Businesses around the world are facing a crisis of trust, including in Canada.

That’s according to the Edelman Trust Barometer, the PR firm Edelman’s annual global research study. The survey of 33,000 people in 27 countries measured trust in government, business, media, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Compared with last year, countries with overall results low enough to qualify them as “distrusters” have risen significantly, while fewer countries’ responses qualified them as “trusters.” Canada fell out of the “trusters” category this year, and now ranks as neutral. Among 1,200 people surveyed in Canada, trust in institutions on average fell to 53 per cent from 60 per cent in 2014.

Canadians’ trust in NGOs was flat compared with last year, at 67 per cent. Trust in media fell from 58 per cent to just 47 per cent. Trust in government also fell slightly, from 51 per cent to 49 per cent, and trust in business declined from 62 per cent to 47 per cent.

“In business, it was driven by the general skittishness about the economy,” said Edelman Canada chair and CEO, John Clinton. “In media, it was more scandal driven. ... The Jian Ghomeshi news broke in the middle of the study, and I think that put a lot of pressure on media.”

The most surprising change in this year’s study in Canada, Mr. Clinton said, was the sentiment of the survey respondents Edelman calls the “informed public.” That group makes up roughly 200 of the people surveyed in Canada, who are more educated, have higher incomes, and are tapped in to news and policy issues. Those people tend to respond slightly more positively in the surveys, but this year, awareness of economic issues such as dropping oil prices and employment uncertainty, in addition to other news, caused them to respond more negatively.

While trust in business generally was lower, however, Canadian companies fared well on the world stage. Asked how much they trust companies based on the location of their headquarters, people in the survey ranked Canadian-based businesses second highest at 75 per cent, behind Sweden at 76 per cent.

Marketers face an uphill battle as they attempt to wield more influence with consumers, particularly online. Canadians reported trusting “my friends and family” and “an academic expert” most when they are spending time on social networking sites. Trust in “companies I use” was relatively neutral, but information from a company’s CEO, and from “brands I don’t use” both ranked decidedly negatively.

In fact, the credibility of a CEO acting as company spokesperson fell in Canada to just 28 per cent, the lowest level since 2009.

A major focus when it comes to trust issues has to do with the pace of technological change. Slightly more than half of Canadians surveyed felt that development and change in business is moving too fast, and just 30 per cent felt that innovation is moving at the right pace. And Canadians feel that the wrong motives are driving change: business growth and greed/money were the top perceived drivers of change in business.

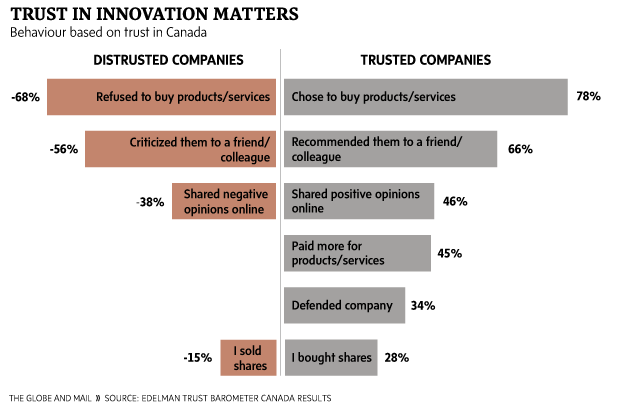

Addressing these concerns will be important for companies, since trust directly affects a brand’s image among consumers. Their opinions are important, because friends, colleagues and family are the most trusted sources of information online – a drop in trust can be infectious. Canadians reported that they took action to spread their opinions of companies this year.

And it’s not just a marketing concern: less trust leads consumers to believe an industry needs more oversight.

“Innovation has been the go-to, to build business. ... Canadians are saying, ‘You’re giving me new things too fast,’” Mr. Clinton said. “...When personal greed is seen as the number-two thing [driving change], you’ve got a challenge.”