"Employment is up by one million since the recession ended."

A statement like this may, indeed, be a big talking point when Statistics Canada releases the results of its monthly Labour Force Survey on Friday.

While a million more people at work sounds like a lot, the Canadian

population has also increased by roughly the same amount. The result: The

fraction of Canadians working has been pretty well unchanged for the past five

years, and has yet to return to the rates seen before the recession.

A million is a big number, but it’s not enough to signal a complete recovery from the recession.

If the past is any guide, the Statistics Canada press release will lead with a picture that looks something like this:

This gives the impression of very strong growth, with all the jobs lost during the recession recovered by 2011, and many more added since.

A picture of this sort must be what Canada’s Minister of Finance, Jim Flaherty had in mind when he recently wrote: “Since July, 2009, employment has increased by over one million – the strongest job growth in the G7. Canada’s economic growth has been the strongest among G7 countries – significantly above pre-recession levels.”

And it would appear this impressive employment growth is good reason to shift public policy priorities from job creation to balancing government budgets, and even striving for surpluses.

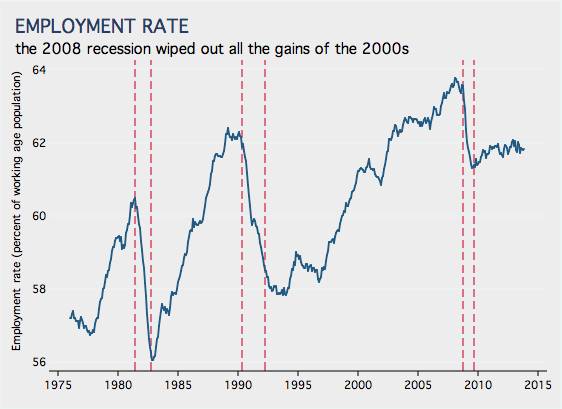

But if these same numbers are expressed as a fraction of the working-age population, then the same picture looks like this:

From this perspective, employment growth has not been particularly robust, barely keeping up with population growth and with no suggestion of bouncing back. Employment growth during the past five years has been roughly equivalent to the number of immigrants that have entered the country over the same period.

Indeed, the recent economic recovery is no more notable than the recovery from the previous recession in the early to mid-1990s, and weaker than that from the recession of the early 1980s.

Since there is little sign that current rates of employment and unemployment are generating general increases in wage and price inflation, then it would seem that a full recovery from the great recession has yet to be made.

Even if the employment level is easier to communicate and has more resonance because it draws our attention to the lives of actual people, on its own it doesn't tell macro-economists if the economy has reached its full potential. It offers no indication of whether it is time to turn the corner from promoting job growth to putting a break on it by running surpluses.

“Employment in Canada is up by a million” is hardly enough.

Miles Corak is a professor of economics at the University of Ottawa, and a visiting scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation during the 2013-14 academic year. You can follow him on Twitter @MilesCorak, and read his blog at milescorak.com.