As tensions continue to rise between the United States and North Korea over Pyongyang's nuclear weapons and missile programs, this week saw an unusual war of words between the leader of the free world and Kim Jong-un as they traded insults and bragged about the size of their nuclear buttons. At the same time, however, the diplomatic hotline between North and South Korea has reopened and both countries have now agreed to hold official talks on Jan. 9 after two years of diplomatic silence, possibly indicating an opportunity to de-escalate the growing uncertainty on the Korean Peninsula.

Despite mixed signals, some analysts currently estimate the odds of war at 50 per cent. Lieutenant General Wang Hongguang, a prominent retired Chinese general, recently said that "war on the Korean Peninsula might break out any time between now and March."

Everyone acknowledges that war would likely be horrific, so why might it happen?

Generally speaking, there are four pathways to war: states can choose them deliberately on the basis of a cost-benefit calculation; they can stumble into them inadvertently; they can be pushed into them by public opinion; and they can be pulled into them by allies.

Modern history provides tolerably clear examples of each. In the 19th century, Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck twice engineered wars as part of his master plan to unify Germany (the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War, which began in 1870). Through misjudgment, miscalculation, and poor planning, the last Argentine junta stumbled into war with Britain in 1982. Public outrage against Spanish atrocities in Cuba pushed U.S. president William McKinley into war with Spain in 1898. And in 1965, the United States got dragged into the Vietnam War to defend its hapless anti-Communist allies in Saigon.

In the current standoff between North Korea and the United States, we can safely eliminate both the push and pull pathways to war. In neither country is there significant public pressure on leaders to take military action, and since the simmering crisis is essentially a bilateral one, there is no third party to play the role of catalyst. If war breaks out, it will be the result of choice or inadvertence.

No sane North Korean leader would choose war with the United States if one could be avoided. Despite Pyongyang's spectacularly hyperbolic propaganda, North Korea stands no chance today, and would probably have no chance for several years at least, to turn the United States into "a sea of fire." The United States, on the other hand, certainly could "totally destroy" North Korea. No one deliberately chooses a war that they cannot possibly win – unless they believe war is inevitable and prefer to go down in a blaze of glory rather than accept ignominious defeat. It was this mentality that led Cuban president Fidel Castro to urge Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, at the height of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, to use the nuclear weapons he had deployed to Cuba if, as he expected, the Americans were about to invade.

U.S. President Donald Trump, on the other hand, might well decide that military action against North Korea is the least of the available evils, rationally calculating that the costs of inaction outweigh the costs of action. No sane president would conclude this if they believed that Mr. Kim was a containable leader whose only aspiration was to maintain his grip on power. Not every country's nuclear weapons are "totally unacceptable" to the United States (Britain's aren't, for example). So why might Mr. Trump conclude this?

There are two possible reasons.

First, Mr. Kim is clearly not a run-of-the-mill leader. He has assassinated his brother, executed his uncle, and had senior military officers killed by anti-aircraft fire for no more reason than failing to stand up quickly enough when he entered the room or nodding off in a meeting.

Leaders such as Mr. Kim, who are worshipped and glorified over an extended period, tend to begin to think of themselves as infallible and lose the capacity for clear judgment. Adolf Hitler is the classic case. Hitler's delusions of unfailing brilliance ultimately proved to be the Allies' greatest advantage in the Second World War, causing him to stumble from disaster to disaster, beginning with Stalingrad. The cause of these delusions is dopamine saturation. An addictive chemical closely associated with the pleasure response in the human brain, dopamine is produced in abnormally high quantities by absolute power and acts on the prefrontal cortex in such a way as to corrode rational thought.

The fact that Mr. Kim began ruling so young is particular cause for concern. He has already had, and could well have a great deal more, time for Mr. Hitler's God Complex to set into. At some point, Mr. Kim may come to believe that he can succeed where his godlike grandfather failed – in forcibly reunifying Korea under Kim family rule. Were he to go down this path, the result would certainly be war with the United States, and North Korea could by then possess a truly formidable strategic nuclear arsenal.

Notice that Kim Jong-un differs from both his grandfather and his father in his susceptibility to delusions of grandeur. Kim Il-sung was dependent upon, and consciously subservient to, Moscow and Beijing. Kim Jong-il was famously unambitious, content to spend his years in power on basketball, movies and brandy.

If Mr. Kim is a serious long-term threat, now would be the time to nip it in the bud. The most recent North Korean missile test indicates that Mr. Kim is getting perilously close to having the capacity to nuke U.S. cities. If the United States wants to prevent this, there is a rapidly closing window of opportunity.

So far, non-military options have proven impotent. Economic sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and mere threats have had no effect on the scale or pace of North Korea's nuclear weapons and missile programs. It is now abundantly clear that Mr. Kim has no intention of agreeing to denuclearize. He has staked both his cult of personality and his political legitimacy on developing genuine strategic nuclear capability. No leader willingly undermines their own legitimacy.

The second reason why Mr. Trump might consider a nuclear North Korea intolerable is because he is unwilling to be bested in a test of manhood by a thirtysomething North Korean punk. This concern is almost certainly in play to some extent, given Mr. Trump's repeated puerile and transparently Freudian "Mine's Bigger" references to his nuclear arsenal and his "Little Rocket Man" mockery of Mr. Kim.

Could the United States and North Korea stumble into war inadvertently? Normally, countries take mistakes in stride. Accidental intrusions into another's airspace, incidents at sea, and other military missteps normally prompt nothing more than condemnations, demands for apologies, and symbolic expressions of displeasure. Even in the presence of acute tension, these things are relatively easy to deal with, as long as the context is crisis-stable. Crisis stability is inversely proportional to the pressure leaders feel to get in the first blow should war break out, which in turn depends upon their vulnerability to a first strike and their estimate of the advantage to moving first. In a crisis-unstable context, an inadvertent encounter could easily be misread as an opening salvo, triggering a large-scale military response.

The current crisis in Korea is highly unstable. North Korean military plans depend entirely upon moving first. At the moment, the North Korean regime's only hope of survival in the event of war lies in its capacity to inflict so much damage that the United States and its allies will back off and negotiate rather than prolong a conflict. Should Pyongyang decide that a U.S. attack is coming, it will strike south hard and fast. Similarly, Americans know that the only hope of preventing horrendous damage to their allies, and perhaps also to their own troops in the region, is to catch North Korea off guard with a massive blow of their own.

Fortunately, U.S. and North Korean forces have not been in sufficient contact to make inadvertent war highly likely. North Korea has taken no action outside of its borders that might risk accidental conflict, and the United States and South Korea have scrupulously avoided overflying North Korean territory.

This means that, should war break out, it would most likely be the result of a deliberate choice in Washington.

How close is the Trump administration to choosing war? Indications are that Mr. Trump himself is a hawk. We know from his public complaints about the Pentagon's inability to give him plans that he likes that he is actively interested in military options. He has also dismissed negotiations as "pointless" and repeatedly insisted that the North Korean problem "will be solved." Many in Washington believe that Secretary of Defence Jim Mattis and National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster are willing to support military action once it becomes clear that there is no peaceful way of getting North Korea to denuclearize. And U.S. intelligence says that North Korea is close to developing genuine strategic nuclear capability.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson seems to be the primary dove, personally horrified at the prospect of war and evincing much greater willingness than Mr. Trump to give diplomacy a chance. Sources in Washington suggest that Mr. Tillerson asked Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland to co-host the upcoming Jan. 16 meeting on North Korea in Vancouver primarily to be able to tell Mr. Trump that diplomatic efforts are still under way – a delaying tactic, in effect.

Mr. Kim's recent olive branch to South Korea may well indicate that North Koreans, too, are beginning to worry that Mr. Trump might actually choose war. In addition to potentially driving a wedge between Washington and Seoul, the move gives ammunition to those such as Mr. Tillerson who believe that no diplomatic stone should be left unturned. At the very least, Mr. Kim's gambit has almost certainly pushed back the military timetable.

The weapons of war, illustrated

What the North has

April 15, 2017: North Korean special-forces soldiers, wearing night-vision goggles, march in a military parde marking the 105th birth anniversary of North Korea’s founding father, Kim Il-sung. The much-feared North Korean army, trained and configured for offence, might be poorly prepared for an attack without warning by the United States.

DAMIR SAGOLJ/REUTERS

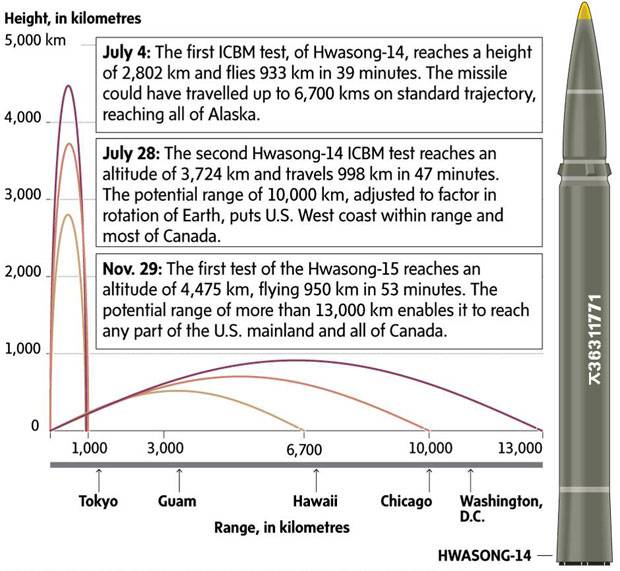

Nov. 29, 2017: North Korea tests the Hwasong-15 missile, which it boasts can reach anywhere in the continental United States (and, by extension, Canada). But it’s unclear whether the missile can carry a nuclear warhead. Below, a comparison of how the Hwasong-15 stacks up against previous missile tests.

KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY/KOREA NEWS SERVICE/ASSOCIATED PRESS

THE GLOBE AND MAIL (SOURCES: GRAPHIC NEWS; UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS, 38 NORTH, CENTER FOR NONPROLIFERATION STUDIES)

What the U.S. has

Oct. 21, 2017: The aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan is escorted into the South Korean port of Busan after completing a joint drill with the South Korean military. Last fall, the South Koreans held joint naval exercises with three carrier groups: the Ronald Reagan, Theodore Roosevelt and Nimitz. In the event of an American first strike on the North, attacks would come as much as possible from naval assets and military bases outside the theatre of operations.

JO JUNG-HO/YONHAP/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Sept. 18, 2017: U.S. Air Force B-1B Lancer bombers fly with F-35B fighter jets and South Korean Air Force F-15K fighter jets during training in Gangwon-do, South Korea. Last month, the U.S. and South Korea held their largest-ever joint aerial drills amid tensions on the Korean Peninsula. If the Americans wanted to attack North Korea first, its first objective would be to bomb the northern side of the demilitarized zone to disrupt the North’s rockets, artillery and tanks.

SOUTH KOREAN DEFENSE MINISTRY

Any general or historian will tell you that nothing goes exactly as planned in war, so it is difficult to forecast with high precision what would happen if war did break out in Korea. But one thing is tolerably certain: a great deal would depend upon who struck first. So let us look at two different scenarios.

In the first scenario, the United States succeeds in landing the first blow. To do this without triggering North Korean pre-emption, it would have to do so from close to a standing start. Wars do not usually begin this way: Normally there are weeks or months of preparations that involve evacuating dependents, prepositioning arms and supplies, and redeploying forces. Sometimes countries prepare for war openly as a deliberate deterrent or compellent signal with an eye toward not having to attack at all (deterrence is the use of threat to prevent something, and compellence the use of threat to get someone to do something). But since there is no prospect of frightening North Korea into denuclearizing, the United States would do everything it could to avoid sounding the alarm.

One way to do this is to prepare for war under the cover of a military exercise. The United States and South Korea routinely conduct joint military exercises, and, predictably, North Korea reacts with hysterical deterrent threats. We do not know how seriously North Korea takes the danger of a surprise attack under the cover of a military exercise, but Pentagon planners would prefer to take no chances and unleash their attack when North Korea's guard was down. So most likely it would take place shortly after a major exercise has concluded. Among other things, this would take advantage of the fact that North Korea has limited capacity to go to repeated alert, or to sustain an alert once mounted. Supplies of fuel are short and must be husbanded for offensive operations, and the country cannot afford to keep military manpower tied up for prolonged periods of time, as keeping the increasingly isolated domestic economy afloat requires soldiers in the fields and factories.

One advantage the United States would enjoy in stealthily preparing for war is that North Korea has little capacity of its own to monitor U.S. military activity. It has no military satellites; it is unlikely to be able to monitor and decrypt U.S. military communications; and its network of spies in South Korea and Japan would have difficulty communicating timely, high-quality warnings even if they could observe and correctly interpret threatening movements. Information asymmetry is one of the biggest advantages the United States enjoys over North Korea. As the 1991 Persian Gulf War illustrated, this can translate into a lopsided outcome on the battlefield.

If North Korea were to receive good-quality early warnings, it would almost certainly have to come from Chinese or Russian sources. This raises an interesting question, particularly for China: If Beijing had information indicating that a U.S. attack on North Korea was imminent, would it better serve Chinese interests to share that information with Pyongyang, or to withhold it? Arguably, if war is to come in any case, China would be better served by a swift North Korean defeat than wholesale destruction in South Korea, its fourth-largest trading partner. (Presumably, the U.S. military has been busy giving China guarantees about U.S. troops not getting too close to the Chinese border in the event of a large-scale conflict.)

The United States' first objective, upon opening fire, would be to suppress North Korea's offensive capabilities. This would entail massive, co-ordinated, extended bombing along the northern side of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to destroy or disrupt North Korea's formidable array of rockets and artillery pieces facing Seoul, bust North Korean bunkers and tunnels, and pin down or destroy North Korean tanks and armoured personnel carriers poised to break south. The first wave of attacks would come from cruise missiles, with later waves coming primarily from long-range bombers (B-1s and B-52s) once North Korea's air defences had been fully suppressed.

The United States would also target every known command post, missile launch site, communications centre, oil depot, and strategic rail junction in the opening hours of operations. As far as possible, attacks would come from naval assets and U.S. military bases outside the theatre of operations, so as to avoid as far as possible putting the South Korean and Japanese governments in a difficult domestic political situation – "as far as possible" here almost certainly not being very far at all, in view of the panic and confusion the outbreak of war would cause in South Korea, and Japanese nervousness about North Korean retaliation.

One would have to assume, of course, that North Korean planners have anticipated much of this and designed around as best they can. In contrast to the first Gulf War, when Saddam Hussein's forces had no plan to defend against a multinational attack to redeem Kuwait, no one should expect a short, sharp victory. The Kim regime would have to be expected to have some staying power, and would have to be expected to be able to get in some blows of its own. The most likely denouement for this scenario is a months-long campaign that would involve allied boots on the ground in the North. The most likely endgame would see China step in to stabilize the situation, with large swaths of North Korean territory marked out for post-conflict administration and humanitarian action while the international community figures out how to pick up the pieces.

For its part, while North Korean military and political leaders would almost certainly do their best to put up a fight, the much-feared North Korean army would almost certainly perform poorly, being trained and configured for offence and not well-prepared, as the recent successful defection of a North Korean soldier in the DMZ clearly illustrated, for situations that catch them by surprise and force them to react. It would be naive to assume that Seoul could get off scot-free, but the amount of damage North Korea could inflict on Seoul would be dramatically less than if it managed to attack first.

So far, there is no reason to fear that North Korea could manage to launch a long-range missile and have it successfully deliver a nuclear warhead on a distant American target. U.S. intelligence is uncertain about whether North Korea has mastered the ability to mount a nuclear warhead on shorter-range missiles, such as the Nodong or Taepodong 1 or 2, but for the sake of prudence assumes that it has. This potentially puts all of Japan within nuclear range. However, North Korea's older-generation missiles are notoriously unreliable, prone to exploding or breaking up in flight, and it would be something of a feat for North Korea to issue nuclear orders, transport warheads to missile batteries, fuel rockets, and fire them successfully, having been caught by surprise and under intense aerial attack.

Notice that there is nothing in this scenario about the use of U.S. nuclear weapons. If the United States chose to use nuclear weapons against North Korea, it could accomplish all its initial military objectives much more quickly and much more effectively, but only at an almost-certainly unacceptable political cost, both domestic and international. Moreover, attacking North Korean targets with nuclear weapons would contaminate large areas that would have to be occupied to restore order and humanitarian services. If the United States decides to jump through what it perceives to be a closing window of opportunity to denuclearize North Korea, it will almost certainly do so with conventional weapons alone.

In the second scenario, North Korea decides that a U.S. attack is inevitable – most likely, imminent – and gets in the first blow. Again, it would attempt to do so from the coldest standing start possible, but there would be no avoiding moving troops and equipment to the DMZ, and it is doubtful that they could succeed in springing a complete surprise as they did in 1950. North Korea might manage to avoid not tipping its hand to signals intelligence, relying as heavily as it does on landline communications, but it cannot escape virtual round-the-clock satellite surveillance.

There is relatively little mystery about the consequences of a North Korean attack. Estimates of the death toll in Seoul alone range from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands killed and widespread damage to the heart of South Korea's economy. Sleeper cells – those still active and not "cold," at any rate – would add to the chaos as they could through acts of sabotage, terrorism and assassination. North Korean forces would storm across the DMZ and drive as far south as they could in the face of whatever resistance South Korean and American troops could offer, which would itself depend largely upon amount of warning. But at some point, and before too long, they could run out of fuel and the offensive would grind to a halt, probably within five to seven days.

From that point on, North Korea would be on the defensive, holding out as long in hopes that this would be long enough to persuade the international community to come to the negotiating table with some arrangement that would at least secure North Korea's sovereignty and continued Kim family rule. Only once Mr. Kim saw the handwriting on the wall would he likely contemplate a nuclear option, as any North Korean nuclear use would almost certainly galvanize the international community's resolve to take him down.

The nuclear option, illustrated

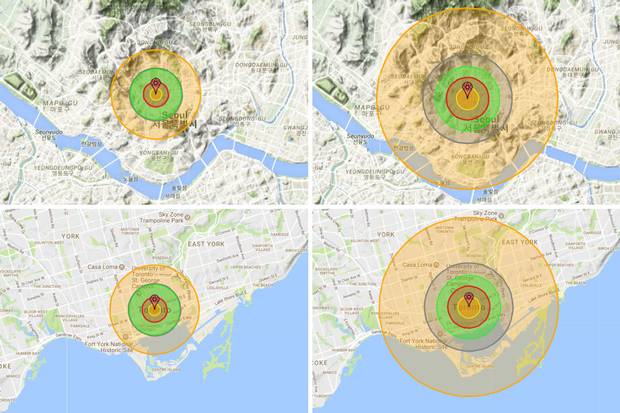

On Sept. 3, North Korea’s state news agency released this undated photo of Mr. Kim giving guidance on a nuclear-weapons program, as Pyongyang announced what it claimed was its biggest nuclear test to date. South Korean officials estimated at the time that the underground detonation was 50 kilotons, or the equivalent of 50,000 tons of TNT, but another analysis by the U.S. think tank 38 North said it was 250. Either way, the result would be devastating if, as a last resort, the North Koreans launched a nuclear attack on the South.

KCNA/REUTERS

Here’s how 50- and 250-kiloton strikes would look on the Nukemap, a simulator created by researcher Alex Wellerstein. Above, the impact of a strike on Seoul; below, comparable impacts in Toronto. The small orange circles are the fireballs; in the grey circles, the air blast would be powerful enough to collapse most residential buildings; and in the big orange circles, it would be hot enough to cause third-degree burns in humans.

NUCLEARSECRECY.COM/NUKEMAP

A U.S. nuclear strike on North Korea is virtually unthinkable because of the high loss of life and contamination to large areas that would have to be occupied to restore order and humanitarian services. But if the Americans did use nuclear weapons, they have more of them than any other country on the planet except Russia.

Is there a way to avoid war on the Korean peninsula? The best possible endgame would see someone high up in the North Korean leadership decide that their own long-term interest, and that of their family and compatriots, would be best served by taking matters into their own hands, eliminating Mr. Kim and his enablers, and signalling a willingness to co-operate with the international community. One would imagine that some in Pyongyang must already be thinking along these lines, but there is no way to know how many or whether they could organize a successful coup without being caught.

Failing a Made-in-Pyongyang solution, the only other way to avoid war is for either Mr. Trump or Mr. Kim to back down and accept what they have thus far said is unacceptable. For Mr. Trump, that would mean living with a nuclear-armed North Korea that can hold major U.S. cities hostage, coupled with the humiliation of being cowed into submission by Little Rocket Man. For Mr. Kim, it would mean giving up what he apparently seems to believe is the only thing preventing him from suffering the same fate as Mr. Hussein in 2003 or Moammar Gadhafi in 2014 – the very thing, moreover, upon which he has staked his legitimacy.

One thing is for sure: The status quo is untenable. One way or another the standoff must end, and probably sooner rather than later. Let us hope that when the resolution comes, it comes at the lowest possible human cost.

THE KOREAN STANDOFF: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL