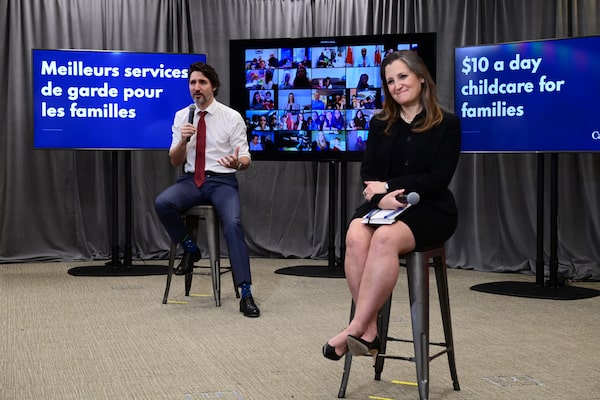

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland speak to parents during a virtual discussion on child care in Ottawa on April 21, 2021.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

If you’re a provincial premier, you should be wary of Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s proposal for a shared-cost child care program. Because if past is precedent, your successors will end up footing the bill.

The Trudeau government wants to swiftly implement a program that will allow parents across the country access to child care for $10 a day. The first step is to negotiate federal-provincial agreements that will halve the cost of existing regulated child care by the end of next year. Once it is fully implemented, Ottawa and the provinces will each be contributing $8.3-billion to operate the system.

Ottawa promised $10-a-day child care in the 2021 federal budget. How would that work? A guide

That was how Canada funded public health care back in the day. The Medical Care Act of 1966 proposed a 50-50 shared-cost program to cover services provided by doctors. It took six years for all provinces and territories to sign on to the new system. But by the mid-1970s, federal finances were already feeling the strain.

In 1977, all sides agreed to a new system that involved block grants accompanied by a transfer of tax points, in which Ottawa reduced its taxes and provinces increased theirs by the same amount. But as federal deficits piled up year after year, the Mulroney and Chrétien governments began scaling back the block grants. By 2000, federal cash transfers accounted for only 15 per cent of provincial health care spending. Although the Martin, Harper and Trudeau governments all put money back into the system, federal transfers still fall below the original promise of sharing the burden equally.

There are similar stories to be told in public housing and welfare. Ottawa barges into an area of provincial jurisdiction with an offer to pay half the cost of some new program. But then federal priorities shift, and provincial governments are left paying an ever-greater share of the cost of maintaining said program.

Even if this Liberal government is able to persuade provincial counterparts that Ottawa can be counted on to maintain its share of the funding over decades, negotiations will be fraught. Quebec already has a subsidized child care program. But the province is every bit as entitled as the others to this new federal transfer, which it will want to spend as it sees fit.

Most other provinces already have some version of support for lower-income parents, such as the Saskatchewan Child Care Subsidy or the Ontario Child Benefit. Will they be folded into the provincial contribution for the new program?

Then there is the question of equalization. Sir John A. Macdonald bribed Prince Edward Island into entering Confederation by having Ottawa take over its debt. From then until now, the feds have come to the aid of poorer provinces unable to shoulder their responsibilities.

Ensuring provinces can offer similar levels of social services at similar levels of taxation is constitutionally mandated. So if a national child care program goes ahead, and Newfoundland and Labrador - which is on the brink of insolvency - says it cannot afford a single dime to improve child care, then Ottawa will be constitutionally obliged to provide the necessary funding.

For Shirley Tillotson, professor emeritus at Dalhousie University and a specialist in the history of fiscal federalism, “these issues are part of a problem that already needs to be addressed: the disproportion that has emerged between provincial responsibilities and their fiscal capacity.

“The child-care program just intensifies the problem to the point where it must be addressed by some real changes in fiscal federalism,” she told me in an e-mail exchange.

But in the meantime, the Trudeau government will employ an asymmetrical (a fancy word for piecemeal) approach of tailoring the program to fit each province’s capacity and willingness.

Conservative premiers in Ontario and the Prairie provinces may not be willing to engage at all. In that case, the national child care program may consist, at least in the early stages, of free money for Quebec, majority federal funding in the Atlantic provinces, a more balanced agreement with British Columbia’s NDP government, and no agreements in place with the provinces in between, though everyone knows that a) all provinces will eventually sign on, and b) Ottawa will eventually start to cut back its contribution.

Let the negotiations begin.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

John Ibbitson

John Ibbitson