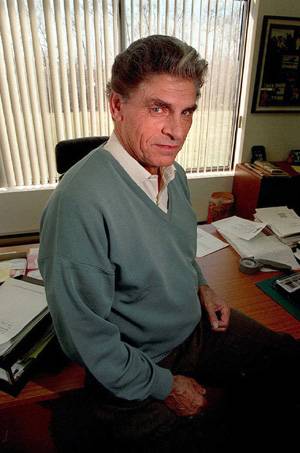

THOMAS FRICKE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The name of his company should be familiar to anyone who watched late-night television in the 1960s or 1970s and succumbed to the impulse to purchase a lint brush, vegetable slicer or greatest-hits record.

Philip Kives, the Saskatchewan farm boy who became a successful merchandise executive and trailblazing TV promoter for his company, K-tel, has died in Winnipeg. He was 87.

The K-tel supercut: Highlights of their zaniest TV commercials

1:01

Starting at the age of 8, when he would auction the fur of weasels he caught on his trap line, Mr. Kives spent his life refining his sales skills, hawking small appliances door-to-door, making pitches on the Atlantic City boardwalk and harnessing the power of the airwaves.

Relatives and employees at his company confirmed Mr. Kives died Wednesday but did not provide further details.

Mr. Kives was one of the iconic business figures of Winnipeg, alongside Izzy Asper and the Richardson family, said Allan Levine, a historian who is married to a cousin of Mr. Kives and has written about him.

"It's a classic rags-to-riches [story]. … He certainly grasped the powers of TV advertising."

Mr. Levine said that in person, Mr. Kives was soft-spoken, genial family man.

His ads, however, were flamboyant, injected with a high-energy chutzpah that made them hard to ignore, delivered at a bouncy, staccato pace that almost felt as if exclamation points filled the air.

Among the products he touted were the famous $9.95 Veg-O-Matic manual food processor ("Dial from slice to dice! Fast and easy!") …

… the $2.99 Brush-O-Matic ("Ideal for old suedes, woolens, hats and all other clothes!");

… and the bottle cutter that turned empties into tumblers and vases ("So stop littering! Save those empty bottles! They're valuable. Get K-tel's bottle cutter kit now! Only 3.99!").

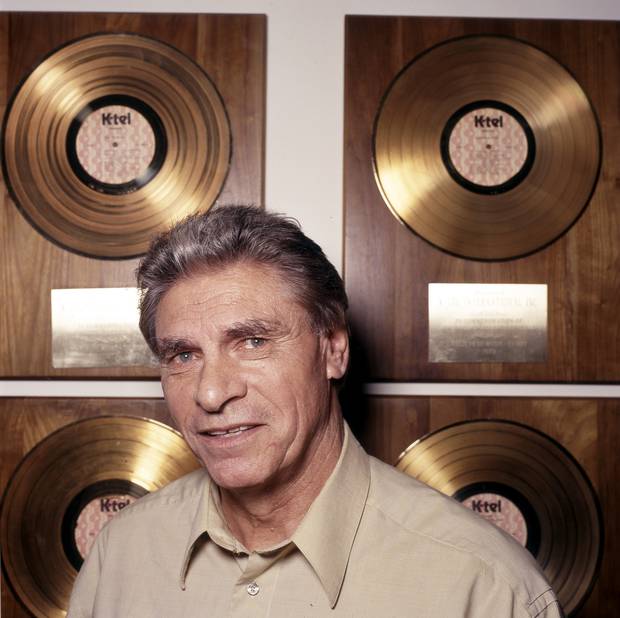

K-tel also offered music compilation albums ("Original Hits! Original Stars!") ranging from classical music to "24 Great Tear Jerkers – a super collection of the greatest love songs of the 50s and 60s."

Those ads set the tone for later generations of infomercials and direct-merchandising pitchmen and would be parodied by the likes of Dan Aykroyd – who had a skit on Saturday Night Live in which he played a salesman for a fish-shredding blender called the Super Bass-O-Matic – and on an episode of The Simpsons, in which the fictional B-movie actor Troy McClure promotes widgets on a show called I Can't Believe They Invented It!

A key to Mr. Kives's success was the way he adapted to changes in technology, Mr. Levine noted.

He flogged sewing machines and vacuum cleaners in country towns just as rural areas were getting electricity in the 1950s. He figured out how TV commercials worked as the medium established its dominance in the 1960s. After a period of setbacks in the 1980s, when he diversified too much and ran into trouble with banks, Mr. Kives rebounded and adapted to the Internet age by selling the digital rights to thousands of songs and ring tones.

The third of the four children of Kiva Kives and the former Lily Wiener, he was born in Oungre, Sask., on Feb. 12, 1929.

The family was originally from Romania but had emigrated to Turkey, where his two elder siblings were born, before moving to Canada in 1926 and settling in mid-winter on a farm in Saskatchewan's Weyburn district.

In a biography page on his company's website, Mr. Kives recalled the hardships of growing up in the Dust Bowl era, when farmers were beset by drought and the Great Depression of the 1930s.

"We had no power or running water. I recall the difficulties of hauling drinking water over four miles, as there was always a shortage. I remember milking cows daily from the age of 5 and helping my family churn the milk by hand," Mr. Kives wrote.

After high school, he tried to leave the family farm for Winnipeg, taking odd jobs.

"I did not enjoy farming," he told Canadian Business magazine in 2006.

"We had very poor land out there. I looked around at how people were living and I thought, I'm going to have a tough time living on a farm for the rest of my life."

By 1957, he had moved permanently to Winnipeg and became a successful travelling salesman, making $29,000 a year – 29 times what he earned on the farm.

The trick to selling door-to-door, he told Canadian Business, was that "you always ask a positive question so customers can only answer one way: yes. You say, 'You would like your wife to have this, wouldn't you?' And he'll say yes."

By 1961, he and his younger brother, Ted, were demonstrating pots, pans and knives on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, next to Ed McMahon, the future sidekick to Johnny Carson, who was touting blenders and vegetable slicers.

"You fought for a living there because your competition was so tough," Mr. Kives recalled in a 1986 interview with The Globe and Mail. "It was a place where the strong survived and the weak died. After that experience, I was well aware that nobody was about to give me a break or anything for nothing."

Back in Winnipeg, he realized that he could reach more people through TV.

He did a live five-minute commercial for a non-stick frying pan. By his own admission, the product wasn't good. But the great sales following the commercial confirmed his hunch.

At first, he sold gadgets made by a New Jersey inventor, Samuel Popeil, whose creations included the Veg-O-Matic, the Pocket Fisherman (a folding rod and reel) and the Feather-Touch Knife.

Mr. Kives wrote the scripts himself and explained to Canadian Business magazine how he made his pitch: "In the first line, I always tell the consumer what I'm selling. Tell them what you've got upfront. Don't keep them guessing."

In one famous episode, Mr. Kives set up shop in an Australian hotel in 1965 and started promoting the Feather-Touch Knife on local TV.

"I was working the Calgary Stampede. I met someone from Australia and the next thing you know I was on a plane to Australia. … I went to Australia and I sold a million knives in five months and I made a dollar a knife," he told The Globe and Mail.

He said that Mr. Popeil ended their partnership later that year because he felt Mr. Kives was getting "too big."

Mr. Kives started developing his own products and branched out into the record business, pumping out compilation albums for every musical style from polka to disco.

The secret to those albums, he told the Chicago Tribune, was to convince aging stars to re-record their past hits, enabling him to circumvent the big record companies who owned the original rights to the songs.

His wealth enabled him to acquire a stable of 30 thoroughbred horses, and he established a solid reputation as a breeder of champions. But otherwise his tastes remained frugal, according to a Globe and Mail profile in 2000, which noted that his house was a modest bungalow, his car a "slightly beaten-up, grey Cadillac sedan" and his fine-dining choice a franchise steakhouse.

By the early 1980s, his company had expanded into oil and gas exploration, financing a feature film, real estate, ownership of the Viscount Gort hotel in Winnipeg.

However, worried about K-tel's performance, in 1984, four U.S. banks called in loans totalling $10.5-million (U.S.), forcing the company to apply for bankruptcy protection. The next year, the Bank of Montreal placed K-tel's Canadian operations into receivership.

"A verbal deal is no good with a banker even if you have had lunch with him for 20 years," he complained in a Globe and Mail interview.

The turmoil also forced the ouster of two of his cousins from their jobs as top executives of K-tel, who then set up a rival company, R-Tek Corp.

Mr. Kives eventually reorganized his company and went back to selling his products to a new generation of TV viewers.

In 2004, three years after he had stopped working, he came out of retirement to negotiate a deal with Apple, licensing his music catalogue.

"I knew we would emerge from trouble because I am a scrambler and a survivor. I thrive under pressure and become stronger," he once told The Globe and Mail.

Mr. Kives leaves a brother, George; his wife, Ellie; and children, Samantha, Kelly and Daniel.