If you’ve been to a Walt Disney World theme park in Florida lately, chances are you got in after opting to place your index finger on biometric scanner and scanning a wristband that you pre-received in the mail.

Behind the scenes, Disney’s program has become one of the largest commercial applications of biometrics and wearables in the world. For years now, companies like Disney have been collecting your biometric data – human body characteristics – and using it to subtly encourage you to engage more and spend more.

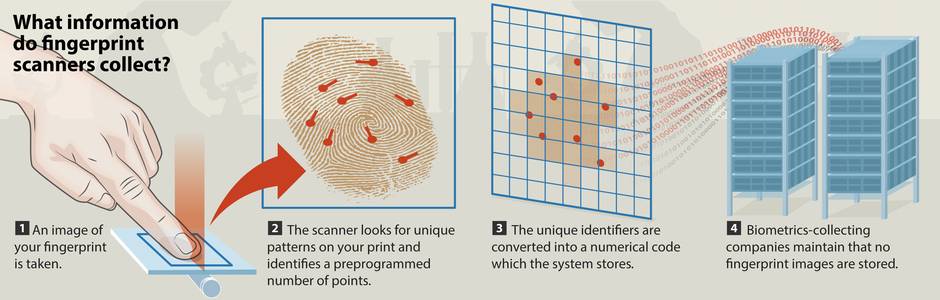

Disney insists their MagicBands don’t store personal information, and what’s collected is aggregate data to help it better serve guests. Fingerprints are also not collected, but instead fingerprint information that can ease entry and prevent fraud.

Still, there are skeptics amid increasing concerns about the collection and safeguarding of personal information. Those worries are expected to grow given the popularity of products such as the new Apple Watch and fitness-tracking products like Fitbit and Nike’s Fuelband. Consumers are becoming more addicted to the technology and are willingly providing personal information in exchange for more effortless and interactive experiences.

“It’s convenience versus privacy,” says Jason Thomas, manager of innovation for the government segment of Thomson Reuters. “The question it comes down to is: Are you willing to enable giving up that privacy in order for things to be more convenient? It’s a personal risk decision.”

There are so many companies now collecting personal data, most consumers have lost track of what they’ve allowed, Thomas says.

For example, each of Disney’s Magicbands are equipped with a short-range radio frequency identification chip, which in exchange for being able to track you across the park and link to your credit card, allows you to do everything from reserve rides to place food orders without standing in long lines. For an especially magical experience, visitors with reservations to the Be Our Guest restaurant find that employees know exactly where you sit and what you want without ever asking the question.

More than 10 million guests have used the MagicBands since their official launch in 2013, the company says. The program, which cost about $1 billion (U.S.) to implement, had “a positive impact to the bottom line,” in its first quarter of fiscal 2015 and that it’s"just the beginnings of it,” Disney CEO Robert A. Iger told shareholders in a conference call.

“We are witnessing a new generation of privacy challenges arising from the combination of seemingly innocuous and non-sensitive bits of personal information to derive insights into personal behaviour,” states a recent report on wearable computing from the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC).

The report says people already find it challenging to decide what information to disclose. What’s more, most don’t fully understand how their information may be used, or combined with other data, in the future.

“Wearable computing devices that are constantly collecting, processing and sending data are likely to compound this problem,” the report states.

Some people are pushing back. An example is a student writing the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), who complained to the OPC about the collection of fingerprints and other personal information to confirm the identity of people writing the test, including how it was being kept and secured.

The OPC investigated the collection of biometric information for the MCAT, as well as the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) and the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT). It ruled that organizations offering these “high-stakes examinations” need to collect the minimal amount of personal information, and that it needed to be kept safe for a “reasonable length of time.”

There are no biometric-specific laws in Canada. Instead, the collection of information falls under legislation such as the Personal Information Protection and Electronics Document Act (PIPEDA), which applies to all organizations that collect, use and disclose personal information as part of their business activities. Quebec has a law that deals with how biometrics information is collected, which says it must be disclosed to the information commission.

“We are probably in early days at this point to have a full appreciation of what should even be of concern,” around the use of biometrics data, says Alex Cameron, a partner and privacy and cyber security expert at Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP.

Consumers may be using the technology, but Cameron says there are still anxieties about how the information is being collected and used, as well as the potential for data breaches.

The long-term risk is that biometric information could become “part of an identity thief’s tool kit,” Cameron says.

There are also concerns about cross-border transfer of data, for example, and what the U.S. can do with information collected from Canadian citizens.

Cameron says Canadian law often governs these transactions. At the same time, cross-border processing of information about Canadians, for example, in the U.S, is generally considered permissible under Canadian privacy law. Still, there are obligations to provide a comparable level of protection (using contracts and safeguards) and to give individuals notice that their information is being processed outside of Canada and may be subject to disclosure under foreign laws.

For many consumers, biometrics and wearables are valuable combination of technology that helps to improve quality of life – or at least an attempt at it. For example, fitness bands are becoming a common site on the wrists of Canadians wanting to track and measure their health and physical activity.

“There’s an obvious consumer opt-in to that,” says Cameron. “The question is, what else is going to be done with that information? What are you consenting to?”

Cameron says it’s important for consumers to read and understand what consent they’re giving when using these types of technology.

The growth and acceptance of biometrics and wearables will likely come down to consumers’ comfort that the information they’re providing won’t be used in a way they see as negative in the future.

“It matters what the objective is, what the level of sensitivity of the information is, and what’s the ultimate benefit – and balancing those things out,” Cameron says.

For more information on wearables and other emerging technology, visit Jason Thomas' website.

Numbers are step one. Capitalize applies context to data – helping professionals leverage powerful information to make confident decisions. For more information, go to www.thomsonreuters.ca

Now experience Thomson Reuters Exchange. A new digital publication for fresh ideas and insights in a dynamic, interactive format. Download the free App from the App Store, Google Play and Amazon Appstore.

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's advertising department, in consultation with Thomson Reuters. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.