Alberta’s oil-sands producers need to take urgent action to reduce the sector’s damaging impact on the environment by speeding the adoption of expensive and often risky emerging technologies.

That’s the conclusion of a report to be released Thursday from the Council of Canadian Academies which was asked by the Harper government to assess how technology could reduce the environmental impact of oil-sands production that is projected to more than double by 2030.

In the report, the expert panel said there are no silver bullets for reducing the significant threat that the oil sands pose to local water, land and air, or for lowering greenhouse-gas emissions that are about 20 per cent higher per barrel relative to conventional crude oil.

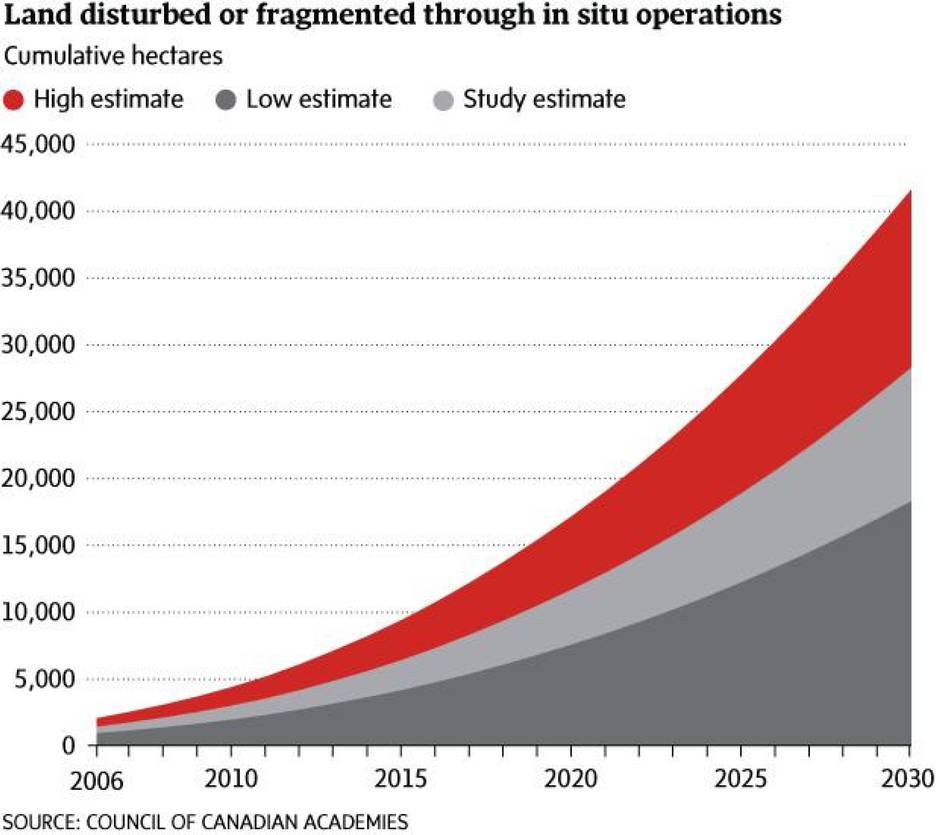

But opportunities exist for making dramatic improvements, panel members wrote, through a range of new technologies that can be applied to lowering both the carbon and water intensity of bitumen extraction as well as lightening the effect of the process on the landscape.

“We need to develop this resource in a sustainable fashion,” said panel chair Eric Newell, a former CEO of Syncrude Canada Ltd. and past chancellor at the University of Alberta. “What I hope the report might do is create a sense of urgency.”

The report comes at a crucial moment for the industry, which the federal government has promoted as a key engine of the Canadian economy.

A steep drop in oil prices has put a damper on the pace of development in the short term. Companies have delayed or shelved more than a dozen major projects and Fort McMurray – once Canada’s fastest growing city – is showing signs of retrenchment. The industry is balking at the prospect of higher environmental costs.

The newly elected NDP government in Alberta has promised to place a higher priority on environmental issues than its predecessors. Premier Rachel Notley faces a number of pressing decisions on oil-sands development, including renewing and strengthening the province’s current climate regulations which now impose modest constraints on the industry’s greenhouse-gas emissions.

With efforts under way to achieve a global deal on greenhouse-gas emissions in Paris later this year, Canada will be under pressure to reduce its carbon footprint. A successful climate strategy would have to include tougher emissions standards for the oil sands.

The report, jointly requested by Environment Canada and Natural Resources Canada, suggested that a concerted effort will be required to put technologies in place that can reap the economic benefits of the oil sands while lessening the environmental fallout. Because of the lag time in implementation, the effort must ramp up now in order to achieve a significant impact in 10 years.

The report did not directly address the question of who should pay for developing technical fixes to green the oil sands, “but changing the pace of technology deployment will not occur without strong leadership, continued investment and risk-taking by all,” the authors wrote.

Billions have already been spent on research and development and on the commercialization of technologies in the oil sands, much of it led by government investments. But at a time when the world is looking to ramp down its dependence on fossil fuels, some question whether a Manhattan-Project style approach is appropriate for developing an industry that, in the end, is still about oil.

“Current technologies could go a long way to cleaning up the oil sands but the only way to reduce overall carbon emissions is to constrain expansion. We need to slow down, clean it up and transition out,” said Tzeporah Berman a Vancouver-based environmental activist who served on British Columbia’s Green Energy Task Force.

The counterargument is that the sheer scale of the oil sands and their potential economic benefits will inevitably drive continued development in a world that will still need Alberta oil for decades to come.

“Alberta is the crucible where environmental concerns, economic concerns and the fuel with which we run our civilization all collide,” said Steven Bryant, a chemical engineer who last year took up a $10-million Canada Excellence Research Chair specializing in unconventional oil at the University of Calgary.

He is working on visionary, long-term strategies, including the use of nanotechnology that might harvest the energy from the oil sands without ever needing to remove bitumen from the ground. The council report did not deal with such early-stage technology.

The report noted that two key areas where technical progress would make the greatest difference are in greenhouse-gas emissions and the tailings ponds where process-contaminated water accumulates. But while promising avenues exist, the panel found relatively few that were close to commercial implementation, Mr. Newell said.

Serious barriers are preventing their widespread adoption, including adding costs to operations that are already capital intensive, and a risk-averse culture in which operators are reluctant to try new technology.

“While we did identify a couple of areas where there’s some low-hanging fruit, a lot of that’s already been found and now we’re down to the tough challenge,” Mr. Newell added. “That why we’re saying we really need to create the innovation environment to move these things forward.”

Greenhouse gases

Rising concerns over greenhouse-gas emissions, including carbon dioxide and methane, have made the oil sands a global environmental issue.

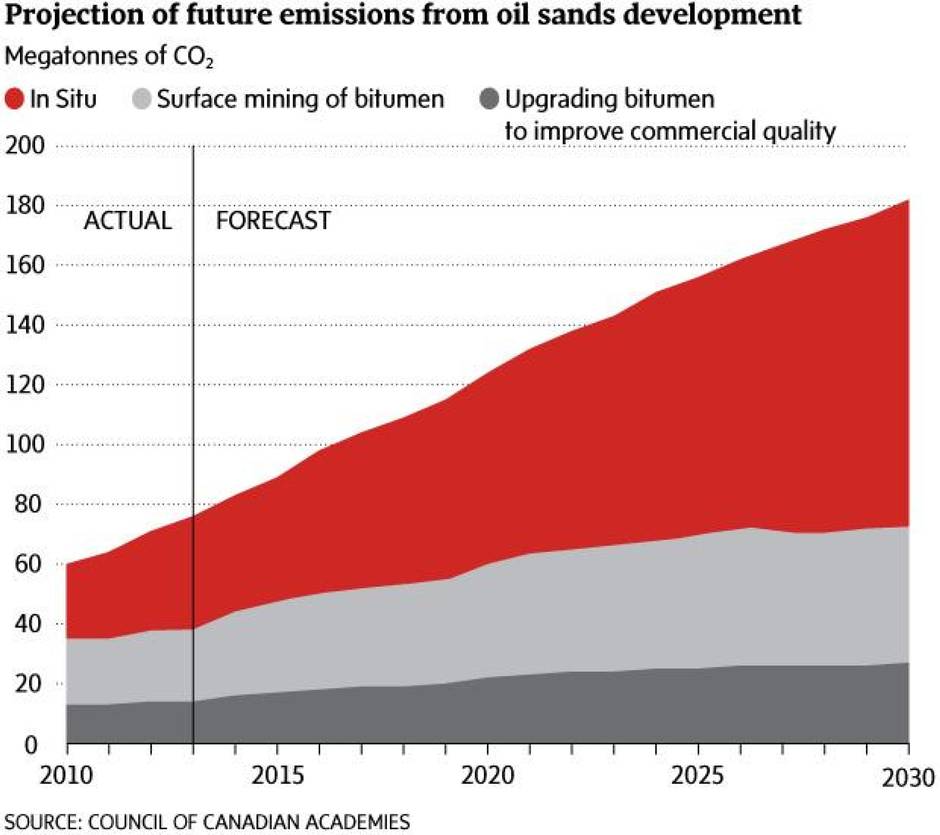

Without any change to current practices – and given current forecasts for production increases – the oil sands would generate 180 million tonnes of CO2 a year by 2030, a tripling of its 2010 level. Such an increase would make if extremely difficult for Canada to meet the commitment announced early this month by Prime Minister Stephen Harper to reduce by 2030 GHG emissions by 30 per cent from 2005 levels.

Though there is debate about its impact relative to other sources of crude, there is no question that the oil sands extraction is an energy-intensive, emissions-heavy means of producing crude, in both the mining and in situ sides of the industry.

The in situ process typically involves injecting steam underground to heat the bitumen and lower its viscosity, allowing the tar-like material to flow more easily up to the surface. The steam is created by burning natural gas – equivalent to the energy of one barrel of oil for every five barrels extracted in this way.

In the near term, the report from the Council of Canadian Academies identified the addition of gasoline-like solvents to the steam to help break up the bitumen as the most promising approach to reducing the energy intensity of the method. The more easily the bitumen is dissolved the less steam is required and the more the carbon footprint of the oil sands begins to resemble that of conventional oil.

Indeed, companies such as Cenovus Energy Inc. are already making strides in using solvents to reduce the need for steam.

Looking further ahead, members of the panel that produced the report considered alternatives to burning natural gas to power the process, including hydroelectric or small pebble-bed nuclear reactors. “That could also make a dramatic improvement in greenhouse gas emissions but the panel assessed those were at least 10 years away,” said Eric Newell, panel chair.

Tailings

Reduction of the massive tailings ponds and drying areas created by open-pit mining represents a monumental challenge for oil sands producers.

Tailings are the waste products from the process of extracting bitumen from the sands in which it is trapped. They include coarse material which is mainly sand and can be easily separated and used for diking, as well as water and smaller particles of clay and silt – or “fines” – to which residual bitumen adheres.

Alberta passed its Directive 74 regulation in 2009, requiring companies to capture 50 per cent of the fine tailings and divert them from the ponds by transporting them to dedicated drying areas. Over time, that process would reduce the need for tailings ponds.

But the industry was unable to meet Directive 74; it was rescinded this year and replaced by a “tailings management framework” that has a similar aim but for which regulations have yet to be devised. Tailings ponds cover 77 square kilometres, and the Council of Canadian Academies says that footprint will expand over the next several years as companies cope with the waste from existing and new mines along the Athabasca River.

The environmental threats include the large disturbance of land that must be reclaimed; seepage of polluted waste-water into groundwater; fugitive emissions of carcinogenic compounds from the ponds; windblown dust from drying areas that contain “chemicals of concern,” and risk of a catastrophic break in a dike that would send fluid tailings into the Athabasca.

The academy report says there is no single solution for the tailings ponds but a “silver suite” of technologies that would reduce the extent of ponds and speed up reclamation.

Syncrude, for example, is commissioning a $1.9-billion centrifuge that acts like the spin cycle on a washing machine to separate the water from the solids. The water can be recycled for reuse in the mining process, while the solids are deposited in areas that will eventually be covered with top soil and reclaimed.

Water

The extraction of bitumen from sand is a water-intensive process that poses a number of threats to the region’s ecology. They include the withdrawal of fresh water from rivers, especially in periods of low flow when ecosystems are already under stress; efforts to eventually return process-contaminated water to the environment; and potential contamination of ground water from seepage and leakage during operations.

Producers are investing heavily in water reduction and reuse, aiming to reduce to an absolute minimum the amount of fresh water withdrawn from the Athabasca and other rivers. But concerns persist.

The mining side of the business uses roughly three barrels of water for every barrel of oil produced, while the in situ producers use a third of a barrel of water for every barrel of crude. Given expansion plans, the council report forecasted that water withdrawals for mining operations will double from 2012 to 2030, to 2 billion barrels of water a year. The current use is less than 1 per cent of the water available from the Athabasca.

The producers are increasingly recycling and reusing water. Suncor Energy Inc. is even piping recycled water from its main mine site to its Firebag in situ project for its steam-assisted gravity-drainage (SAGD) operations.

Environmental groups say that’s not enough, noting Syncrude and Suncor were grandfathered under recently announced regulations and can continue to draw water from the Athabasca in periods of low flow. The river is well below its usual spring levels as dry conditions have resulted in the spread of forest fires. In a release Wednesday, several groups called on the NDP government to force the two original oil sands producers to abide by limitations of water withdrawals.

The council report also raised concerns about potential contamination of surface and ground water from seepage from tailings ponds and process-water from in situ projects. It concluded industry will have to step up its efforts to treat waste water, while the province needs to set standards that would allow industry to return the water to the rivers once it has been adequately treated.