I heard Amy running before I saw her. She dumped my birthday present – which was heavier than I imagined – into my arms. Apparently, I wasn't unwrapping it quickly enough because she began to help me open it.

I wasn't sure at first – all I saw was a stack of hundreds of papers.

She was beaming, as if she'd just given me the greatest gift in all the world. I made out a few words: Pilot. Mutchnik. Will's Apartment.

"No way!" I said, furiously tugging off the remaining gift wrap.

"I went through two ink cartridges," she told me. Every single Will & Grace script. "My mom was so mad! It took, like, all night to print out."

"We have to read these," I said. "Right now!"

"Duh, Poodle," she said, biting her bottom lip. I knew how I should respond.

"Who's your daddy?" I asked.

She pushed forward her chest, looked over her shoulder, and, in her best Karen Walker voice, said, "You are."

Over the next few months, of early 2001, I spent every free second I had reading through the scripts with Amy, one of my best friends in high school, reciting Jack and Karen lines over and over again. The dialogue became almost fused with our own thought processes.

To say that a TV sitcom made me gay is a bold claim, I realize. I'm not saying that Will & Grace turned me gay the same way that the show's characters often accused Grace of turning some of her ex-boyfriends gay, or the same way they accused Jack's or Will's mothers of turning their sons gay. ("Making someone gay is exhausting," Jack said. "I don't know how my mother did it!") It's not as if somehow running Jack/Karen dialogue with Amy rewired the hardware in my pants.

Will & Grace, long before I was even aware of it, suggested that being gay – for me, anyway – was something more than being homosexual, and that even if homosexuality wasn't available to me (for whatever reason), that something more was.

I can sum up that something more in a word: camp.

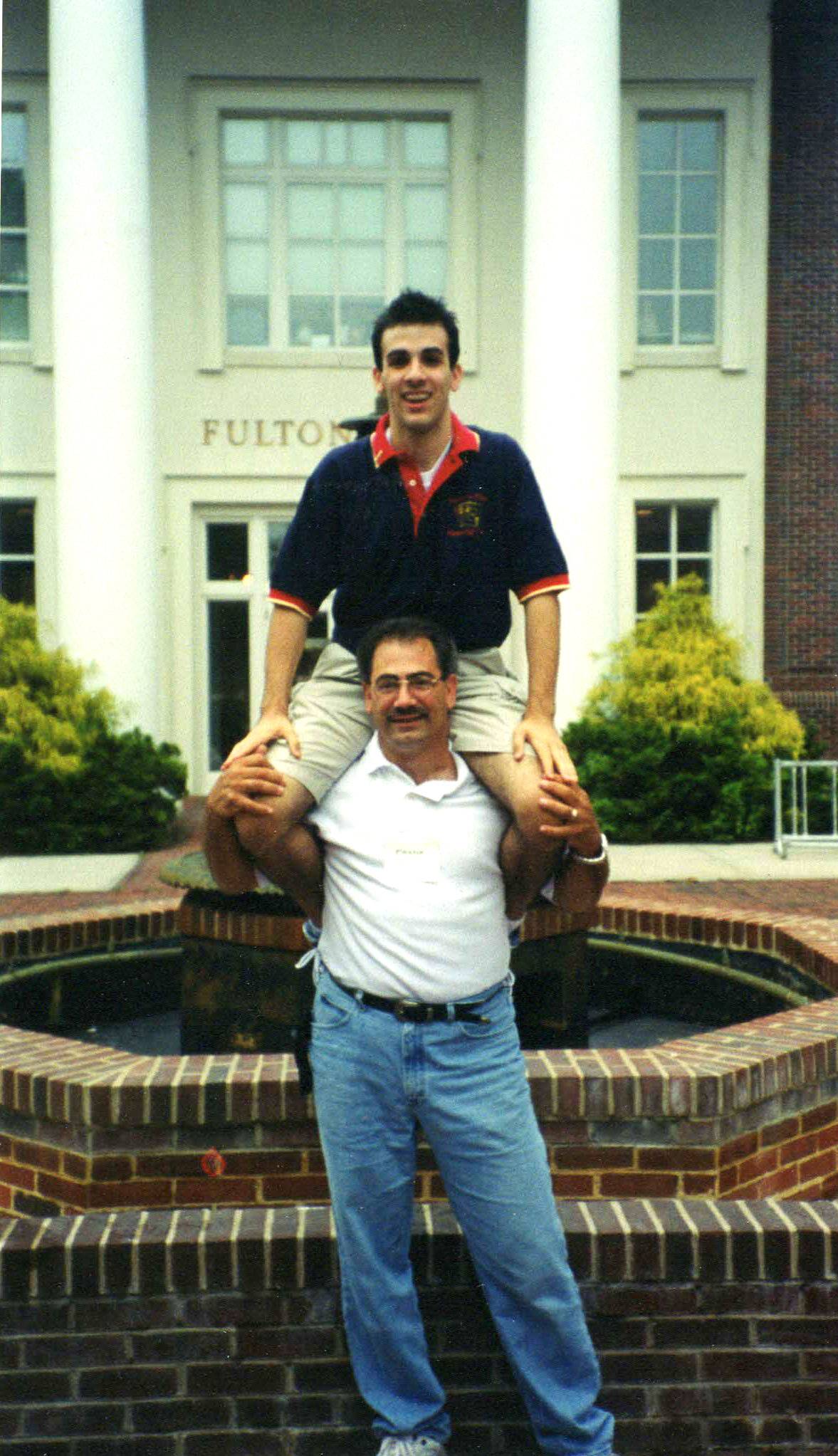

Brandon, right, with his partner Andy on the night he proposed to him.

COURTESY OF BRANDON AMBROSINO

Our favourite scene to perform was the infamous Boob ATM scene. Jack, in need of cash, runs his credit card twice through Karen's cleavage – denied both times. Aha! Wrong slot. So he slides it down her butt crack. "Approved," Karen says, languidly, in a voice that you might otherwise have to pay $2.95 a minute to hear.

I could tell Mary, my girlfriend at the time, wasn't thrilled with the ATM stuff. I thought she might have been concerned that her good, Christian boyfriend was cheating on his good, Christian Mary. Probably more true was that, thanks to Will & Grace, her Good Christian Boyfriend was a Good Christian Mary.

And if she thought that, she was right.

In her seminal Notes on Camp, Susan Sontag defines it as "the love of the exaggerated, the 'off,' of things-being-what-they-are-not." The essential element, she argues, is "a seriousness that fails." Of course, back in high school, I wasn't reading queer theory, but I was watching Will & Grace and learning this same lesson. Everyone around me wanted to be so serious all the time; I learned from the series that I should never allow them that unchecked dignity. In fact, I shouldn't even allow myself that dignity.

In the camp aesthetic that is so emblematic of traditional gay male culture, David Halperin points out in How To Be Gay, the joke is always on the jokester. Will & Grace embraces this rule: Will has no will; Grace is graceless; Karen couldn't care less; and Jack is anything but "Just Jack" – in cheese terms, he's smoked gouda with a trick jaw, as he once put it.

Will & Grace made me gay because, long before I stepped foot in a gay bar, or embraced homosexuality, the show taught me how to camp about things, how to not take things seriously – how to not take them straight.

I found heterosexuality everywhere I looked – especially when I looked at my girlfriend – and the best way to engage it was to throw a spoke in the wheel of its self-seriousness, a strategy I learned from Jack.

"Hey!" he yells at a making out Grace and Nathan. "What you two do behind closed doors is your business, okay, but flaunting that lifestyle like you're doing right now is just plain ge-ross."

Because of our demanding performance schedules – we went to a performing-arts school – Amy and I took to devoting the most time to rehearsal during advanced chemistry (a class which, to this day, I'm not sure how I was ever signed into). We sat in the very first row, just in front of our teacher's desk, and ran our lines while our teacher wrote chemistry kinds of things on the blackboard. Neither we nor Dr. U had any qualms about talking over the other party. Dr. U often acted annoyed with us, and she may have arguably had small reason for it. Once, for example, we both showed up to lab in flip flops, and our teacher said we couldn't participate in the experiment because something about our toes getting burned off. Rather than take a zero, we had a better idea: We'd conduct the experiment in our tap shoes, which were always somehow readily available. Such choreographic preparation has been one key to my continued success.

We knew Dr. U wasn't impressed with our hoofing, but we never thought she had a problem with our Will & Grace performances because she never addressed us about them. It wasn't until my mom asked why I got a D in chemistry that I realized our teacher must have hated the show.

She wasn't the only one. My girlfriend's dad made his own disgust with the show readily evident. He was once so angry at a gay joke – Girl to boy: "I'm in love with another man." Boy to girl: "Thank God! Me too!" – that he got up from the couch, shook his head disgustedly, and fled the television set like the Good Baptist he was.

At least Mary liked the show more than her father, which, looking back, probably makes sense, given her romantic attractions. Often VHS reruns would play on the TV next to my bed as we made out and played our own version of the ATM boob game.

My obsession with Will & Grace followed me to Liberty University, the conservative Christian college founded by the late Rev. Falwell, a man who was pivotal in marrying conservative American politics with Evangelical Christianity. Everyone is always interested to know how I ended up the school. Oldest story in the book: Boy follows girl to Christian college. Boy and girl decide to see other boys. Boy has exorcism to get rid of demons of homosexuality. (The exorcism, by the way, took more than five hours. I assume it takes gay demons a long time to leave a body they've moved into because there's just so much designer furniture they have to pack up.)

At Liberty, I found a way of bringing Will & Grace into most of my conversations, especially in-class ones. One of my English teachers had a wardrobe every bit as stylish as Karen Walker's so I immediately knew I could trust her. I told her about the gay stuff – my struggle with homosexuality, as I called it – but she probably would have put it together when I asked if I could write my midterm essay on Will & Grace.

"I don't have a problem with that," she said.

"I didn't think you would, but I wasn't sure because, well, this is Liberty University."

"In fact," she said, "think about the title of the show: Will and Grace – those are very important concepts to the Christian faith."

After she said that, I started watching the series with one eye on religion – and I found it everywhere. There were references to God (Jack: "Is she mad at me?"), jokes about Satan (Karen: "That is the deal, isn't it, Red?"), considerations of Heaven (Jack: "Do they let gays in? No wait, don't tell me, I want to be surprised!"), discussions of Judaism (Grace on Hava Nagila: "It's an ancient Hebrew song about … something Jewish!"). There was an entire episode about a financial arrangement with a nun (played by Ellen DeGeneres), and several episodes featuring other men and women of the cloth. They even had a Season 2 episode, starring Neil Patrick Harris, which tackled ex-gay therapy. "They're trying to make gay people straight," Karen exclaimed. "Good Lord! Don't they know what that'll do to the fall line?"

The gayness that Will & Grace taught me, in other words, was perfectly at home in and compatible with religion, even if its attitude was more ironic than reverent. Perhaps that's one reason why, despite many gay men's prodding, I've never given up on religion: Why would I? It's too much of a hoot! As Sarah, that matriarch of Judaism, once announced, "God has created laughter for me, and all who hear will laugh with me."

Sure, some self-proclaimed religious people think I'm going to Hell or that I'm demon possessed or any one of a number of terrible things about me. But whenever I'm confronted with that kind of idiocy, I just dismiss it with godly laugh and think about a funny exchange from the show.

Jack: "Grace, you're so generous. I swear, if you weren't Jewish, you'd definitely go to heaven."

Grace: "Thanks, Jack. And if you weren't gay, you'd go there too."

Brandon is shown in 2007 when he was 21, recently out and studying at the conservative Christian Liberty University.

COURTESY OF BRANDON AMBROSINO

At some point during my sophomore year of college, I found out about a television writing fellowship program for wannabes, such as me, hoping to break into the biz. (Spoiler alert: still a wannabe, which is why you're reading my zingers here and not hearing Jack McFarland snark them out.) To apply, I wrote a Will & Grace script. The only sitcom writing advice I had to go on was something I'd heard legendary director James Burrows say on one of the DVD featurettes: Make sure the play plays.

My parents read my script before I mailed it off. Around the same time, they discovered why I might have liked the series as much as I did. My mother, as has always been her habit, accidentally found her way into my book bag, and there accidentally discovered a book given to me by my ex-gay therapist called You Don't Have to Be Gay: Hope and Freedom for Males Struggling With Homosexuality or for Those Who Know of Someone Who Is. It isn't a snappy title, for sure, but I suppose the author gave up his wit when he went straight.

"I think we need to have a talk," she told me over the phone. "I was going through your bag – but only to find my car keys, because I thought they were in there – and I found a book … "

As I learned from Will & Grace, the best way to deal with seriousness was to deflate it, so I drained the moment of drama by cutting to the chase. "Oh, the gay book?"

My mother was caught off guard. "Yyyes … that book … and I think you need to come home so we can talk about it."

I was currently in a car with one of my hot straight-but-not-narrow-especially-when-horny college roommates, and I really didn't want to forfeit such a serious non-committed relationship. So I told her I was staying on campus that summer but she shouldn't worry about my struggle with homosexuality because I was seeing two therapists and they knew what they were doing.

"We also wanted to talk to you about your Will & Grace script … " she said.

"Did you love it?" I asked. "Because it's very funny."

"Noooo," she said. "And Daddy didn't love it either. Neither did … " and she literally started naming humourless women from our church who read and hated my script.

My parents were angry and disappointed with their discovery, but they limited their anger, at least at first, to my Will & Grace script. Good Christians that they were, they were terrified that their firstborn son would write a script drenched in sexual puns, penis jokes and the word "bitch." All of those things, according to the church we attended, could cause us to lose our salvation, which meant we could go to hell or be left behind if the rapture happened.

But their terror wasn't actually about a script – the script was just easier to talk about. They weren't worried about their son using the word "bitch" so much as they were worried about him being one. My parents knew something that I quietly knew, something that Amy and Mary quietly knew, something that my Liberty teacher quietly knew: that Will & Grace was, to me, about much more than Will & Grace.

It was about Will and Grace and Brandon.

"Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly," G.K. Chesterton says. The sin of Lucifer was self-seriousness – and it weighed him all the way down to hell. If there was anything that attracted me to Will & Grace, it was that the characters always flew. They had an infinite supply of pixie dust, which enabled them to soar high above everyone else bogged down by the weight of earnestness.

Maybe this explains some of my disappointment with the show's reboot, which, although grounded in its original irreverence, allows itself to be bogged down with a seriousness that the characters would have mocked a decade ago. We can contrast the respective postures by reading the newest pilot, Eleven Years Later, against one of the original show's most political episodes, Star-Spangled Banter.

Let's start with the second one. Will and Grace both decide to vote for a politician solely on the qualification of their identity features: Will is voting for the gay man, Grace is voting for the Jewish woman. By the time they learn their candidates are terrible people, election day is almost over and the two decide they don't deserve to vote because they didn't make an effort to get to know their politicians' politics. But just as a moral threatens to bog down the play, Jack barges in and announces there's a black guy on the ballot, at which point, in true Will & Grace fashion, they quickly forget the important lesson they just learned and run out of their apartment to cast their uneducated vote. The joke is on them.

Contrast that with the current season's opening episode. Will and Grace both end up at Donald Trump's White House – she to redecorate the Oval Office, he to try his romantic luck with a terrible Republican politician. Both characters are ashamed that they other would give up their political principles for money and sex, and try to convince each other of their own moral superiority. Wackiness ensues and they end up in a pillow fight in the Oval Office, as one does. The moral? Our woke, progressive, left-leaning characters aren't above the childishness associated with Mr. Trump. But whereas the old series would've let the punchline be the moral, the new series goes a bit further, giving the last show to a close-up, sans laughter, of a red hat on Mr. Trump's chair containing the slogan "Make America Gay Again." Allowing such sombre self-seriousness to have the final word is the very antithesis of the show's gayness, which means, ironically, this may go down in history as the show's least gay moment ever.

The new Will & Grace does at times betray its own seriousness, of course (Grace using her pussy hat for popcorn; confusing Mexico and El Salvador). But in general, there seems to be a preachiness this time around that was absent the original. Some might argue the political preaching is understandable, even necessary given the current Trump administration. But if I've learned anything from watching Will & Grace, it's that camp comes to the rescue at precisely the most urgent times, when the stakes are the highest.

It's probably unimaginable to many young people today, but this was precisely the genius of gay male culture. Even as they rose up to demand more research funding for AIDS, and effectively wrote the book on how fighting for better treatment is the right of everyone in the medical system, gay men found the strength to laugh: "It's my party and I'll die if I want to" became something of a theme song among those living with the disease, thanks to Robert Patrick's 1987 play Pouf Positive. Some got together launched a magazine called Plagueboy, written by and for HIV-positive men, that featured irreverent articles such as "Sex and the Single T-Cell." A similar publication, Diseased Pariah News, also laughed in the face of HIV, as evidenced by a fictitious back-page ad for AIDS Barbie's Malibu Hospice. "Compliment her on her slim, trim new figure!" boasts a caption beneath the familiar figure of a naked Barbie covered in lesions.

This is camp's political power: Instead of preaching, Dr. Halperin says, it demeans. And it demeans everyone, equally. (Camp doesn't care about Good Twitter People's rule about only punching up.) In this way, Esther Newton argues in Mother Camp, camp is a "strategy for a situation."

The situation I found myself in was growing up in religious heterosexual spaces, and the strategy was to not allow those spaces to become too hallowed. I couldn't destroy those spaces – nobody can – but I can and did undercut them by by depriving them of their claim to seriousness. I learned to throw quotation marks around all the seriousness I encountered, even and especially my own. Just as Jack does. "I once went as Lynda Carter," he said, recalling a childhood Halloween memory, "from the Maybelline commercial. That stuff really works. Kids made fun of me all night. I cried and cried. My mascara never ran!"

"When you make fun of your own pain," Dr. Halperin says, "you anticipate and pre-empt the devaluation of it by others." In other words, when gay men laugh at themselves, they dismantle the entire hierarchy of social worth. This isn't a denial of pain – but its transformation.

And nobody – nobody! – can transform pain into something else like the characters from Will & Grace. After almost 30 years, Jack – so effeminate, according to Will, that blind and deaf people know he's gay – decides it's probably time to come out to his mother. There's a moment immediately after Jack's announcement that the audience isn't sure how Judith is going to respond. And in that moment, Karen camps to the rescue.

"I think you're missing the silver lining here. When you're old and in diapers, a gay son will know how to keep you away from chiffon and backlighting."

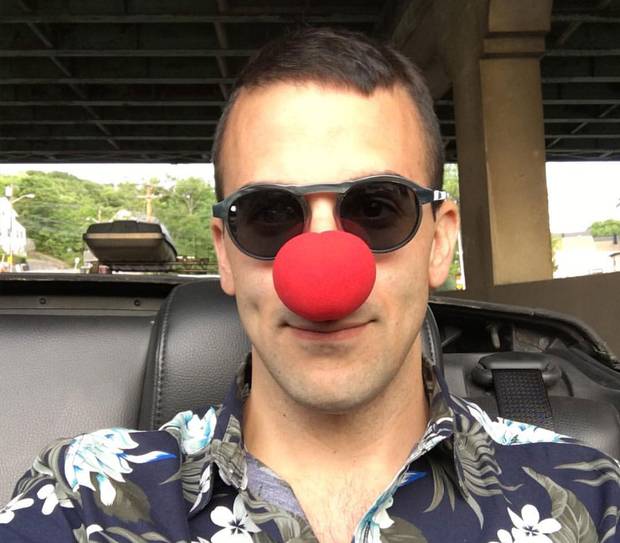

Brandon Ambrosino: ‘I learned to throw quotation marks around all the seriousness I encountered, even and especially my own.’

COURTESY OF BRANDON AMBROSINO

A friend once told me that the difficulty with listening to me speak was that sometimes I referred to characters and situations from Will & Grace as if they were people and events from my real life. So I'd say something like, "That reminds me of the time when Jack… " or, "Remember when Karen said…" But as far as I was concerned, these characters were part of my real life. And I was part of theirs. I was and still am equal parts Will, Grace, Jack and Karen, although most of the time I'm just Jack.

I haven't yet written for a television sitcom, but I have been granted the enviable task of writing my own life. I'm not always sure how best to treat certain plot twists, such as being fired from a Christian theatre for being gay, or having to share a pew at church with someone who has made his anti-gay views quite clear. But no matter what happens on any page of my script, I try my damnedest to make sure my play plays.

It doesn't always work, if only because sometimes the seriousness of the world mangles my comic sensibilities and I'm tempted to respond to the weighty hatred I encounter with a hatred of my own. Of course, such a response only compounds the transgression, and the really necessary thing to do with hatred is to deflate it. Just like Grace's water bra.

"It's always a kiss and a punch with you," Jack complains to Will after he cracks a joke that deflates him.

Always.

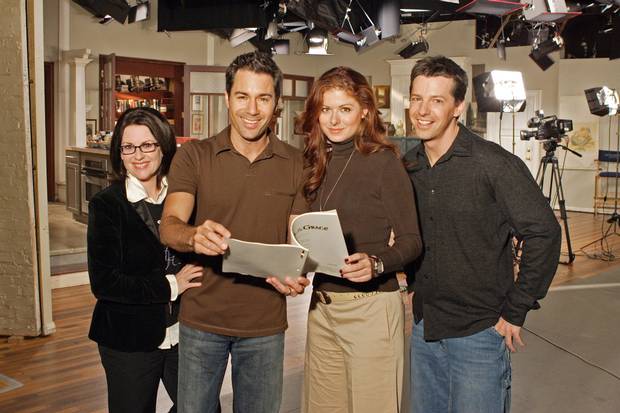

CHRIS HASTON/NBC UNIVERSAL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

QUEER STORIES: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL