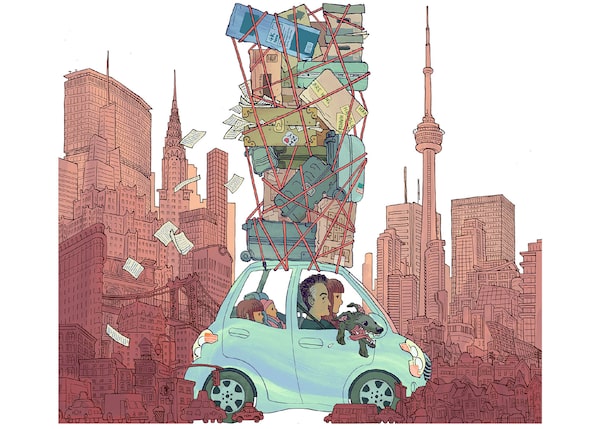

Illustrations by Connor Willumsen

Nathan Englander is the author of five books, including For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. His most recent novel is kaddish.com.

The moment it sinks in we’re moving to Canada, I tell my wife I want to be buried on American soil. It’s Rachel’s job we’re moving for and I figure that grants me a couple of personal requests. While I give her a chance to ponder, I google how far it is from Toronto to Buffalo, and then to Detroit, the nearest major American cities I know.

When I watch our daughter Olivia disappear into her Brooklyn daycare the next morning, I feel a rush of panic over sending her to a Canadian school. What will they teach her up there?

I think, “She won’t know American history.” Then I think, “I don’t know American history.” To test that, I literally ask myself: Who was the second president of the United States?

And honestly, I’m even surprised when I can’t answer something that basic. I mean, I work at a real university! I spend all day sitting around thinking and writing books! But, no, I really don’t have a clue. And admitting that fills me with a sense of a calm. Olivia won’t need to know American history either. Let her learn Canadian history instead. If I teach her George Washington, and the Brooklyn Bridge, and tell her the Mets won in 1969, she’ll basically be caught up to me.

Riding that wave of relief, I let go of a bunch of other move-related concerns. When I look at the overloaded bookshelves in our apartment, and picture the boxes we have in storage, and flash back through all the apartments I’ve lived in over the years, all the dishes I’ve wrapped and unwrapped, the idea of moving again after getting settled, well, I even ditch my initial stipulation. I really am good with dying in Toronto. I tell Rach she can sprinkle my ashes in Lake Ontario and let the currents decide in which country I end up.

As we get closer to leaving, there’s a lot more cheering about our exit than I’d expected. I try not to take it personally. When I tell the woman on the phone at my internet provider that we’re cancelling service to move to Canada, she says, “Congratulations!” as if we’d won the lottery. Even our close friends, all of them New York-loving and Brooklyn-obsessed say, “You’re getting out? That’s the dream.” The fact that the destination is Canada only gets them more excited. It’s all we’d darkly joked about those last years, in our ironical regional left-leaning way. I mean, this was the summer of 2019. If you happened to believe in democracy, or racial justice, or women’s rights, or global warming, or gun control, or about a million other things that you could just file either under “basic human kindness” or “the rule of law” then heading to Canada was a punch line that always killed.

We rush to take a family scouting trip to Toronto, because another thing about that summer is that Rach is around five-hundred months pregnant with (spoiler alert) baby Sam, and we need to get up north and figure out some things while she can still fly. We visit Toronto hoping to get a better picture of the place, to try to imagine school for Olivia and find a neighbourhood that’s in range of the university where Rach will be teaching (back in the days before we’d ever envisioned her teaching on screen).

My vote is that we live near the store that says “Appetizing” in the window. That is, appetizing as noun, like they mean it at Barney Greengrass and Russ & Daughters. I feel safer living within easy access to bagels and lox.

We crisscross Queen and King and Danforth and Dupont, trying to decode the city and saying things like, “If Madison, Wisconsin, had a kid with Red Hook, Brooklyn, that baby would be Roncesvalles.” Or, “The Annex is like Park Slope, if the brownstones were semi-detached and Paul Auster was Margaret Atwood.”

Our friend Terry volunteers to play tour guide. She picks us up early one morning and offers to take us to Starbucks for coffee – which puts the fear of God into me. What will my new life be? Staring at me in her rearview mirror, she catches my face and takes the hint and drives us to a hole-in-the-wall café beside a tattoo parlor instead. A pierced and inked and earlobe-stretched man sits in the window, I imagine having ambled over from next door. We order coffees and pastries, and, while our order is being prepared, Rach asks the barista where he lives, and what his favourite parts of the city are. He gives us his take. And then he gives us our whole order – on the house. He’d moved to Toronto from Tokyo four years before. He knows what it’s like to be new in a place.

Rach thanks him. And I cry in the coffee shop in front of this superhip Torontonian-via-Tokyo, because he is so kind.

When we finally make our move, while Rach and the kids and the dog and I settle into our new space and our new neighbourhood, while I settle into saying “kids” instead of “kid” now that Sammy is on the team, those sorts of unexpected coffee-shop kindnesses keep coming in too many ways to list.

Really, from the moment I pull up at our house and our new neighbours invite me in to print my parking pass and share their WiFi and offer help in any way they can, we’re made to feel right at home.

But as for actually feeling at home, that’s where I lag behind the rest of the family. Rach has her job here. Sam has his mom – his universe – during that stage when “attachment parenting” doesn’t even begin to touch the glorious extremity of that new baby bond. And Olivia is like me in a lot of ways (we both talk frequently and loudly, for example), but thankfully she’s radically different on the delicate flower front.

She shows up at her first-ever day of big-kid school, in a new country, without knowing a soul. We get to the playground fence on the other side of which the junior kindergarten classes congregate. I load on her knapsack, and Olivia walks right through the gate and doesn’t look back.

So that leaves me and the dog, a neurotic rescue, to find ourselves out of sorts. I think the reason the two of us are the most confused in the family, the most anxious, is because both of our realities are fragile constructs – both of our worlds rest wholly on familiarity and habit. We yearn to sniff our way along our daily routes.

I once talked to an eye doctor who explained how none of our eyes are really perfect matches, and our body just knows how to adjust for that. To tilt the head. To imperceptibly pull focus on one side and balance things out. And he gets people coming in, people who’ve never had issues with their vision, but something seems off, they’re getting headaches, they just can’t see right. And he said it’s often related to some kind of personal trauma or shock to the system. Suddenly the head forgets its proper, reflexive, subconscious tilt, and everything appears out of whack.

It’s kind of like that when you move a writer. Also, I’m too old to make friends.

I’m surprised at how much the idea of a border exacerbates – making this place seem farther away from the States when, in a pinch, I could get in the car and be enjoying the view of Niagara Falls from the American side – from New York State! – in less than two hours. I’m closer to Brooklyn than I was when I lived in Wisconsin or Iowa. Latitudinally, we’re south of Maine and Michigan and Vermont. It’s the other-country of it all, coupled with my Yankee ignorance of Canada, that makes it feel so much more distant.

Also, the ignorance isn’t mutual. During the most critical American election cycle of my life, I’d run into my neighbour as we dragged recycling bins to the curb, and, no joke, he’d say something like, “Did you see Klobuchar’s fourth-quarter numbers? If Warren wants to keep her lead, she better hit harder on Medicare for All – though I bet Biden takes the nomination in the end.” And in response I’d say, “A premier is kind of like a governor, and a province is your version of a state!”

I am trying to learn… Where to mail a letter. Where the cash machines are. The name of a good pediatrician and someone who can watch the dog when we’re away. Also, someone gave Olivia a Canadian trivia pack meant for a five-year-old, which Rach and I promptly stole. Canada has one-fifth of the world’s freshwater, is the second-biggest country, has the longest common border, and on and on. At nights, when the kids sleep, we sit on the couch and quiz each other, getting everything wrong.

It’s a continuation of a process started months before, on my second trip up to Canada that summer, taken alone, after Rach is too pregnant to fly. I make a quick one-day excursion to sign papers, to get keys, to meet all the people that need meeting so we can arrange the things that need arranging for our arrival. I schedule an early flight back, as prescribed by the obstetrician, who thinks it would be a shame if I happen to miss the baby’s birth.

I spend that night at Rach’s aunt and uncle’s, who’d moved to Toronto decades before. Sports-loving family that they are, we watch Game 5 of the NBA Championships, convinced it’s going to be the final game of the series, and the first ever NBA championship for the Raptors, and for Canada. After they win, we’re going to head straight downtown to meet, I guess, the whole rest of the country and join in celebrating the victory, just as Rach’s aunt and uncle had done when the Blue Jays took their first World Series in 1992.

So I watch, and I root. I cheer when my hosts cheer. And as I make a real and concerted effort, my heart shifts. I want that win for the Raptors, my new team, and for Toronto, my new city, strange as that is to say. I try the feelings on for size – both Canadianness and sportiness – and I tell you, there is pride and joy and my shifted-heart swelling in the last seconds as the Raptors take the lead, followed by shock and deflation when the Warriors come back to win the game by a single point. We are devastated. It’s honestly sad.

Trying to be positive and to be cheery, I make some joke about what I’ll do or say when I bump into the Raptors at the airport the next morning when the team flies to the States for Game 6.

When I get to the airport early the next day, it’s quiet and nearly empty as I walk the terminal following the American flag signs toward security. Along with a few other gobsmacked travellers pulling out laptops and stripping off belts, I freeze as, one after the other, entering at intervals as one might in a wedding march, the Raptors make their supertall, just-defeated way toward their charter. Kyle Lowry goes by hooded, and then Kawhi Leonard, minding his lanky business, strolls past me looking humble. The smattering of us, the scanners and scannees, all wanting to show our support, quietly clap them through.

Back in New York for Game 6, back with Rach in our tiny apartment, we get Olivia to bed and gear up to watch. It is a sweet, hopeful experience, as we nervously root for a team, knowing that what we’re nervously rooting for is that next stage of life, a baby a month away, a move two months away, a daughter who will stand at attention and sing O Canada every morning come fall. It brings back that two-worlds confusion I remember from all my years living in Jerusalem, when I’d go into a movie theatre and watch everyone on screen running around New York, and I’d dissociate until the lights went on and I’d again find myself around the world – and at home. Curled on the couch, we watch, and we holler, ecstatic, when the Raptors win. A muted cheer rings out on the corner of Washington and Greene.

We stay put when it’s done and watch the Raptors celebrate, a victory for their team, for their city and their country, a championship delivered by a roster on which only Chris Boucher, born in Saint Lucia, holds Canadian citizenship.

As they put words to emotions, as they try to absorb what they’ve just accomplished, live on TV, Mr. Lowry offers his response. With the trophy gleaming at his side, that favourite son – born and raised in North Philly – looks into the camera, into all our Northern eyes, and says, “Toronto! Canada! We brought it home, baby. We brought it home.”

In Toronto, I try to find some hobby to anchor me. This isn’t my first time at the new city rodeo. I know, as does Rachel, how quickly I turn lost, and lonely, and stop shaving, and start wearing the same sweatshirt day in and day out for weeks on end. It’s like some mix of the Unabomber and Oscar the Grouch. Finding a non-writing activity usually helps.

When we moved to Madison for Rach’s PhD studies, I took what we still call “sadness pottery.” Throwing lopsided bowls and too-tiny coffee mugs so helped me get settled that, after I got the hang of it, I’d have stayed sitting at my pottery wheel on the edge of Lake Monona forevermore.

The year we spent on the Zomba plateau in Malawi for her fieldwork was, admittedly, a harder transition, me being used to regular electricity, and being able to call 911 in an emergency, and other perks like that. Still, once I found the one sort-of-functioning dirt tennis court and someone to teach me, I suddenly had my sanity back and, also, something that passes as a backhand by the end.

In Toronto I go with ice skating, which is a skill, like walking, that every able-bodied person here seems to have mastered. I show up at the arena eager for my first group lesson. I look for someone in charge, while admiring the tiny hockey players flying across the ice. I enter the little shop and find a man behind the counter who tells me to go to the locker room and lace up my skates.

Yes, super, that would be lovely, I tell him back. And I ask him for something in a size 9.

He looks confused and I look confused. He asks me if I brought skates for my lesson. And I ask him why I would have – it’s an ice rink, that’s where you trade in your shoes to get them. And I keep searching for a wall of cubbies behind him, one filled with the stinky old sneakers and muddy boots left as collateral. And he, he just shakes his head.

That, in total, is lesson one.

Apparently in Canada you bring your own skates to the neighbourhood rink. I walk outside crestfallen and bump into one of the parents I know from school. I tell her what happened. Without pause she says, “Do you show up at a swimming pool and ask for a bathing suit?” And I immediately understand the degree to which I don’t understand.

What further confuses is the early trips I need to make home – from home. We’re barely in Toronto for a few days when Olivia and I have to fly back to New York for my nephew’s wedding.

I end up waking Olivia hours early to catch a morning flight. We pass through airport security and, at customs, I hand over our passports to the agent and smile very weirdly as I do whenever I face anyone in a position of authority. As my friends have long pointed out, I look like I’m guilty of murder whenever I try to look innocent in any way. The agent thinks I’m guilty, too. He doesn’t wave us through. Instead, he keeps asking me questions about what food I might have. I didn’t think I had any food. And then I remember, I have Olivia’s airport snacks, packed at two in the morning during a period of the day I like to call my “me time.”

I say, “A mozzarella cheese stick,” which doesn’t seem to satisfy. So I put myself back in the kitchen and walk through my own little cheddar-bunny-fuelled memory palace, naming the contents of Olivia’s bento-to-go plastic lunchbox. Then I say, “Ummm, like, three apple slices?” which is apparently what he’s after. He alerts me to the fact that getting caught crossing borders with a segmented apple is a serious crime.

Now he is upset, and, it seems, America is upset. “We expect more of you,” he says. Also, he doesn’t seem to be letting it go.

The problem with the charges as I see them is, I wasn’t caught with anything. I admitted it freely. And Olivia and I hadn’t yet gone anywhere, as the wrong was currently being righted before we’d even passed his desk. Also, if the agent really wants to get into it, had my unwitting mission been successful, we weren’t really crossing a border with that apple at all. For the short journey to New York from Toronto, one passes through U.S. customs on the Canadian end of things. So, what I’m really trying to stress is that Pearson International Airport is mostly in Mississauga but for a sliver of airfield that reaches into Toronto’s western district of Etobicoke. My plan was to feed Olivia those apple slices while she played a game called “Finger Skate” on the germ-covered iPads bolted down to the tables by our gate – tables very much resting atop Canadian soil, on the traditional lands of the Anishinaabe, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, the Huron-Wendat and the Mississaugas of the Credit.

What his desk demarcates is actually a liminal space, a sweet in-between world, a concept my academic wife taught me about, and whose academic appointment is what brought us here. But I don’t say any of that.

At this point, a second officer leads Olivia and me off to another room to face yet another pair of officials, perched behind a different desk. One of the two women asks to be presented with the offending bento box. And the other, donning plastic gloves, unfastens the fasteners, and stares at those slices in their little purple plastic compartment, before lifting them out as you might a condom you found floating in your pumpkin spice latte.

I’m honestly afraid they are going to ban me from entry into the U.S. over this. I’ve been reading articles about random detentions at the U.S.-Canadian border, about five-year bans being given to unsuspecting Canadians for no reason at all, and I wonder, with our heightened Yankee xenophobia, if an American can be banned from America for the crime of transporting a Red Delicious.

That’s when it hits me: If I’m stuck in Canada, where am I stuck – at home or away from home? The question continues to nag after we’re given our passports and what’s left of Olivia’s snacks, and allowed to head on our way.

In New York, Olivia and I check into a hotel in Chelsea, a neighbourhood that had been a central part of my life for more than 30 years. The concierge, looking out at the avenue, says, “The entrance to the High Line is on the next block and–” And I interrupt and say, “Yes, so is the entrance to my shrink’s office,” which I can’t believe comes out of my mouth. But I really feel threatened by the act of being given directions to anywhere in New York. I want her to know that the deli, the deli right over there, is the deli that knows I like my turkey sandwich on a Kaiser roll. And I want to show her in which red brick tower my buddy Pete, from college, grew up. I want her to know that I remember when Tramps played live music and the Limelight was a club, and how amazing it was to show up at Florent for a steak frites at 3 a.m. I want to tell her what the neighbourhood looked like in the nineties, before they built all these hotels, and which businesses were in the storefronts that are other storefronts now. I want her to know that before that High Line was the High Line, two of my best friends fell in love making a movie atop that spur, when it was nothing but weeds and wildflower and broken bottles littering forgotten train tracks.

And that is what I’ve already lost in the few days since leaving. I’ve lost the right to lay claim. It reminds me of all the years when I had long, long hair, a giant nest of curls that are easiest described by asking you to picture Cher, circa Moonstruck, or maybe the drummer from the metal band Ratt. When I cut it off, I swore never to be the middle-aged man, of the infinite middle-aged men, who used to come up to me and, unbidden, say, “I used to have hair like that.”

Right then, I cede ownership. I vow never to answer as I have just answered this nice person, only trying to enhance my visit to New York. I vow never to say, “I used to have a city like this.”

We have our family night, our New York night. We celebrate the commitment being made as the couple stands before a wall of windows beyond which the Hudson River – how much of my life have I spent beside it – rolls by. The night goes late enough for a four-year-old that Olivia, out of nowhere, says, “The problem is, I want to stay at the party, but I also want to go lay down.” And so I lift up my girl and carry her out into the silence. We walk the quiet city streets in our finery, the endless construction sites empty for the evening, the traffic died down, and if there are horns honking or sirens screaming, they don’t register – a perfect peaceful night.

In the morning, already dreaming of getting back to Rach and little Sammy, to my crazy soulmate of a dog, I fly back to Canada with Olivia, the first time ever with the notion of it being a return. We make our way to immigration at the airport in Toronto. We face a Canadian officer who checks our documents and asks us where we’re headed. It’s then, I look to Olivia and think of the new life just begun, and I tell him, “We’re headed home to our family.” Baby, we’re headed home.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BZXL3OG5JVDY3M6FGNTQ2SS7II.jpg)