Trudeau PMO “imposed another layer of administration on some public servants. Their departments had been abiding by evaluation and performance policies for more than 40 years,” former Ottawa Citizen reporter Kathryn May wrote last year in Policy Options. “With deliverology, the public service still did all that work, and now they also had to report the progress on all the government’s goals to a ‘delivery unit,’ which, along with ministers and the Prime Minister, monitored and tracked these priorities.”

The Trudeau PMO has never seemed clear on its own priorities. So how could it expect the senior bureaucracy to be clear on them? At both the micro-policy level (electoral reform, balancing the budget by 2019) and macro-policy level (reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, supporting economic growth while fighting climate change), the Trudeau government has continually sent mixed signals to the bureaucracy about how seriously it takes its own promises.

When it has sprung into action, the Trudeau PMO has typically made a mess of it. The SNC-Lavalin affair, which started out with a straightforward move to bring Canadian law on deferred prosecution agreements in line with that of other developed countries, nearly destroyed Mr. Trudeau’s government all because the PMO failed to abide by its own deliverology credo.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the Trudeau government’s most notable successes – the implementation of the Canada Child Benefit and medical aid in dying, and the negotiation of new health-care funding agreements with the provinces – were overseen by low-key ministers who kept their eyes on the ball rather than their Twitter feeds. Social Development Minister Jean- Yves Duclos and Jane Philpott, Mr. Trudeau’s first health minister, were focused on results, not retweets.

Overall, however, execution has proved to be the Achilles heel of this government. It has proved inept at buying fighter planes or fixing the Phoenix pay system. It promised a bigger role for Canada in global affairs but has earned a reputation abroad for being fickle and stingy. The Canada Infrastructure Bank extends its record for overpromising and underdelivering.

Indeed, the scariest words in Canadian English may have become: “I’m from the Trudeau government, and I’m here to help.”

Konrad Yakabuski

Konrad Yakabuski