Canadians are among the highest users of antidepressants in the world, yet a drop-off in patents for the drugs in Canada may be signaling a waning interest among the pharmaceutical industry.

Experts say the decline is due to the already saturated market of anti-depressant drugs in the country, including a growing number of generic brands, and the wide-range of diagnoses that makes it difficult to pinpoint the best medication. That, alongside shrinking profit margins, leaves drug makers less inspired to invest in new drug formulas to treat depression.

Some experts believe Canada could be missing out on the latest in anti-depressant medication as a result, at a time when politicians and policymakers are putting a greater emphasis on recognizing and treating mental health.

According to a 2013 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada reported the third-highest level of consumption of antidepressants between 2000 and 2011, behind Iceland and Australia. The OECD figures show Canadians consumed 86 daily doses of antidepressants for every 1,000 people per day in 2011, which was above the average of 56 doses among the 23 countries studied.

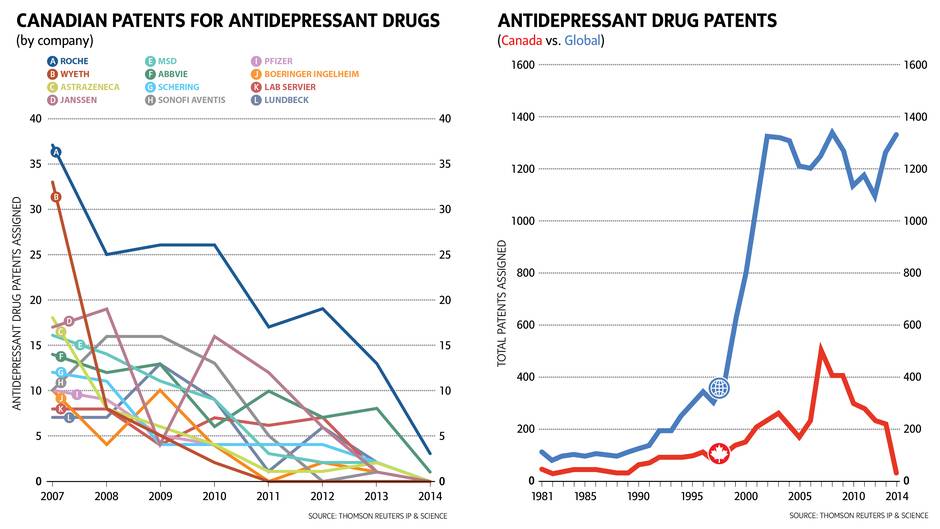

In the meantime, data from Thomson Reuters IP&Science shows Canada’s patenting for anti-depressant drugs has slid significantly from a peak in 2007 to almost no activity in 2014. The data looks at global inventions that are covered by Canadian patents or patent applications. Based on an analysis of the Derwent World Patents Index, experts say there is no significant delay in processing causing the trend.

“Patent registration is a proxy of the fertility of the market and the extent to which the private sector appraises the landscape and sees opportunity for growth,” said Dr. Roger McIntyre, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at the University Health Network.

“When we hear there are no seeds being sown, that’s quite an indictment of the landscape.”

McIntyre describes the patent-protection market in Canada as “anemic,” which allows for a number of generic drugs to hit the market. That leads to lower prices and a drop in margins for companies creating and selling anti-depressant drugs. As a result, drug companies –– most of which are large, multinational corporations –– are discouraged from registering patents in Canada.

"Strategies for pharmaceutical companies are international, not national."

"Strategies for pharmaceutical companies are international, not national."The industry shares some of the responsibility, McIntyre said, since it hasn’t created major advancements in the drugs to treat depression, other than in areas such as safety and tolerability.

“There has been some plateau in terms of innovation,” said McIntyre, while noting that it can take up to 15 years to bring a new drug to market.

Dr. Christopher Longo, associate professor of health policy and management at McMaster’s DeGroote School of Business, said the drop in patents comes down to a business decision for drug makers. Companies need to evaluate how crowded the market is to treat a particular disease, and if they have a drug that’s novel enough to address unmet needs.

“In a market where the needs for a particular disease are being met fairly well by existing medications, and where there are several medications available to treat that disease, a new pharmaceutical company entering the market really isn’t motivated to try to create new medications,” said Longo. “The opportunity for them to make significant profits doesn’t exist.”

That’s despite the Canadian government’s aggressive strategy to help manage mental health through the establishment of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, which has been calling for government spending on preventing and treating mental illness.

“You’d think that would make pharmaceutical companies want to jump on that bandwagon,” said Longo. “But the thing you have to remember is that strategies for pharmaceutical companies are international, not national.”

Canada represents roughly 3 per cent of the world’s market for pharmaceuticals, Longo notes.

Another challenge for patent activity is the wide range of diagnoses for depression, which can make finding and targeting drugs more difficult, said Dr. Sidney Kennedy, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and the Arthur Sommer Rotenberg Chair in Suicide Studies at St. Michael’s Hospital.

That, in turn, can make it difficult to develop a medication that’s right for one of the many subgroups of people suffering from depression

Kennedy also said the rise in generic drugs on the market can be a deterrent for companies looking at new formulations.

“I think the patent questions also relates to the somewhat naive view in the general public … that the generic equivalent, at a cheaper cost is the best way to go. So there’s less inventive for many of the large companies to be creative and take risks,” said Kennedy, noting that pharmaceutical companies are generally conservative.

Numbers are step one. Capitalize applies context to data – helping professionals leverage powerful information to make confident decisions. For more information, go to www.thomsonreuters.ca

Now experience Thomson Reuters Exchange. A new digital publication for fresh ideas and insights in a dynamic, interactive format. Download the free App from the App Store, Google Play and Amazon Appstore.

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's advertising department, in consultation with Thomson Reuters. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.