Illustration by Studio Tipi

Parag Khanna is the author of The Future Is Asian, from which this essay is adapted.

Forecasts of Asia’s rise to global preeminence go back two centuries to Napoleon’s alleged quip about China: “Let her sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world.”

Nearly a century ago, in 1924, the German general Karl Haushofer predicted a coming “Pacific Age.” But Asia is much more than the countries of the Pacific Rim. Geographically, Asia stretches from the Mediterranean and Red seas across two-thirds of the Eurasian continent to the Pacific Ocean, encompassing 53 countries and nearly five billion people – only 1.5 billion of whom are Chinese. The Asian century will thus begin when Asia crystallizes into a whole greater than the sum of its many parts. That process is now under way.

When we look back from 2100 at the date on which the cornerstone of an Asian-led world order began, it will be 2017. In May of that year, 68 countries representing two-thirds of the world’s population and half its GDP gathered in Beijing for the first Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) summit. This gathering of Asian, European and African leaders symbolized the launch of the largest co-ordinated infrastructure-investment plan in human history. Collectively, the assembled governments pledged to spend trillions of dollars in the coming decade to connect the world’s largest population centres in a constellation of commerce and cultural exchange – a new Silk Road era.

The Belt and Road Initiative is the most significant diplomatic project of the 21st century, the equivalent of the mid-20th-century founding of the United Nations and World Bank plus the Marshall Plan all rolled into one. The crucial difference: BRI was conceived in Asia and launched in Asia and will be led by Asians.

Over the past four decades, Asians have gained the greatest share of total global economic growth and Westerners, especially middle-class industrial workers, the least – a trend driven by the rise of manufacturing in Asia. Billions of Asians growing up in the past two decades have experienced geopolitical stability, rapidly expanding prosperity and surging national pride. The world they know is one not of Western dominance but of Asian ascendance.

Asians once again see themselves as the center of the world – and its future. The Asian economic zone – from the Arabian Peninsula and Turkey in the west to Japan and New Zealand in the east, and from Russia in the north to Australia in the south – now represents 50 per cent of global GDP and two-thirds of global economic growth. Of the estimated $30-trillion in middle-class consumption growth estimated between 2015 and 2030, only $1-trillion is expected to come from today’s Western economies. Most of the rest will come from Asia. Asia produces and exports, as well as imports and consumes, more goods than any other region, and Asians trade and invest more with one another than they do with Europe or North America. Asia has several of the world’s largest economies, most of the world’s foreign-exchange reserves, many of the largest banks and industrial and technology companies and most of the world’s biggest armies. Asia also accounts for 60 per cent of the world’s population. It has 10 times as many people as Europe and 12 times as many people as North America. As the world population climbs toward a plateau of around 10 billion people, Asia will forever be home to more people than the rest of the world combined. They are now speaking. Prepare to see the world from the Asian point of view.

The Asia-Pacific is a region of sharp contrasts. At one extreme, it includes the wealthiest country in the world by GDP, Qatar (whose capital, Doha, is shown at left); at the other, it includes Yemen, the fifth poorest country, whose capital of Sanaa (pictured at right) has been a battleground during years of civil war.Associated Press, The New York Times

Asia has the world's most populous country, China, and most populous city, Shanghai (left), with 24.2 million inhabitants. It also has the second least populous nation, tiny Tuvalu, right. Just over 11,000 people live on the cluster of Pacific islands.Reuters, Associated Press

At left, Muscovites brave the snows of Red Square. In terms of land area, Russia is the biggest country on Earth, at 17.1 million square kilometres. Asia also has one of the world's smallest nations, Nauru, right, which is just over 20 square kilometres.AFP/Getty Images, Associated Press

Most people don’t understand what Asia is – even in Asia. Asia’s vastness and range of self-contained civilizations, combined with a recent history dominated by Western or internal concerns, has meant that most Asians today have contrasting views of the parameters of Asia and the extent to which their countries belong to it. Yet, even though Asia is the most heterogeneous region of the world, there is a growing coherence in its dizzying diversity: some psychological underpinning, some aesthetic familiarity, some cultural thread that permeates Asia and differentiates it from other regions.

From kindergartens to military academies, Asia is still mistakenly referred to as a continent even though it is strictly speaking a megaregion stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Red Sea. Asia contains half of the world’s largest countries by land area, including Russia, China, Australia, India and Kazakhstan. Asia also has most of the world’s 20 most populous countries, including China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam. Asia is home to some of the wealthiest countries in the world on a per-capita basis, such as Qatar and Singapore, but also some of the smallest (Maldives, Nauru), least populous (Tuvalu, Palau) and poorest (Afghanistan, Myanmar).

“Asia” is first and foremost a geographic descriptor. We often impose convenient but false geographic labels that suit our biases. In recent decades, Russia, Turkey, Israel and the Caucasus countries have all sought to brand themselves as culturally and diplomatically Western states (and group themselves with Europe at the United Nations). But just because Russians and Australians hail (mostly) from European races does not mean they cannot be Asian. Even through an ethnic lens, Russians and Aussies should be seen – and should see themselves – as white Asians. Many experts hold “Asia” to be synonymous with “Far East.” But Asia cannot be narrowly defined as just China and East Asia. China borders other major Asian subregions, but it does not define them. Hence we should use the term “East Asia” when referring to the Pacific Rim. After all, it is particularly odd for Americans to use the term “Far East” since the region lies to their west across the Pacific Ocean. “East” should therefore be used as a relative directional orientation and “Asia” as a geographic region. Similarly, it remains all too common to use “Middle East” to connote everything from Morocco to Afghanistan, spanning a melange of subregions stretching from North Africa to Central Asia. But North African countries from Egypt westward have little relevance to Asia, even though they are mostly Arab populated. It makes far more sense to refer to West Asia and Southwest Asia to capture Turkey, Iran, the Gulf states and the countries lying between them. Neutral geographic labels are ultimately much more revealing than colonial artifacts.

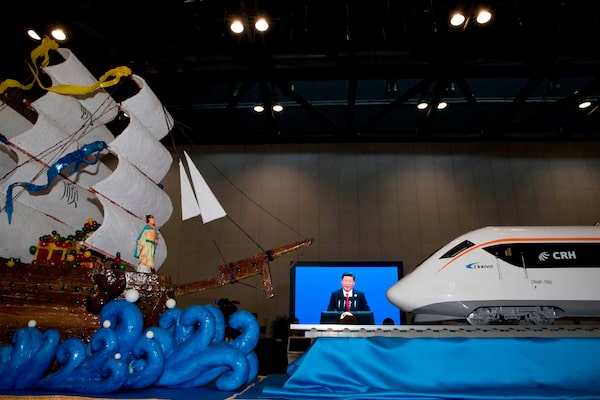

May 14, 2017: A TV screen displays Chinese President Xi Jinping speaking at the opening of the first-ever Belt and Road Forum, a Chinese-led global infrastructure plan connecting Asia, Europe and Africa. The statue at left is of 15th-century Chinese admiral Zheng He; at right is a modern high-speed train.Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press

One key link in the Belt and Road is Sri Lanka, where Chinese investments are paying for a new airport, railway and port. Here, a Chinese tourist takes a selfie with a Sri Lankan friend along Colombo's Galle Face Green oceanfront in 2018.Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

The Colombo Port City project will eventually be the site of tall glass skyscrapers, a busy financial district and a theme park, built on land reclaimed from the Indian Ocean with 65 million cubic metres of sand.Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Despite its vast geography and cultural diversity, Asia is evolving from faint historical and cultural linkages to robust economic interdependence to strategic co-ordination. In 1993, the Japanese scholar and journalist Yoichi Funabashi wrote a prescient essay in Foreign Affairs about the “Asianization of Asia.” He spoke of a new regional consciousness, one not focused on backward-looking anticolonialism but rather pro-actively responding to American Cold War triumphalism and Europe’s single market. Globalized competition, he rightly argued, would require Asia to Asianize, beginning with the “chopsticks” civilizational area encompassing China, Japan, South Korea and Vietnam and eventually reaching beyond to reforming countries such as India. Mr. Funabashi believed that the combination of economic growth, geopolitical stability and technocratic pragmatism would give rise to distinctly Asian ideas about world order.

That time has come. The same ingredients of industrial capitalism, internal stability and search for global markets that propelled Europe’s imperial ascendancy and the United States’ rise to superpower status are converging in Asia. In just the past few years, China has surpassed the United States as the world’s largest economy (in purchasing-power parity) and trading power. India has become the fastest-growing large economy in the world. Southeast Asia receives more foreign investment than both India and China. Asia’s major powers have maintained stability with one another despite their historical tensions. They have formed common institutions such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), ASEAN Regional Forum, East Asian Community (EAC), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – all of which facilitate flows of goods, services, capital and people around the region and will steer trillions of dollars of financing into cross-border commercial corridors. A quarter-century after the United States won the Cold War and led the Asian order, it is now excluded from nearly all of these bodies.

Asia is the most powerful force reshaping world order today. It is establishing an Asia-centric commercial and diplomatic system across the Indian Ocean to Africa, reorienting the economies and strategies of the United States and Europe, and elevating the appeal of Asian political and social norms in societies worldwide.

Vancouver's Chinese New Year parade. Vancouver is now the most Asian city in North America.Rafal Gerszak/The Globe and Mail

Canada already finds itself in a very advanced state of cohabitation with Asian domestic affairs. When it liberalized its immigration policy in the 1970s, it welcomed waves of immigrants from Hong Kong, South Korea, the Philippines and Taiwan, as well as refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Since the 2000s, however, mainland Chinese and Indians have far outstripped other Asians except for Filipinos, while in total, Asians represent more than 50 per cent of all migrants into Canada. Canada has for years offered foreign students a direct path to citizenship, with the countdown beginning the day they set foot on any university campus. Already almost one in every seven Canadians is of Asian heritage.

Vancouver is North America’s most Asian city. In recent years, it has superseded Los Angeles as the top destination in North America for flights outbound from China, with nearly 120 direct flights a week from 10 Chinese cities. At the same time, intra-Chinese rivalries have become part of daily life as the number of immigrants from mainland China has outstripped those from Hong Kong, meaning that “Hongcouver” has lost its Cantonese edge to a new Mandarin-speaking majority.

As if in lockstep with this process, Canadian deportations of Chinese refugees or illegally smuggled migrants have been steadily rising, while undercover Chinese state security operatives have entered Canada to intimidate former employees of state-owned enterprises into repatriating themselves and the funds they’ve allegedly embezzled. Now Ottawa is facing pressure from Beijing to sign an extradition agreement so China can expeditiously haul back economic fugitives and dissidents – in exchange for a free-trade agreement that Canada covets.

Huawei's chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, leaves her Vancouver home to attend a court appearance. U.S. prosecutors want her extradited on fraud charges.DARRYL DYCK/The Canadian Press

More recently, Canada has found itself embroiled in a high-stakes international dispute, caught between the United States – whose Department of Justice wants Canada to extradite Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou – and China, who since Ms. Meng’s arrest has imprisoned multiple Canadian citizens living in China and sentenced a Canadian convicted of drug trafficking to death. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s close ties to Canada’s Sikh community proved embarrassing during his February, 2018, visit to India, where memories of the Sikh separatist movement has not faded. All of this ethnodemographic-diplomatic drama could be just the beginning, given the high-level Canadian government discussions on how to increase the country’s population from the current 35 million to potentially 100 million by the end of the century.

Even if the number of Asian real estate investors, birth mothers and college students coming into the United States and Canada plateaus, the demographic Asianization of North America will continue to a considerable degree. This is generally for the greater good. From San Francisco to Pittsburgh, educated Asians are a key ingredient in what makes some North American cities more cosmopolitan and desirable as places to live in. Vibrant and populous cities with ethnically diverse residents (such as Vancouver and Toronto) rank at the top of the tables when it comes to livability and creativity. Americanization has been a boon for Asians seeking a stable life and liberal education. Now Asianization is breathing vitality into North American communities – and giving North Americans global opportunities they cannot get at home.

May 24, 2016: Justin Trudeau visits the Meiji shrine in Tokyo ahead of a G7 summit in Japan.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Sept. 1, 2016: Mr. Trudeau and his wife, Sophie Gregoire Trudeau, hold their daughter Ella-Grace's hand as they visit a section of the Great Wall of China.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Feb. 21, 2018: The Trudeaus, including son Xavier, visit the Golden Temple in Amritsar.Sean Kilpatrick

Geopolitical forecasters like to identify a neat global pecking order, always asking “Who is No. 1?” But power can’t be measured simply by comparing static metrics. The United States is still the leading global military power with the deepest financial markets and largest energy production. Europe still leads the world in market size, the quality of its democratic institutions and overall living standards. Asia in general, and China in particular, boasts the biggest populations and armies, highest savings rates and largest currency reserves. Each has different types of power, quantities of power and geographies of power. There is no definitive answer to who’s No. 1.

The time has come to approach Asian dynamics from the inside out. The histories and realities of Asians shouldn’t have to be qualified or apologized for. Westerners must be placed, even briefly, in the uncomfortable position of imagining what it’s like when about five billion Asians don’t care what they think and they have to prove their relevance to Asians rather than the reverse.

To see the world from the Asian point of view requires overcoming decades of accumulated – and willfully cultivated – ignorance about Asia. To this day, Asian perspectives are often inflected through Western prisms; they can only add colour to an unshakable conventional Western narrative, but nothing more. Yet the presumption that today’s Western trends are global quickly falls on its face. The “global financial crisis” was not global: Asian growth rates continued to surge, and almost all the world’s fastest-growing economies are in Asia. In 2018, the world’s highest growth rates were reported in India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and Uzbekistan. Although economic stimulus arrangements and ultralow interest rates have been discontinued in the United States and Europe, they continue in Asia. Similarly, Western populist politics from Brexit to Donald Trump haven’t infected Asia, where pragmatic governments are focused on inclusive growth and social cohesion. Americans and Europeans see walls going up, but across Asia they are coming down. Rather than being backward-looking, navel-gazing and pessimistic, billions of Asians are forward-looking, outward-oriented and optimistic.

Nov. 9, 2017: President Xi Jinping of China welcomes his U.S. counterpart, Donald Trump, to Beijing.DAMIR SAGOLJ/Reuters

The most consequential misunderstanding permeating Western thought about Asia is being overly China-centric. Much as geopolitical forecasters have been looking for “No. 1,” many have fallen into the trap of positing a simplistic “G2” of the United States and China competing to lead the world. But neither the world as a whole nor Asia as a region is headed toward a Chinese tianxia, or harmonious global system guided by Chinese Confucian principles. Although China presently wields more power than its neighbors, its population is plateauing and is expected to peak by 2030. Of Asia’s nearly five billion people, 3.5 billion are not Chinese. China’s staggering debt, worrying demographics and crowding of foreign competition out of its domestic market are nudging global attention toward the younger and collectively more populous Asian subregions, whose markets are far more open than China’s to Western goods. The full picture is this: China has only one-third of Asia’s population, less than half of Asia’s GDP, about half of its outward investment and less than half of its inbound investment. Asia is therefore much more than just “China plus.”

Asia’s future is thus much more than whatever China wants. China is historically not a colonial power. Unlike the United States, it is deeply cautious about foreign entanglements. China wants foreign resources and markets, not foreign colonies. Its military forays from the South China Sea to Afghanistan to East Africa are premised on protecting its sprawling global supply lines – but its grand strategy of building global infrastructure is aimed at reducing its dependence on any one foreign supplier (as are its robust alternative energy investments). China’s launching the Belt and Road Initiative doesn’t prove that it will rule Asia, but it does remind us that China’s future, much like its past, is deeply embedded in Asia.

June 10, 2018: The leaders of India, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Pakistan pose for a photo ahead of a meeting of the Shanghai Co-operation Organization in Qingdao, China.Sputnik Photo Agency/Reuters

BRI is widely portrayed in the West as a Chinese hegemonic design, but its paradox is that it is accelerating the modernization and growth of countries much as the United States did with its European and Asian partners during the Cold War. BRI will be instructive in showing everyone, including China, just how quickly colonial logic has expired. By joining BRI, other Asian countries have tacitly recognized China as a global power – but the bar for hegemony is very high. As with U.S. interventions, we should not be too quick to assume that China’s ambitions will succeed unimpeded and that other powers won’t prove sufficiently bold in asserting themselves as well. Nuclear powers India and Russia are on high alert over any Chinese trespassing on their sovereignty and interests, as are regional powers Japan and Australia. Despite spending $50-billion between 2000 and 2016 on infrastructure and humanitarian projects across the region, China has purchased almost no meaningful loyalty. The phrase “China-led Asia” is thus no more acceptable to most Asians than the notion of a “U.S.-led West” is to Europeans.

China has a first-mover advantage in such places where other Asian and Western investors have hesitated to go. But no states are more keenly aware of the potential disadvantages of Chinese neomercantilism than postcolonial countries such as Pakistan and post-Soviet republics such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. They don’t need shrill warnings in Western media to remind them of their immediate history. One by one, many countries are pushing back and renegotiating Chinese projects and debts. Here, then, is a more likely scenario: China’s forays actually modernize and elevate these countries, helping them gain the confidence to resist future encroachment. Furthermore, China’s moves have inspired an infrastructural “arms race,” with India, Japan, Turkey, South Korea and others also making major investments that will enable weaker Asian countries to better connect to one another and counter Chinese maneuvers. Ultimately, China’s position will be not of an Asian or global hegemony but rather of the Eastern anchor of the Asian – and Eurasian – megasystem.

The further one looks into the future, therefore, the more clearly Asia appears to be – as has been the norm for most of its history – a multipolar region with numerous confident civilizations evolving largely independent of Western policies but constructively coexisting with one another. A reawakening of Western confidence and vitality would be very welcome, but it would not blunt Asia’s resurrection. Asia’s rise is structural, not cyclical. There remain pockets of haughty ignorance centered around London and Washington that persist in the belief that Asia will come undone as China’s economy slows or will implode under the strain of nationalist rivalries. These opinions about Asia are irrelevant and inaccurate in equal measure. As Asian countries emulate one another’s successes, they leverage their growing wealth and confidence to extend their influence to all corners of the planet. The Asianization of Asia is just the first step in the Asianization of the world.

A lion dancer walks past a shop selling new year's decorations in the Jakarta's Chinatown. People of Chinese descent in Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim country are preparing to celebrate the lunar new year on Feb. 5 this year.Achmad Ibrahim/The Associated Press

Children learn traditional paper cutting ahead of the new year in Lianyungang, in China's eastern Jiangsu province.STR/AFP/Getty Images

In 2019, the Chinese calendar marks the Year of the Pig. In Taipei, this chef has prepared pig-shaped baozi, or steamed buns, to mark the occasion.SAM YEH/AFP/Getty Images

The legacy of the 19th-century Europeanization and 20th-century Americanization of the world is that most countries have been shaped by the West in some significant way: European colonial borders and administration, U.S. invasions or military assistance, a currency pegged to the U.S. dollar, American software and social media and so forth. Billions of people have acquired personal and psychological connections to the West. They have English or French as a first or second language, have relatives in the United States, Canada or Britain, cheer for an English Premier League football team, never miss films starring their favorite Hollywood actor and follow the ins and outs of U.S. presidential politics.

In the 21st century, Asianization is emerging as the newest sedimentary layer in the geology of global civilization. As with its predecessors, Asianization takes many forms but is universally palpable: selling commodities to China, recruiting software engineers from India, buying oil from Saudi Arabia, taking vacations in Japan or Indonesia, recruiting nurses from the Philippines, hosting construction crews from Korea, doing apprenticeships in the UAE and other relationships. Asian businesspeople strut around the world as their passports gain more visa-free privileges. Singapore and Japan have overtaken Germany in Henley & Partners’ “most powerful passports” index, South Korea also ranks ahead of most European countries and Malaysia has nudged ahead of many European passports as well. A new layer of Asian-ness is creeping into people’s identity and daily life as well. Around the world, students are learning Chinese and Japanese, entrepreneurs are launching businesses in Asian metropolises, travellers are flocking to beaches from Oman to the Philippines, intermarriage is rising among Indians and Thais, youths are converting to Islam, movie theatres are showing Bollywood movies and more.

The Asian way of doing things is spreading. Governments are taking a stronger hand in steering economic priorities. Democratic impulses are being balanced with technocratic guidance. Social discourse in the West not only boasts of rights but speaks of responsibilities. Western officials, businesspeople, journalists, scholars and students are touring Asia to observe how to build large-scale, world-class infrastructure and futuristic cities, study how governments use scenarios and data to align industries and universities, and examine social policies that promote national solidarity. In many ways, rather than “them” aspiring to be like “us,” we now aspire to be like them. The name of the flagship publication of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy aptly captures the transition to this new paradigm: Global-is-Asian.

A child reaches for the tassels of a traditional Chinese lantern at a floral display in Singapore's Gardens by the Bay to mark the upcoming lunar new year.LORIENE PERERA/Reuters

At the same time, becoming more Asian does not necessarily mean becoming less American or European. Asianization is like an additional layer of paint on an already colourful canvas; it adds texture and hues. As the great British historian Arnold Toynbee documented, civilizations do not merely displace each other, discarding rivals’ ideas and substituting their own fully formed ideologies. In this spirit, Asianization borrows much from the past even as it inserts its principles into the world as it already is. Nineteenth-century Europeanization brought with it colonial inclusion in a world economy, modern forms of government administration and exposure to liberal Enlightenment philosophies. These in turn gave rise to nationalism as colonies sought to become independent countries – an idea strongly supported by the United States as it became the world’s leading power. Twentieth-century Americanization ratified democratic self-determination through formal multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, promoted the spread of capitalism and industrialization through global trade and investment treaties, and inspired an appreciation for the great potential of unencumbered freedom. Asianization absorbs but also challenges aspects of these earlier eras. Asians practice neomercantile industrial policy rather than free-market capitalism, with government and business colluding to gain the biggest share of commercial arrangements. Asia is also highly bureaucratized and multilateral, but via new Asian-driven institutions that both complement and compete with incumbent Western ones. Many Asian countries have inherited Western parliamentary systems, but have grafted on more technocratic mechanisms in pursuit of societal welfare. Asianization, then, is not about replacing the past wholesale but about modifying it.

Historical eras are accumulating in ways that do not allow for one model to fully impose itself on the others. Instead, as Asian institutions and norms take their place alongside those of the West, they synthesize into a fusion that itself becomes the global norm. Some aspects of global Westernization will remain central to global life, especially the English language, capitalism, and the pursuit of scientific excellence and technological disruption. But over time, others will fade, such as the appeal of American-style democracy and unsustainable consumerism. The question is not which order will prevail, but rather in which ways is Asia shaping a new global order that encompasses all of us?

We are only in the early phases of Asia penetrating all other civilizations as the West did over the course of centuries. Much as one could not have foreseen the impact of European commercial exploration in Asia or across the Atlantic nor the United States’ entry into the First World War, the outcome of this process is uncertain. As with previous centuries of Europeanization and Americanization, Asianization is a double-edged sword. You may or may not like some (or many) aspects of global Asianization – the same has certainly been true for the billions of people worldwide on the receiving end of Americanization. Nonetheless, it is widely observed that the United States managed to remake the world in its image. Asia is now doing the same. Everyone can articulate how “American” or “European” he or she is. Now we are learning to grasp how “Asian” we are as well. How Asian are you?

Illustration by Studio Tipi