Road block

As Toronto city council adjourned for lunch earlier this month, dozens of people gathered outside City Hall with large signs, cheering and chanting. “Make our voices here heard at City Hall,” shouted the man at the centre of the horde, Ian Black. “We need city councillors to hear the message.”

The scene, captured by dozens of TV news cameras, could have easily been mistaken for a political protest, like the one just a few metres away against council’s recognition of the anniversary of the Armenian genocide.

But this wasn’t a typical protest, and Mr. Black no political organizer. Instead, it was a rally staged by Silicon Valley-based tech company Uber to drum up support for their local ride-sharing service. “Uber’s here to stay! Uber’s here to stay!” Mr. Black, the company’s manager in Toronto, shouted.

At least one passerby did a double-take, remarking to a reporter how strange it seemed for a company valued at more than $40-billion to be staging a protest. But Uber has held similar rallies all over the world, and to view the event as a local battle – against city staff, who have waged a court case set to be heard next week to shut them down, or councillors who struggle with regulating them amidst the quagmire of taxi licensing – is missing the point.

For Uber, which launched in 2010, it’s about building a global movement. And to meet this ambitious goal, the company knows, requires something beyond the usual marketing tactics. It requires a campaign on a larger scale, a campaign that suggests more is at stake than the survival of an app.

One year ago, Uber – the scrappy tech company that enables anyone with a smartphone to hail a car or turn theirs into a private taxi – was facing a public-relations crisis.

Questions were mounting about the company’s safety policies, after a string of alleged sex assaults on passengers. Just last month, a Mississauga Uber driver was charged with sex assault on a passenger. And brash comments from senior executives – most notably CEO Travis Kalanick – landed the company in one controversy after another. Meanwhile, the company’s modus operandi of operating with little regard for local regulations, resulted in a growing list of legal troubles.

Through aggressive expansion, the company had quickly become one of the giants of Silicon Valley. But its public persona had not matured beyond that of a bunch of arrogant frat boys who would publicly muse about hiring investigators to do “opposition research” on critical journalists – as one Uber executive reportedly did last year.

So, in August of last year, they hired David Plouffe, the mastermind behind Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, to oversee communications. His role has since shifted to chief advisor and board member at Uber.

“What I’ve come to realize is that this controversy exists because we are in the middle of a political campaign and it turns out the candidate is Uber,” Mr. Kalanick wrote in an August, 2014 blog post announcing the hire. “Uber has been in a campaign but hasn’t been running one. That is changing now.”

Since then, the company has worked to present a kinder – less combative – face to the world in stark contrast to the sometimes aggressive lobbying tactics by Toronto’s taxicab industry.

They delivered puppies to offices. Held “women partner appreciation” events. Teamed up with charities to raise money for the homeless. And in interviews, Uber spokespeople used a remarkably similar, agreeable speaking style – responding to questions with “Great question,” or “Absolutely. I’m happy to explain that.”

At City Hall, the company won over Mayor John Tory, who has been a vocal supporter of Uber and similar technologies, describing the current taxi industry as “self-interested,” and in need of modernization. Meanwhile, a three-year anniversary party held at Uber’s Toronto office in February was attended by Tim Hudak and John Baird.

Around the world, the company dispatched its local leaders – referred to as “general managers,” to fit with the company’s anti-corporate image – on speaking tours.

In Toronto, Mr. Black, a Newfoundlander who, like many other Uber managers, cut his teeth as a consultant with Bain & Company, gave one such speech to the Canadian Club in December. There, Mr. Black acknowledged “missteps” the company had made in the past, and spoke of the need to become “more humble.”

“I think there was a time at our organization where we just wanted to run an app in a city that people love, and we thought about that as the extent of our responsibility,” said Andrew MacDonald, an Uber regional manager who oversees its Canadian operations. As the company grew, he said, it’s become more involved with the cities it operates in – and also learned how to better communicate this to the public.

That kind of “naivete” follows the “traditional tech marketing approach,” says Markus Giesler, a Schulich School of Business marketing professor who has spent years studying Uber. Many tech start-ups, Mr. Giesler said, pay little or no attention to public relations early on, believing simply that the public will automatically recognize new tech as better.

Through its campaign, Uber has tried to suggest that they are not merely amplifying a message, but championing a cause – framing their plight as a fight against bureaucracy and taxi cartels, against those who would stifle modernization and innovation. “Change you can believe in” – for Uber.

“David [Plouffe] cut his teeth by scaling political campaigns and helping real people get involved in the democratic process,“ Mr. MacDonald said. “We want everyone to be a part of this movement.”

By attaching their company to larger values – freedom, innovation, fairness – Uber is attempting to follow in the footsteps of brands like Apple, to appeal to people’s emotions. In this case, Uber is trying to appeal to people’s “deep-seated belief that [allowing Uber to operate is] morally the right thing to do,” Mr. Giesler said.

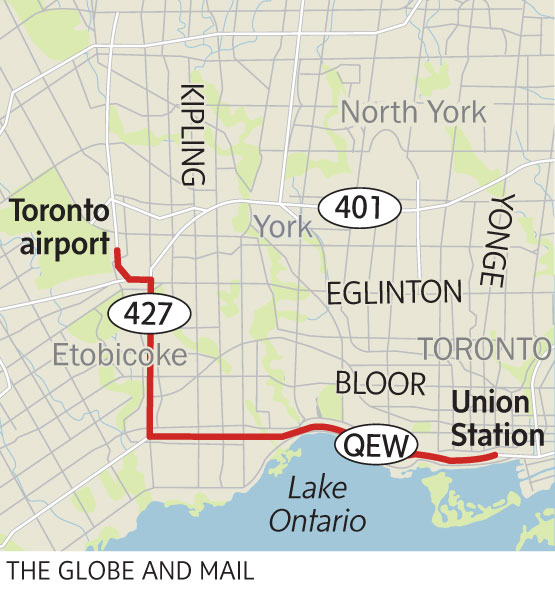

If it all seems like a bit much coming from a taxi company, that’s because Uber’s ambitions don’t end at ride-sharing. The company, which now operates in 58 countries, has plans to expand to a variety of services. Earlier this month, Uber Toronto introduced a food-delivery service. In the U.S., they run a courier service, and deliver toiletries and other drugstore items – programs that Mr. Black said could be introduced in Toronto in the future.

But first, they’ll have to win over the hearts and minds of Toronto residents, and hope those residents in turn will lean on lawmakers. Judging by the attendance of the rally that afternoon – attended by only a few dozen people – they still have a ways to go.

“In order for their innovation to succeed, they need to not just have a great product, they need to have the right society – a society that is accepting of certain changes,” Mr. Giesler said.

“This is a matter of economic survival for Uber.”

Uber across Canada...

Ottawa

Ottawa has been cracking down on UberX drivers since October, despite high-profile support at the time from John Baird, then the minister responsible for the National Capital Region. Since then, 24 drivers have pleaded guilty to 42 by-law charges in relation to operating unlicensed cabs, the city says, with fines totalling more than $16,000.

Ottawa city council is about to start a review of taxi licensing – including looking at “emerging technologies,” says councillor Diane Deans, chair of the committee that oversees the bylaws.

-Chris Hannay

Montreal

In Montreal, Uber’s future is clouded. The Quebec government has declared the service illegal and has given powers to inspectors affiliated with the province’s vehicle licensing agency to stop and seize Uber cars. Revenue Quebec raided Uber’s offices on suspicion the company violated tax laws. And Montreal’s taxi industry has mounted vigorous protests, even creating its own group of vigilantes to sniff out taxi drivers working for Uber on the side.

But the company is betting that Quebec will do for Uber what it is planning to do for Airbnb – namely, regulate the service by taxing it and imposing other fees its rivals pay. Other jurisdictions have legitimized Uber by bringing it into the legal framework, including the Philippines. “When innovation comes to a market, regulation follows,” said Uber Quebec’s general manager Jean-Nicolas Guillemette. “It’s never the other way around.”

-Nicolas Van Praet

Edmonton

Last fall, Edmonton city council voted to look at drafting new bylaws to include regulations for ride-sharing apps like Uber – but with the condition that Uber suspend its operations in the meantime.

Uber did not comply, and as a result, the City of Edmonton is seeking a permanent injunction against the company. Still, city staff is expected to deliver its report in the fall on potential new ride-sharing rules for companies such as Uber.

-Ann Hui

Calgary

Calgary has been working with Uber, and the company’s limo-style service should hit the city’s roads soon. But UberX is a long way from meeting Mayor Naheed Nenshi’s standards.

“I don’t mind innovation. I don’t mind new entrants. But as a regulator, my number one job is to preserve people’s safety,” he said in an interview in May. “When it comes to UberX, there are some very serious safety concerns that we continue to have.”

A driver’s personal car insurance, he said, is not enough. He wants commercial insurance so if a driver, for example, hits someone, the injured person has legal recourse. Mr. Nenshi has met with the Insurance Bureau of Canada, with Uber on the agenda.

-Carrie Tait

Vancouver

Mayor Gregor Robertson says he has been concerned about “problems” that Uber might create so there’s a moratorium on the company’s service while his administration takes a closer look at the future of cabs, Uber and other transportation.

During an unrelated news conference on Thursday, Mr. Robertson defined “problems” as taxi-industry concerns about the lack of regulation for Uber and his concern about whether Uber would meet standards imposed on taxis.

Uber operated its Ube Black service in Vancouver for about six months in 2012, but withdrew from British Columbia after the provincial transportation regulator imposed a minimum $75 fare per trip. Uber officials have said they want to return to Vancouver.

“There’s still work to do,” said Mr. Robertson, noting the province also has its concerns about Uber. “We’re hoping with all parties at the table, we can find a find a solution here that gets better service here in the region, and for Vancouver specifically, but keeps the standards very high.”

--Ian Bailey

...and around the world

New York City

Yellow cabs in New York sued the city in March for allowing Uber drivers to pick up passengers ordering rides through the company’s app. In New York, only yellow taxis with valid medallions may be hailed for rides. The cab drivers allege that allowing Uber users to hail cabs via the Uber app violates this law, even though rides are flagged online rather than from the street.

Portland, Ore.

In February, Uber said it had discovered a security breach that allowed someone to gain access to thousands of drivers’ names and licence numbers. While the hack was discovered in September 2014, the company waited several months to disclose what happened. In response, an Uber driver in Portland launched a class action lawsuit claiming Uber had not done enough to protect their employees’ personal information.

California

The California chapter of the National Institute for the Blind filed a lawsuit against Uber in September 2014, claiming they were aware of more than 30 instances where blind customers with service dogs were refused rides. In one case, they alleged that an UberX driver put a passenger’s dog in the trunk, and wouldn’t pull over when the customer objected. The lawsuit says refusing service to blind customers is against the Americans with Disabilities Act.

San Francisco

An Uber driver in San Francisco was charged with manslaughter after he hit a family in a crosswalk, killing six-year-old Sofia Liu. The girl’s mother alleges she saw the driver looking at his cell phone before the collision, and the girl’s family sued Uber, claiming the company has some responsibility for her death. Uber has said the driver was not carrying an Uber fare at the time, so the company’s insurance policy should not cover damages or any medical bills.

Sydney, Australia

As a dangerous situation unfolded in December 2014, when a gunman took customers and staff hostage in a Sydney cafe, Uber activated surge pricing for cab rides in the area. Fares skyrocketed for people ordering rides to flee the scene. Uber claims that surge rates incentivize drivers to pick people up during periods of high demand, but after taking heavy criticism for their reaction in this case, the company offered refunds to anyone who had taken a ride out of the area.

India

A woman in India sued Uber in January for failing to ensure passenger safety after alleging that an Uber driver took her to a secluded area and sexually assaulted her. The company was banned in Delhi in December 2014 for failing to screen drivers properly, but the company returned in 2015 with promises for new safety features.

Europe

UberPop, the European version of UberX, a service that enables regular drivers – and not licensed taxi drivers – to operate their own cars as private taxis, was outlawed in France in the new year based on legislation requiring drivers carrying paying passengers to have a licence and correct insurance. UberPop was also banned in Spain after a court ruling against it, and has previously been banned in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Better Business Bureau

In 2014, the U.S. Better Business Bureau gave Uber the lowest possible rating, an F, based on consumer complaints related to surge pricing. Angry customers say they aren’t properly informed about how they are charged for rides, and don’t receive support when they try to complain to Uber.