At a lunchtime campaign stop in the town of Fergus, Ont., in April, the lineup to see Pierre Poilievre wound around the hallways of a recreation centre.

Two nights earlier, his downtown Toronto rally finished with hundreds standing in a serpentine line for 90 minutes, waiting to take a picture with him. Many hadn’t been to a political event before.

It’s a scene replicated in towns and cities across the country, with a cross-section of traditional conservatives, trucker-convoy fans and 30-somethings worried about home prices coming out in droves to see Mr. Poilievre.

What Mr. Poilievre offered to those crowds is his uncomplicated explanation of what has gone wrong.

It’s something he absorbed as a teenager and has preached ever since: Big government overreaches, taking away our personal choice, our economic freedom and our money. Now people are embracing the message – and the messenger.

They watched him command stages with a radio-announcer’s voice, a broad smile and a sense of his audience’s frustrations. He talked about teenagers depressed by lockdowns and an unvaccinated mom getting fired.

He told the crowd in Toronto about a couple in a trailer park near his home in Greely, who work in a quarry making materials for building houses, but calculate they’ll never afford one of their own.

“When the people who build our houses cannot afford to live in them, we have a fundamentally unjust economy, my friends,” he told his listeners.

The problem, he said is “big, bossy government” telling people what to do, and spending so much it caused inflation that clobbered ordinary folks.

He’s a proselytizer. Mr. Poilievre preaches small-government conservatism while digging both hands into the mucky trenches of partisan politics, ruthlessly pushing aside questioners as Liberal unbelievers. He has spent decades whittling free-market economist Milton Friedman into accessible phrases for main street.

Mr. Poilievre watches Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the House of Commons on Sept. 15.Blair Gable/Reuters

There can be no doubt now that Mr. Poilievre has struck a chord with the Conservative Party base and beyond. He has become a social-media and viral-video personality. Hundreds of thousands signed up to back his leadership campaign, handing him a landslide first ballot victory.

At 43, the Alberta-raised MP is now Opposition Leader and, by Canadian political tradition, prime-minister-in-waiting. He takes the helm of the Conservatives as the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, now seven years in power, faces angry veins of pandemic frustration and economic angst fuelled by wallet-stretching inflation.

Mr. Poilievre declined an interview request for this piece, and largely avoided sitting down with the media after he solidified front-runner status.

The Globe interviewed dozens of current and former colleagues, staff, associates and friends, although many were reticent to be named as it became clearer Mr. Poilievre would be the new Conservative leader.

He won the leadership by seizing the momentum of the so-called Freedom Convoy – with its motley mix of pandemic-measure protesters, vaccine opponents and conspiracy theorists – that rolled into Ottawa in January, garnering crowds and donations.

Mr. Poilievre railed against vaccine mandates, insisted the whole movement was not responsible for racist symbols or anti-government manifestos raised by some, and never called for the blockades to stop.

A Poilievre sign hangs from a truck at the convoy protests in Ottawa on Feb. 16.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

His critics have labelled him a Canadian Donald Trump, and he has mirrored populist MAGA techniques. He built a social-media following bashing Liberal “elites,” played peek-a-boo with conspiracy theorists, and avoided contradicting those who insisted the World Economic Forum is secretly running Canada. At rallies, his culture-war calls to defund the CBC won the loudest cheers.

But he is no Donald Trump in tenets or temperament. He doesn’t echo the anti-immigrant rhetoric, and abhors Mr. Trump’s gargantuan deficits. He is so calculated that he could never be the erratic bundle of impulses that rambles at a Trump rally.

Away from cameras, there is another Pierre Poilievre: A quieter, private, wonky bookworm with a nerdy laugh who seems too affable to share a body with the political performer seen on YouTube demanding finance ministers give him yes-or-no answers.

In his lifelong political education, he has learned to turn opposition into opportunity, to delight at progressives clutching pearls while he grabs attention, and to never back away from fights.

His job now is converting those who feel they’ve been struggling to the message that big government is their burden.

That’s the mission he’s been practising for his whole life.

Mr. Poilievre and his wife, Anaida, stand up as he is declared the new Conservative leader in Ottawa on Sept. 10.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Mr. Poilievre has repeated his origin story many times in recent weeks. He was born to a 16-year-old unwed mother whose mother had just died, and adopted by two schoolteachers who had come to Calgary from Saskatoon. In fact, when his birth mother had a second son, Donald and Marlene adopted Patrick too.

His family’s heritage, Mr. Poilievre has said, is like Canada’s: “all mixed up.”

The Calgary kid was named Pierre because of Don’s franco-Saskatchewan heritage. Don’s grandfather, Joseph, had emigrated from France in 1904 to what would become Prud’homme, northeast of Saskatoon. Don’s father Paul farmed, ran a garage in Leoville, a hotel in Moose Jaw and settled into real estate in Saskatoon.

Marlene’s mother, Louise Schartner, had her daughter in rural Saskatchewan during the Depression, but separated from Marlene’s father only months later. His biological grandfather was an Irish immigrant from County Meath.

Don and Marlene married in 1971 and were older parents, on either side of 40, by the time they adopted Pierre in 1979.

Pierre’s parents were teachers through the rough recession of 1980s Alberta, and he described their standard of living, in the suburban southwest edge of Calgary on Shawnessy Drive, as modest. The boys could play hockey and go on camping trips. Pierre played sports and was on the wrestling team, until a teenage shoulder tendinitis forced him to stop.

That injury opened a door. He was a bored teenager, he told The Globe and Mail in a 2015 interview. And as he watched his mother head to an Alberta Tory riding-association meeting, 14-year-old Pierre begged to tag along. He caught the bug. He threw himself into politics, and started reading books.

A bust of economist Milton Friedman at the Stanford University campus in California.Paul Sakuma/The Associated Press

While still a teen, he found the book he has for 20 years described as his seminal influence: Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom. The book is Mr. Friedman’s argument that economic freedom is key to personal freedom, and that apart from limited cases where government action is needed for a greater neighbourhood good, government initiatives infringe on personal freedom.

Yet Mr. Poilievre’s biggest influence was surely participating in real-life politics, taking on adult roles as a teen. He went to meetings of both the Alberta Progressive Conservatives and federal Reform Party, knocked on doors in campaigns and served on a riding executive. A week after his 17th birthday, he was a delegate to Reform’s 1996 national convention in Vancouver. He did phone canvassing for a young Calgary Reformer running for the first time, future federal cabinet minister and Alberta Premier Jason Kenney.

But something apart from a shoulder injury was happening as he threw himself into politics: His parents separated. In his mid-teens, Pierre was shuffling between Shawnessy Drive and his father’s new home. Eventually, Don came out as a gay man.

In his Sept. 10 victory speech, Mr. Poilievre for the first time spoke of his father and his long-time partner’s relationship publicly as he acknowledged both of them in the audience.

In the mid-1990s, there were still few openly gay politicians and celebrities, and coming out came with more social vulnerability.

Shuvaloy Majumdar, a former Conservative staffer who met Mr. Poilievre when both were 18, said that among people Mr. Poilievre knew, his father’s sexuality was no secret.

“I’ve never seen him uncomfortable with his family. It was never something he hid or pretended didn’t exist or lied about,” Mr. Majumdar said. “It was always, ‘This is who I am. This is where I come from.’”

At the time, debates about issues such as pension benefits for same-sex partners, including in the Reform Party, with its wide vein of social conservatism, included homophobic warnings that such measures would promote homosexuality.

“[Pierre] never thought the rights of sexual minorities was icky. He was never repulsed by those things. I think he was trying to understand the decisions his father was making for himself,” Mr. Majumdar said.

Perhaps, he said, the dislocation of his parents separating encouraged him to find his identity in a political community.

In 2005, as a rookie MP, he gave a speech opposing gay marriage, arguing civil unions would ensure equal rights while preserving the traditional definition of marriage. In typical Poilievre style, he blamed the Liberals. Atypically, he declared deep respect for those who disagreed with his stand.

Fifteen years later, in 2020, he told La Presse that he’d learned a lot and realized gay marriage is “a success.” When erstwhile Conservative leadership candidate Richard Decarie called homosexuality a choice, Mr. Poilievre tweeted: “Being gay is NOT a choice. Being ignorant is.”

Mr. Poilievre shakes hands at a barbecue during the Calgary Stampede this past July. He studied at the University of Calgary in the 1990s, where he got involved in conservative politics.Todd Korol/Reuters

If he was looking for his identity in conservative politics, Pierre Poilievre found himself in a hothouse at the University of Calgary in the 1990s.

A ‘Calgary school’ of political science professors was writing up a revival of free-market, individual-liberty politics, and student activists squabbled about the divide between the western-based Reform Party and centrist federal Progressive Conservatives.

At 19, Mr. Poilievre was already discovering opposition was an opportunity to get headlines. When the student union attempted to prevent campus Reformers from campaigning for their candidate in Alberta’s non-binding Senate election, Mr. Poilievre marched a protest across campus, through annoyed students in the food court, to the Goddess of Democracy statue, where reporters were waiting.

“Pierre, I think, discovered his natural talent,” Mr. Majumdar said.

Mr. Poilievre was among the Reformers on Alberta campuses pushing rock-ribbed, ideological conservatism, a group battling the federal PCs they derided as so politically flexible they lacked principles. Jeremy Harrison, now Saskatchewan’s Minister of Trade, but then a University of Alberta Reform activist, said they had a firm view about how to do it: “Never backing away from fights.”

The 2022 shots Mr. Poilievre’s leadership campaign took at former Quebec Premier Jean Charest for being a Liberal should come as no surprise. That’s pretty much how Alberta student Reformers like him saw Mr. Charest when he was Progressive Conservative leader in the 1990s. Some of their fights were directly with then-PC youth leader Patrick Brown, the erstwhile leadership candidate Mr. Poilievre repeatedly called a “liar.”

The “pre-Brylcreem Pierre,” a skinny kid in T-shirt, flannel, and jeans studying poli-sci, could be found with his nose in Milton Friedman’s Monetary History of the United States. But the debate-club, model-UN student wasn’t shy about making speeches: Mr. Harrison still marvels at how he’d walk in front of a TV camera or into a gym to make a speech.

“The guy you see giving speeches right now is same guy that you would have seen giving speeches when he was 19 years old,” Mr. Harrison said. “It’s remarkable. Even the content. Phrasing. Pierre’s views have not really wavered.”

At 19, Mr. Poilievre penned an entry for an “As Prime Minister” essay contest whose content would fit his speeches today. He was rewarded as a finalist with a four-month internship at Magna, the contest’s organizer, in what remains as his longest stretch of employment outside politics.

Reform Party leader Preston Manning and his wife, Sandra, greet supporters in Calgary in 1997, the year he set up an internship program that Mr. Poilievre would get involved in.Patrick Price/REUTERS

It was another internship that marked his political education, in a Reform Party program that blooded a remarkable generation of influential conservatives.

Reform leader Preston Manning asked senior aide Rick Anderson to launch an internship program for up-and-comers. The first iteration, in 1997, sent interns into Ontario on a school bus to knock on doors before the June election, “staying six to a room with cases of beer and pizza,” Mr. Anderson said.

Kory Teneycke, later prime minister Stephen Harper’s communications director and Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s election-campaign manager, ran the program. In the second year, he reorganized it based on the fellowship he’d done in Washington with the libertarian Charles Koch Foundation. Interns worked in MPs’ Parliament Hill offices doing research or correspondence, but also attended mandatory lectures. There was bonding. Mr. Poilievre was the guy who asked the wonk question in lectures.

“I guess if you’d asked any of his cohort of interns who would have been most likely to run for prime minister one day, he would have got the most votes,” Mr. Teneycke said.

Conservative operative Kory Teneycke, shown in 2015.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Of the perhaps 50 or 60 who participated in the program in its early years from 1997 to 2001, a remarkable number rose to become elected politicians and senior political staffers.

Mr. Poilievre, Mr. Harrison, and former leader Andrew Scheer all became MPs in their mid-twenties, in 2004. Mark Strahl and Shannon Stubbs were elected later. Ray Novak became Mr. Harper’s executive assistant, then chief of staff. Mr. Majumdar was senior policy adviser to former foreign affairs minister John Baird.

But one intern connection marked Mr. Poilievre’s life indelibly. Jenni Byrne, one of the first batch of Reform interns and later youth co-ordinator, became Mr. Poilievre’s friend, and the two struck up a decade-long romantic relationship that lasted until 2011.

She became Mr. Harper’s feared, take-no-prisoners fixer, deputy chief of staff and campaign manager, with a reputation, then and now, for ruthless tactics. Mr. Poilievre and Ms. Byrne are still friends, and she is effectively his chief strategist, guiding his leadership campaign and now working to make him prime minister.

Jenni Byrne at a 2009 federal cabinet meeting.Jason Ransom/Prime Minister's Office

Many of those early interns later crossed paths in junior staff jobs on Parliament Hill, and events of the Reform Party and its successor, the Canadian Alliance. Mr. Poilievre led a Calgary phone bank, dubbed Fight Club, for Stockwell Day’s Canadian Alliance leadership campaign.

In Calgary, he wrote a few op-eds with Mr. Day’s communications aide, Ezra Levant, now owner of right-wing site Rebel News. For a time, he had a side business with Jonathan Denis, later Alberta’s justice minister, doing robocalls for candidates.

In 2002, he left Calgary, leaving his degree unfinished for six years, to work for Mr. Day on Parliament Hill. One day, a group of junior staffers went to a meeting and were surprised by the topic: getting young Pierre Poilievre elected to Parliament.

In 2004, the Calgary kid had displayed enough ego to think he could get elected in the Ottawa-outskirts riding held by Liberal defence minister David Pratt.

To win the Conservative nomination, he knocked on doors at party members’ houses, looking like such a kid that local businessman Bill Ayyad, later his riding-association president, thought he was there to collect empty bottles.

According to two Conservative associates, Mr. Poilievre briefly thought about changing his name to Peter over concerns about his French name in semi-rural areas, but on Friday his office said this was not the case.

Mr. Poilievre displayed a pavement-pounding work ethic – a career-long hallmark – and, representing the newly united Conservatives, he won.

The 25-year-old told The Globe he wasn’t nervous about Parliament. “I know how the place works,” he said.

Mr. Poilievre speaks in 2006 to apologize for an obscene gesture the day earlier.Tom Hanson/The Canadian Press

Scott Simms, then a new Liberal MP from Newfoundland, attended an orientation with Mr. Poilievre and realized that he was a cut above the other new MPs because he had studied the craft of political performance. “Pierre was like every successful politician of the ‘80s and ‘90s wrapped into one kid,” Mr. Simms said.

That often got missed because by anyone’s measure Mr. Poilievre was a sharp-tongued, overconfident rookie. “I think a lot of people who show disgust at Pierre Poilievre, there’s a streak of jealousy in it,” Mr. Simms said.

He had a nose for a winning issue, pressing the federal government to sell a local hospital its land for one dollar. And when the Conservatives took power, he was made parliamentary secretary to Treasury Board president John Baird, and apprentice to a politician seen as a partisan pitbull.

Prime minister Harper’s young, swaggering PMO aides were derisively dubbed the “boys in short pants,” and Mr. Poilievre was seen as the parliamentary model. Some Tories mocked him as “Peter Polliver.” The acerbic Mr. Baird called him “Skippy.”

He had a knack for peeving opponents. After he was accused of making an unparliamentary gesture in 2006, Liberal veteran Ralph Goodale huffed that “this little boy needs some potty training.”

It was, in the eyes of his friend, Alberta MP Michael Cooper, who stayed in Mr. Poilievre’s basement when he was a Conservative intern in 2006, an effort to brush him off: “But he was not someone to be dismissed.”

Off the political stage, Mr. Simms got to know the low-key, friendly Mr. Poilievre while doing presentations for a school exchange from their ridings, and making jokes. In Commons committees, he observed the performer, wincing when he beat up on non-partisan civil servants, but marvelling at his talent for tailoring a message to his target audience – and being willing to attack those who weren’t part of it.

In the minority Parliament, he was a “spear-catcher,” in Mr. Teneycke’s words. He gummed up opposition efforts to pursue the so-called in-and-out election-financing scandal in 2008 with dozens of points of order, and suggested Elections Canada officials were out to get the Tories. And in the Harper era, when backbench MPs were expected to say little and stick to the script, he wasn’t afraid of making waves in front of a microphone.

By his 29th birthday in 2008, he was a second-term MP making six figures. A lot of people wanted to see the cocky young politician screw up. And he did.

Indigenous delegates watch prime minister Stephen Harper in the House of Commons in 2008, where he apologized for the abuses of Canada's residential schools. Mr. Poilievre's remarks on the apology would get him in hot water within the party.Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

As he rose in the Commons on June 12, 2008, Pierre Poilievre looked shell-shocked, gulping as he delivered “a full apology.”

The day before had been a landmark moment in Stephen Harper’s tenure. He had delivered a historic apology for residential schools. Indigenous leaders filled the Commons galleries.

Then Mr. Poilievre stepped on the moment in a radio interview.

Mr. Harper’s apology, he told Ottawa radio host Steve Madely, came with $4-billion in compensation. “Some of us are starting to ask, ‘Are we really getting value for all of this money, and is more money really going to solve the problem?’ My view is that we need to engender the values of hard work and independence and self-reliance.”

The next day, Mr. Harper dressed him down so sharply that people outside the room were embarrassed. Then Mr. Poilievre, a back-bench MP, was hauled into the cabinet’s prep session for Question Period to go over his part in the damage control, a pre-QP apology. His face was flushed, as if he’d brushed away tears. Ministers avoided Mr. Harper’s gaze.

Mr. Poilievre might have felt his political career was hanging by a thread.

For months afterward, with the 2008 election in between, he seemed more withdrawn, less aggressive, former colleagues said. Several said he learned a hard lesson to choose words deliberately. They differ on whether it taught him to be wiser or more clever. But he knew he had overreached.

Mr. Harper and Mr. Teneycke in Washington in 2009.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Yet Mr. Poilievre had advocates in the PMO, Ms. Byrne not least, and according to Mr. Teneycke, Mr. Harper liked his fight.

The PM named him his parliamentary secretary – an appointment that was both promotion and penance. It meant he sometimes fielded more questions than cabinet ministers, constantly deflecting and defending awkward questions. “In that regard, it is a thankless job,” Mr. Cooper said. Mr. Poilievre privately admitted to some he hated it.

When he was named to cabinet as a junior minister just after his 34th birthday, it was his tactical political skills that were being mined.

His primary job as a junior minister responsible for democratic reform was pushing a controversial Fair Elections Act that among other things would restrict Elections Canada’s role in promoting voting to young people and Indigenous peoples. When the non-partisan chief electoral officer, Marc Mayrand complained, Mr. Poilievre retorted that he wanted more money and power.

What was unusual about Mr. Poilievre’s ministerial style was that he did so much himself. Even when he gained a full staff as a senior minister in 2015, he delegated tasks more than responsibility. He especially controlled the message. He wanted punchy, tabloid-style simplicity. He didn’t need a draft speech; he knew what he would say. He had a press secretary, but sometimes drafted press releases.

He hasn’t fully abandoned those ways now. Trademark leadership-campaign phrases, like “fire the gatekeepers,” came from him. His sophisticated social-media leadership campaign was managed by a team, but the building of his online brand was, according to a friend, “all Pierre.”

In 2015, he was shuffled into a massive department, Employment and Social Development, but with eight months to an election, his key task was promoting the Universal Child Care Benefit cheques the government sent to parents. He crisscrossed the country, ostensibly searching for eligible parents who hadn’t applied, then promoting an expansion of the benefits – with a mock cheque made out to parents on his podium.

Mr. Poilievre wears a blue Conservative Party shirt in Halifax in 2015.Andrew Pinsent, News 95.7 (CJNI Halifax)/The Canadian Press

In Halifax, he had another idea. Unbeknownst even to his political staff, Mr. Poilievre showed up for the government announcement in a blue golf shirt with a Conservative Party logo. And it created an immediate uproar: The minister had turned government business into partisan campaigning.

But Mr. Poilievre had a simple explanation for blindsided aides: Without the logo controversy, the announcement wouldn’t have made it onto TV news. Ordinary families wouldn’t care about a logo – but they’d remember the cheques.

The shirt was no accident. And it was no exception, then or now. The provocative statements, marching with convoy figures, saying he’d fire the Governor of the Bank of Canada – none of it is shooting off at the mouth. He is calculated. Sometimes that means reaching his target audience by upsetting another group – preferably progressives or Liberals.

There is some savouring of that as payback from a politician who, despite decades in the corridors of power, claims to speak for those treated with disdain by the establishment, Liberal politicians and the media.

He strives to speak in simple language. In a 2015 interview, he derided the “modern-day Latin” politicians use. His constituents, he said then, have pragmatic concerns, and barely hear the criticism that he’s overly partisan.

Even colleagues and staff who weren’t fans of his were amazed by his energy, long hours, and capacity as a message machine. He could deliver the same speech flawlessly in different towns, adjusting for local details or anecdotes, without even a piece of paper. In fact, some found it disquieting that he was so unrelentingly self-scripted – everything, every word, planned and practised to robotic efficiency.

As party leader now, he won’t be able to control so much directly, however, and he has yet to lead an organization where he has to hand off major responsibilities or manage big egos.

He is something of a solitary figure. He has a few friends, like Mr. Cooper, but he is not the centre of a social circle. Although he’s known some Conservative MPs for 20 years, he was a bit of a loner in caucus.

As a politician, he’s never had to make the big saw-offs between principles and political pragmatism. Even now, he hasn’t revealed how he would: Apart from his pledge to “unleash” the oil and gas industry from climate levies and regulations and a few attention-grabbing announcements, his leadership campaign offered little detailed policy.

Certainly, he knows getting elected requires more than ideology: As a backbencher, he lobbied ministers for federal funds for a $50-million bridge in his riding to shorten constituents’ commutes.

As employment minister, the child-benefit program he promoted aggressively, which transferred tax money to parents, was very unlike his Milton Friedman principles. At the time, he said it was better than a state daycare program.

“What has evolved is my tactics,” he told The Globe. “Everything has to be compared to its alternative.

“If the question is a new government program or more personal choice, I always choose more personal choice.”

Mr. Harper shakes hands with NDP leader Tom Mulcair, as Justin Trudeau of the Liberals looks on, at a 2015 election debate in Calgary. The Conservatives would lose the election, ending nearly a decade in government.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

When the 2015 election saw the Conservatives swept of power, Mr. Poilievre also saw it as a near-death experience for his political career. His margin of victory in his Carleton riding shrank to less than 2,000 votes.

“I think he had to do a really deep think,” Mr. Majumdar said. “What does this mean next for me, personally, in my life? For my country, my party, the thing that I do?”

The political lifer stayed out of the Conservatives’ 2017 leadership race. When interim leader Rona Ambrose approached him about a shadow-cabinet post in 2016, Mr. Poilievre told her he wanted to work quietly in the background on Conservative policies for poverty and low-income earners, and he was given a lower-profile, custom-fit portfolio. And he started to work on a never-published book about economics and policy.

It’s not clear from colleagues and friends just how existential that reflection was. But at the time, people who knew Mr. Poilievre started to say he had “matured.” He was more tempered, more relaxed.

The biggest change was in his personal life. He began a relationship with Anaida Galindo, then an aide to a Conservative senator. She had emigrated from Venezuela as a child and grew up in East End Montreal.

For a man whose personal life had rarely been far from politics – the only hobby friends name is going to the gym – it was obviously life-changing. Although Mr. Poilievre has recently described big, boisterous gatherings with his in-laws, the two slipped away alone to be married in Portugal on New Year’s Eve in 2017. They became parents, to Valentina, born in 2018, and Cruz, born in 2021. For more than four years, he has been going home to family. One colleague described the change by saying Anaida “makes him normal.”

Already, Anaida is emerging as part of the political image-making – Mr. Poilievre’s first reaction to being declared leader was a Hollywood kiss with his wife, and the first words were her introduction of her husband. They brought their son, Cruz, to mark his first birthday at his first Conservative caucus meeting as leader, with reporters and TV cameras in attendance.

But there is a public Pierre, and a private Pierre, and the latter only shows himself in glimpses. Friends don’t really describe his emotional life, or detail how he grappled with big life moments. He isn’t emotive, one said. The inner Pierre stays inside.

It’s not clear if it is family life that altered some of Mr. Poilievre’s social politics. The explanation he gave to La Presse in 2020 for becoming a supporter of gay marriage was that, like many others, he had learned a lot over time. He has said less about how his stand on abortion – as a rookie MP he was anti-abortion – has changed. In 2020, he adopted the position, as Mr. Harper had before him, that he would not lead a government that legislated on abortion. This year, he said he is pro-choice.

But it is clear that in his post-2015 rethink he honed his economic ideas. The book he toyed with and the opposition work on low-income workers were followed by Commons speeches that previewed his leadership campaign rhetoric about gatekeepers. After then-leader Andrew Scheer appointed him as the party’s finance critic in 2017, his aggressive interrogations started to go viral on social media.

The Poilievres blow out a candle to celebrate son Cruz's first birthday at Sept. 12's Conservative caucus meeting, Mr. Poilievre's first since winning the leadership.DAVE CHAN/AFP via Getty Images

If vaccine mandates and truckers’ convoys lit the fire for Mr. Poilievre’s leadership campaign, it was almost kismet that a politician inspired by Milton Friedman’s ideas about freedom was given an opportunity to use the economist’s big issue – inflation – as the fuel.

You can find Mr. Friedman’s borrowed phrases in the 10-minute video about money that Mr. Poilievre posted in January, and in his simple explanation for inflation: that Liberal spending led the Bank of Canada to print money, devaluing the currency, and causing prices to rise.

Forget for a moment that it’s inaccurate to describe the Bank of Canada’s quantitative easing, which expanded the money supply but not the amount of cash, as “printing money.”

It’s more relevant that the goal of quantitative easing was to prevent the pandemic economy from teetering into recession, and that in 2020 even Mr. Poilievre described the big pandemic benefits and job subsidies as necessary. McGill University economist Chris Ragan also noted that quantitative easing hasn’t always led to inflation.

Still, Mr. Poilievre was calling out the risk of damaging inflation in early 2021, and seven months later, needling Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem as the central bank played down inflation as “transitory.” Mr. Poilievre’s pledge to fire Mr. Macklem has raised concerns about the central bank’s independence. But it is also Mr. Poilievre’s way of reminding people that his warnings were ahead of the curve.

Behind the warnings, however, he expresses surprising skepticism that central banks will resist pressure to devalue money unless they are barred from doing so – raising questions of whether, if in power, he would shackle the Bank of Canada’s capacity to counter a recession.

A sign advertises a Bitcoin teller machine in Halifax in 2020.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press

His suggestion back in March that cryptocurrency could protect Canadians against inflation appeared to reflect his anti-government instinct: favouring decentralized blockchain tokens over state currency. At least, that’s the way it sounded before cryptocurrencies crashed in April.

The crypto flirtation was at least partly political marketing to potential supporters for a politician who had an online presence that intertwined his audience with crypto bros, pandemic protesters and YouTubers.

He had slipped the bounds of political news pages and become a social-media star, with hashtags like #Justinflation as catchphrases. In 2021, his Twitter following grew by 50 per cent. In 2022, it has more than doubled to 430,000 followers.

It was Mr. Poilievre himself who built his online brand, asking colleagues for tips, and emulating hot-button tweets. One that garnered tens of thousands of responses was his November, 2021, petition to stop the “great reset,” referring to a World Economic Forum book that conspiracy theorists see as 84-year-old WEF founder Klaus Schwab’s blueprint for using the pandemic to take over the world, ostensibly with acolytes including Mr. Trudeau.

By then, Mr. Poilievre arguably had more profile than Conservative leader Erin O’Toole, who had shuffled the polarizing MP out of the finance critic’s job months before the 2021 election, then back in after it. And Mr. Poilievre was clearly putting himself in the window for a potential leadership race.

In January, when Mr. O’Toole’s leadership was on the ropes, it was a lot of the old Reform and Canadian Alliance interns, such as Mr. Scheer and Ms. Stubbs, leading the charge. Mr. O’Toole’s most intractable critics told fellow MPs that if they didn’t oust him, the internal battle would continue.

The convoy was the watershed. The spread of the Omicron COVID-19 variant had shifted the politics of vaccine mandates, and lockdown frustrations were high. Mr. Poilievre started railing against vaccine mandates for cross-border truckers. And as the convoy rolled toward Ottawa, Mr. Poilievre posted a Twitter video framing it as a broader freedom protest against Mr. Trudeau’s government and its economic record.

Four days later, Mr. O’Toole was out. Three days after that, Mr. Poilievre was in the race to succeed him.

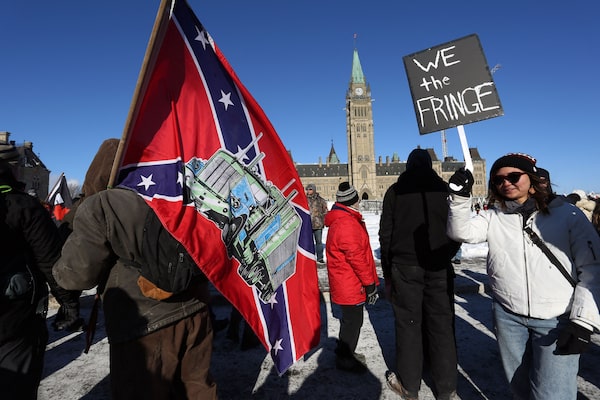

A convoy supporter carries a Confederate flag on Parliament Hill this past Jan. 29.DAVE CHAN/AFP via Getty Images

Now that he is Conservative Leader, don’t expect him to disavow his connections to convoys. He makes it a point of pride not to be seen conceding.

But people around him predict those pandemic-protest issues will recede from the news, and Mr. Poilievre will be left with meat-and-potatoes issues of inflation and affordability and the lingering feeling of visceral public frustration with Justin Trudeau.

His viral-video reach makes him a new kind of opponent for Mr. Trudeau, though the Conservative Leader doesn’t yet have the celebrity on the scale of the Prime Minister. An Ipsos online poll of 1,001 adults conducted in late August found 42 per cent didn’t know enough abut Mr. Poilievre to form an opinion.

His leadership campaign themes of scrapping the carbon tax and freeing the oil industry from climate policies, controlling spending and cutting taxes, and fighting inflation, sat alongside culture-war pledges such as defunding the CBC. He promised to cut infrastructure funding for cities that are slow to approve residential building. But his campaign was light on policy specifics. He said little about how he’d deal with inflation now that it is here. His tax plank left details to a future task force.

Mr. Poilievre has changed over time, from the smug 25-year-old MP to the 43-year-old father of young children whose manner has tempered. One veteran Conservative acknowledged it by saying he’s no longer the Pierre they wanted to punch in the face.

But the thing about Pierre Poilievre is that the lifelong political performer has been so remarkably consistent over time that it can be hard to figure precisely how and how much he has changed. “Pierre has always been a version of himself,” Mr. Teneycke said.

Mr. Poilievre is driven, combative and a calculated communicator. He has for decades criticized lukewarm conservatives. His goal is moving the public to the right, not moving the party to the centre.

He is a lifelong proselytizer, and the mission has always been both his small-government cause and his political ambition.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article mistakenly said Jenni Byrne was present at a 2008 cabinet meeting where Stephen Harper rebuked Mr. Poilievre for his remarks on residential schools. This version has been corrected.

Poilievre’s Conservatives: More from The Globe and Mail

The Decibel

After Pierre Poilievre’s leadership win, columnists Robyn Urback and John Ibbitson joined The Decibel’s Menaka Raman-Wilms for a special Twitter conversation analyzing the outcome. Subscribe for more episodes.

Commentary

Robyn Urback: Poilievre’s path to a broader Conservative tent runs through the 905

Jen Gerson: Poilievre’s win is the death knell of moderate conservatism in Canada

Andrew Coyne: It’s the Poilievre party now: completely different, and yet completely the same

John Ibbitson: In the world of politics, Pierre Poilievre has got it

Campbell Clark

Campbell Clark