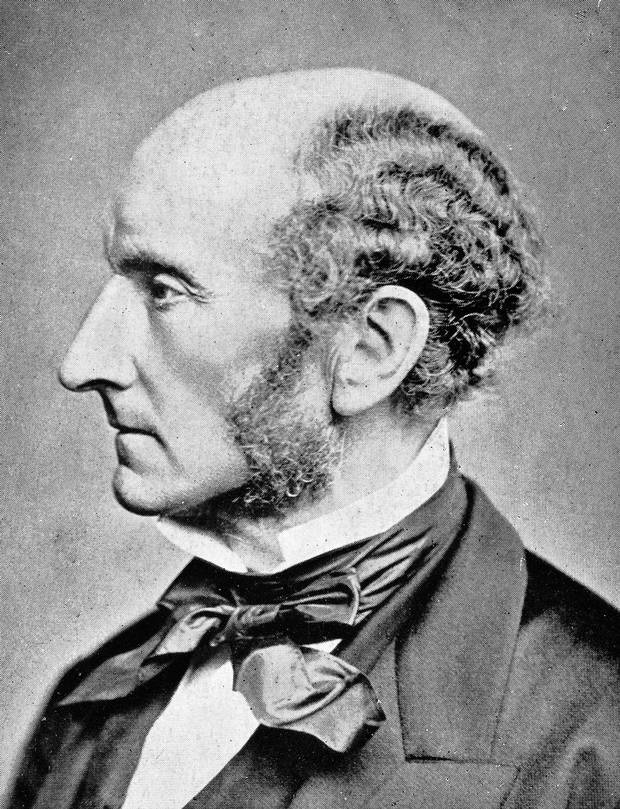

Perhaps you, too, would be grouchy if you've been dead since 1873. Or perhaps you would be perfectly serene. "Grouchy" better described John Stuart Mill upon his ghost's return from a recent visit to Canadian university campuses. He noted in this interview exclusive to The Globe and Mail that British North Americans ("or Canadians, as they now call themselves") still pay him lip service as the great founder and patron of free speech. He complained, however, that they no longer seem to understand what he intended by the term.

Mill's seminal On Liberty is rich in argument and abounds in brilliant formulations. He was a great journalist as well as a leading thinker. But if I had to choose one from all the rest, it would be this one: "But the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the present generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth, if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error."

There is something Socratic in this last notion: That just as Socrates forever tested his understanding by engaging his fellow Athenians in discussion, so we must always test ours by exposing our fellow citizens to alternatives.

Mill was not naively confident that truth would prevail in any collision with error. His argument was rather that it had to be heard in order to have any chance of doing so.

Nor did he think that freedom of speech was practical for every society – only those that had reached a certain stage of maturity. Canada qualifies, however, as would any successful liberal democracy.

To be sure, Mill endorsed suspending free speech when it posed a "clear and present danger" to the lives or property of any individual or group. But he opposed restricting it further. He did not wish to chill criticism, not even when it was harsh and directed at particular groups. I am Jewish, and criticism of Jews, Judaism or Israel often pains me. Still, I cannot, on Millian grounds, claim for any of the three any exemption from criticism. (Nor, of course, can the critics abridge my right of response.)

In its recent whirlwind tour of Canada, Mill's ghost touched down at several campuses. It fluttered away from them perplexed. Mill had expected to find our universities bulwarks of his principles but discovered that in fact these principles were hotly contested. A good example, much in the news, was Wilfrid Laurier University. There a dispute over teaching materials generated rival statements on free speech.

Four Laurier professors responded to the dispute by circulating a petition urging the university to adopt a policy modelled on that of the University of Chicago, since adopted by several other U.S. colleges and universities. This policy is strongly Millian. Indeed, Mill told me he would have broken his ghostly silence and signed the petition himself had not the authors requested signatures from the Laurier community only. He particularly endorsed the following paragraph: "It is not the proper role of our university to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. Although our institution greatly values civility … concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community."

"However offensive or disagreeable" – that cuts to the heart of the matter.

A rival statement on the issue emerged from some colleagues in the communications program, who, while conceding that "public debates about freedom of expression [were] valuable," insisted that they "can have a silencing effect on the free speech of other members of the public." Nothing in their statement supports this claim, however, which should be swallowed with a sizable grain of salt. "Charges that our program [in communications] shelters students from real-world issues or fosters classrooms inhospitable to discussing contentious issues from different vantage points seem to us simply preposterous."

Such charges may seem less preposterous to readers of the statement, the purpose of which was to defend two colleagues who had stopped at nothing to silence just such a different vantage point.

Yet another such statement was issued by the Rainbow Centre, an official entity of the university that advocates for queer and trans students. It protested that "the discourse of freedom of speech [was] being used to cover over the underlying reality of transphobia that is so deeply ingrained in our contemporary political context." Nothing is more predictable on campuses by now than the claim that a given liberal practice that presents itself as emancipatory is actually repressive.

In the present case, like any other, such a claim requires such substantiation as can only occur through free debate itself. Either the claimants can offer persuasive reasons for their position, and refute all objections to it, or they can't.

Or would any such discussion, according to them, just compound the problem by cowing even further those whom free speech is alleged to silence? If so, how to proceed? Must we cave to these petitioners, for want of their permission to challenge them? In casting the discourse of free speech as oppressive, statements such as the one just quoted imply that to curb it would be liberating. And so it would be – for those who got to do the curbing.

The basic premise of the opponents of free speech, namely that its very practice actually silences this or that group, casts the group in question as a basket case and encourages it to regard itself so. It treats the university as a sheltered workshop, some members of which require protection from the opinions of the rest. The most extreme version of this argument is that these students feel (and so must be deemed) unsafe when exposed to opinions uncongenial to them. A safe campus is a tame campus, from which students have a right to graduate unchanged, toting the same basket of congealed opinions with which they arrived.

This rejection of adverse opinions as "unsafe" would have driven Mill up the highest wall in Westminster. He argued the opposite: that we are safe only for so long as we are exposed to opinions contrary to our own – safe from our unfortunate proclivities to sloth, narrowness and prejudice, safe from forever riding in triumph over the corpses of straw men. He thought that there was no surer sign of a bad argument than its holder's insistence on its immunity to challenge. He also held that once any group claimed for itself the pious right to police unwholesome views, woe to any that differed from its own. Mill thought this the clear lesson of history – and he was right.

The dispute at Laurier must still be resolved – the administration awaits an internal panel's recommendations. It hasn't been the only one in Canada recently, and others are bound to occur. The current lot differ from those known to Mill in that now it is the self-anointed forces of progress that argue for narrowing the discussion to one whose terms they get to dictate. As U.S. sociologist Rogers Brubaker has put it: "These tendencies point in an increasingly and disturbingly illiberal direction. They threaten to transform the university from a space of free and unencumbered exchange into a space of constrained, monitored and inhibited exchange. They threaten to remake the university into a disciplinary institution in the Foucauldian sense, one that seeks – through an expanding array of training programs and through the proliferation and expansion of investigative and disciplinary bureaucracies – to produce docile subjects who will speak in institutionally correct ways."

Some ghosts remain relevant. Mill hoped to foster not docile subjects but democratic citizens who would take pride and even delight in the give and take of opposing arguments. He called on liberal democrats to develop thick skins, without which full debate over crucial issues (including the self-criticism on which genuine social progress depends) would be impossible. He was right to issue this call, and our universities evade it to their detriment.