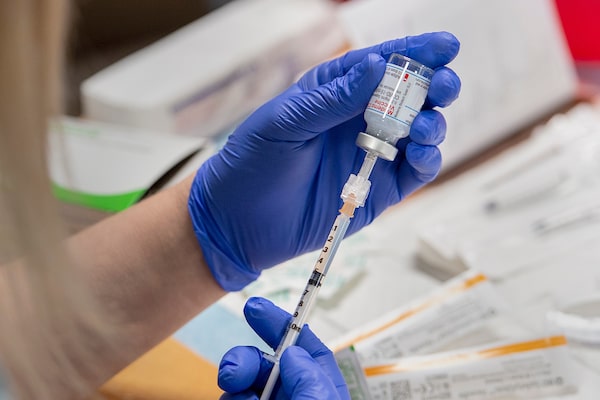

Amanda Parsons, a registered nurse on staff at the Northwood Care facility, prepares a dose of the Moderna vaccine in Halifax on Jan. 11, 2021.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press

Is the federal government’s COVID-19 vaccination program turning into the Ross rifle of our time?

In the First World War, Canadian troops arrived in Europe with the Ross Rifle Mark 3, which was very accurate, but had a tendency to jam and could not cope with the mud of the trenches.

The rifles were so unreliable that Canadian soldiers took Lee-Enfield rifles from the bodies of dead British soldiers, so at least they would have something to shoot with. The Ross rifle stands as an early example of the federal government’s chronic failure at procurement, with fatal results.

A little more than a century later, Canada ranks behind almost every other developed country in procuring vaccines to immunize its population against COVID-19. This could also prove deadly, especially for the frail elderly who need protection yesterday.

Getting the jab done: When can Canadians expect to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

The other countries of the Anglosphere are all doing better. Australia and New Zealand beat back the disease (it helps to be an island), while the United States and Britain, which otherwise mishandled the pandemic badly, have delivered impressively on vaccinations. While Canada struggles to fully immunize the frail elderly, in the United States some people in their 60s are now eligible for shots.

Germany, France, Spain and Italy, after a slow start, have caught up to and surpassed Canada. The Poles are ahead of us. The Portuguese. The Greeks.

Meanwhile, humanitarian groups condemn Canada for drawing down from a vaccine supply supposedly intended for developing countries.

Part of the problem with Canada’s response is the fear of risk built into government decision-making.

“Governments have a hard time with procurement,” said Robert Schertzer, a professor of political science at University of Toronto who studies Canadian federalism. “Part of that is risk aversion.” Bureaucracies are reluctant to make commitments that could turn out to be wrong or wasteful, he observes. “This can make it difficult to buy stuff.”

In the pandemic, hesitancy might have been made worse by Canada’s inability – or failure – to counter rising vaccine nationalism by ramping up domestic capability.

Another reason that Ottawa is not good at buying stuff and delivering services is that it doesn’t do it much. Provincial governments are responsible for delivering education, health care, plowed highways. The feds collect revenue and disburse it. They do this well, as we saw with the CERB and CEWS programs for workers and businesses affected by the pandemic.

Where Ottawa is directly responsible for buying and delivering stuff, such as to First Nations or the military, governing parties are able to escape political responsibility for mistakes because relatively few voters are involved. No governing political party has been defeated at the polls over boil-water advisories or the inability to choose a jet fighter.

But the whole country is counting on the federal government to procure vaccines. Voters won’t tolerate failure. The Ross rifle fiasco cost defence minister Sam Hughes his job. What price might Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pay for vaccine stumbles? That depends on what happens over the next few months.

The Liberals insist that six million Pfizer and Moderna doses will have arrived by the end of March, offering protection to the most vulnerable, with the rest of the population receiving doses in the following six months. If Canada has caught up with most other developed nations in vaccinating its population by April or May, then the Liberals are unlikely to take much of a political hit.

But if vaccination rates chronically lag behind other countries in the Anglosphere and Europe, then voters will be furious. God help any political party, at any level of government, that gets blamed.

Other aspects of the Liberals’ pandemic response, in supporting workers and businesses, procuring personal and protective equipment, and protecting borders, have ranged from admirable to mediocre.

But that shouldn’t surprise anyone. As Prof. Schertzer points out, “Canadian exceptionalism rears its head in how we assess our governments sometimes.” We want our country to excel. But Canada is a mid-sized developed state. We shouldn’t expect our handling of this crisis to be other than middle-of-the-pack.

The effort to acquire vaccines does not have to become the Ross rifle of our time. But the Liberals needs to start delivering results, and soon.

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.

John Ibbitson

John Ibbitson