The new six-part television drama Between chronicles a town besieged by a disease that spares only the young, leaving teenagers in charge. But watch closely when it premieres next month and you might catch a glimpse of a TV world in similar turmoil.

In Canada, where it was conceived, the show will make its debut May 21 on the City network, then later on the streaming service Shomi. But American viewers can watch it the same day on Netflix, thanks to an unusual production deal.

Between straddles two worlds: The traditional TV business and the new frontier of online, on-demand video. Much of the money that made the show possible flowed through TV’s Canadian content system. But data and funding from Netflix Inc. helped shape it with tweaks to content and casting. Actor Jennette McCurdy has a huge following from the Nickelodeon shows iCarly and Sam & Cat, and Netflix helped nudge her into Between’s starring role.

“They just sort of knew there’s this following that’s craving new content of her,” said David Cormican, executive vice-president of business development and production at Don Carmody Television.

That hunger for content is accelerating a shift in the way TV is made and broadcast, with new streaming services springing up around the world. Some are digital disruptors challenging the television establishment, such as Netflix or Amazon.com’s Prime Instant Video. Others are owned by the broadcasters that have dominated the dial, such as CraveTV, Shomi or Hulu.

But this disruption may be happening faster than the industry can pivot, trapping the TV business in a dangerous cycle and threatening to sap profits. Current trends raise doubts about how the existing volume and quality of TV shows – dubbed a “Golden Age” of television by some – can be sustained by a stable of low-cost digital alternatives.

While the viewer is seizing control, dictating how and when they will watch TV, the programming they want is getting carved up between an ever-increasing number of distributors and platforms. That will make discovering and accessing new shows more complicated, and test viewers’ willingness to pay for multiple services. Meanwhile, the creators of content must hustle to find audiences and finance their projects. And as more TV subscribers shave down their services, cable and satellite revenues have flattened, with higher broadband use offsetting broadcaster losses for now.

Streaming services are investing more in original content, but they still stock their libraries with programs that were made for – and financed by – traditional TV. By conditioning viewers to demand control, choice and lower prices, they are fuelling the decline of a decades-old business model while feeding on its massive output.

“The traditional media have been, in my opinion, slow to react,” said Ira Levy, executive producer and partner at Breakthrough Entertainment, an independent Canadian producer and distributor. “But they’re trying to catch up real quick.”

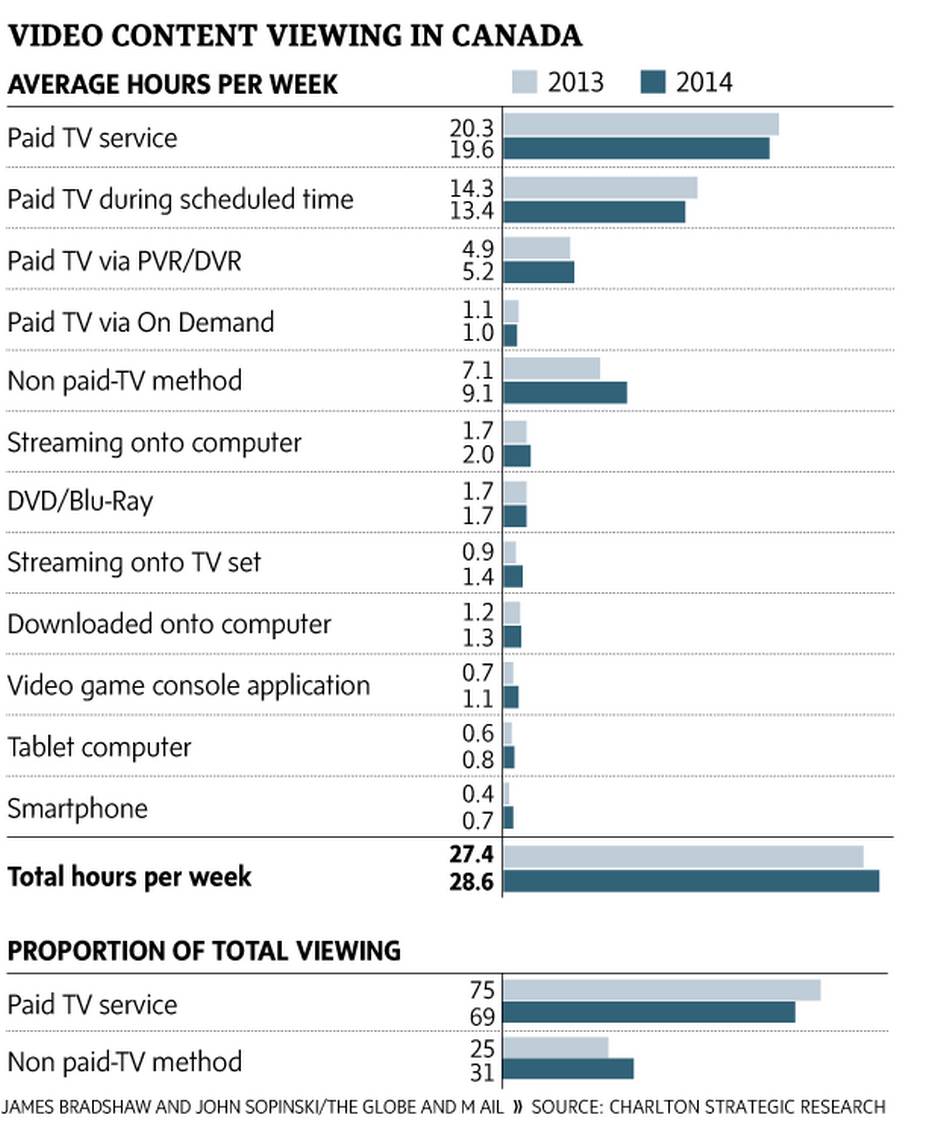

In Canada, some 69 per cent of video viewing still originated from paid TV packages in 2014, according to Charlton Strategic Research Inc. But total weekly viewing on paid streaming services like Netflix – known in the industry as subscription video on-demand services, or SVODs – spiked 37 per cent to 7.4 hours per person last year. And 18- to 24-year-olds are signing up faster than anyone.

Furthermore, for the first time, there is clear evidence that large numbers of Canadian viewers are cutting the cord on traditional TV. In 2014, there were some 240,000 more households without a paid TV package than a year earlier, a result of a mixture of customers ditching cable or satellite subscriptions and new households deciding not to buy TV packages in the first place – so-called “cord-cutters” and “cord-nevers.”

“It’s a big, big number and it ain’t going away,” said Brahm Eiley, president of Convergence Consulting Group, which studies TV subscribership trends. “If you take that out a decade, it doesn’t look very pretty for the TV business.”

Carving up a growing pie

Netflix now operates in more than 50 countries, with plans for global expansion, and its success has spurred a race to own a slice of the online space.

In Canada, the biggest broadcasters have made their move, launching Shomi, which is jointly owned by Rogers Communications Inc. and Shaw Communications Inc., and BCE Inc.’s CraveTV. The United States has Hulu and Amazon Prime, HBO Now and Sling TV, among others. The U.K. has Sky’s NowTV. Australia has Stan and Presto TV. Even YouTube plans to launch an ad-free, subscription-based service. (BCE owns 15 per cent of The Globe and Mail).

Viewers are devouring the new offerings as fast as they come online. The total volume of video being watched, including paid TV and digital, is on the rise – up 4 per cent to 28.6 hours a person, per week in Canada last year, according to Charlton Research. And programmers agree there is more high-quality content available to buy than ever. But a growing share of viewing is shifting away from paid TV.

That has broadcasters on edge and positioning their nascent streaming services as tools to stem the early signs of cord-cutting. “This is the year of the SVOD,” said Dana Landry, chief executive officer and executive director of DHX Media, a major Canadian creator and distributor of children‘s programming.

With Netflix as the established leader, there is a “land claim” under way as new streaming startups crowd into the market. At launch, a service like Shomi needs a mass catalogue of TV shows and movies to attract paying customers, and that often means stocking the cupboard with large libraries of older titles.

“They want to make sure they have an offering that’s going to work for the public, get them excited, build up the subscriber base, and then build up the data on what content is used,” said Josh Scherba, senior vice-president of distribution at DHX, which recently licensed more than 2,500 hours of its content to nine streaming services globally, including Shomi. “And then they can make some bigger bets.”

An estimated 900,000 households have tried either Shomi or CraveTV since November, according to Solutions Research Group, and two-thirds of those households also subscribe to Netflix. Shaw and Rogers want paying subscribers for their streaming services, to be sure. But for now, the data they collect about what customers watch may be far more valuable.

For decades, “the ratings were sort of the currency that everybody traded on,” said David Purdy, senior vice-president of content at Rogers, which owns networks including City, Sportsnet and FX Canada.

But Netflix and other streaming services collect vast troves of information on customers’ habits and preferences that is far more detailed: How much they watch, on which devices, what time of day, what day of the week, which genres. That can be sorted by country, city or even postal codes derived from credit card data.

Now, the holy grail for broadcasters of all types, and advertisers too, is to be able to predict what a viewer will like and recommend it to them – to engineer viewership.

“What we gain out of this is the ability to ... really draw a profile of each user, which is certainly useable across all media,” said Marni Shulman, senior director of content and programming for Shomi.

That process became even more fine-grained when Netflix introduced separate user profiles within one account, allowing it to personalize suggestions for a parent or child within one account. More than half of the site’s 62 million global users now actively use a personal profile, which has improved customer retention.

Treating this information as a precious resource, Netflix is loath to share it. But it constantly informs the company’s programming and buying decisions. Kevin Spacey’s popularity with users helped make the case for creating House of Cards, and demand for Adam Sandler comedies helped land the actor a deal making original films for Netflix, said Todd Yellin, Netflix’s vice-president of product innovation.

“No, they have not given us the secret sauce,” Don Carmody Television’s Mr. Cormican said. “But ... they’re not afraid to let you know what works for them, what works for their subscribers.”

Many TV creators now wish they knew what Netflix knows, and Mr. Cormican is hoping to get access to “glimpses” of the streaming giant’s viewership information written into future contracts so it can be used to craft other shows.

Even so, predicting viewers’ likes and dislikes is still “a mix of art and science,” Mr. Yellin said. He thinks Netflix is “good to very good” at it, “but no one is great at personalization. It’s a long journey.”

And as more streaming services come online, viewers and the shows they pay to watch are becoming increasingly scattered across a wider range of providers. Even the broadcasting giants are more comfortable Balkanizing their audiences between TV and online if it helps avoid losing them altogether. “You can see the beginnings of a real fragmentation,” said Mr. Eiley of Convergence Consulting.

Economics off kilter

The shift online has left the economics of producing and selling TV shows “all wonky right now,” as one industry insider put it.

But to grasp how the business model is changing, it helps to first understand how it has worked. Producers and broadcasters closely guard financial details for competitive reasons. But Aravinda Galappatthige, a media analyst at Canaccord Genuity Group Inc., provided The Globe and Mail with a representative example of how a fictional show – in this case, an animated children’s series – could be funded.

A typical show in this genre might cost $300,000 per half-hour episode to make.

About 60 per cent of that, or $180,000, would be covered by government tax credits, grants from the Canada Media Fund, and other benefits. But a producer is only eligible to receive those funds once it has a commissioning broadcaster on board.

Of the remaining $120,000, the commissioning broadcaster could pay $80,000 per half hour, which would give them exclusive TV rights to the show for three to five years, only in Canada. The producer then sells some equity in the show, or perhaps the territorial rights for another country to an American or European broadcaster for two or three years. In the U.S., that might be worth $30,000 per episode; in France, perhaps $10,000. An Asian market could pay just $2,000, or less. The producer might be on the hook for what’s left – perhaps $20,000 per half-hour. They produce and air the show, hoping it becomes a hit.

Years later, when those contracts expire, the rights revert back to the producer, which can resell them. But this time, they are worth less – the commissioning broadcaster might only pay $20,000 per episode to renew. Over its life, a show that does well might net a producer a 40- or 50-per-cent margin on the net cost of producing it.

Occasionally, a streaming service might buy the rights to a popular show by itself. But more often, past seasons are bundled together in packages of anywhere from 50 to 500 half-hours, for which the non-exclusive rights would cost $1,000 to $1,500 per half hour. The price for exclusivity, on TV or online, can be 10 or even 20 times the non-exclusive cost in some cases.

Television providers often pay dearly to be the first to air prime time dramas. And live programs like sports, news and awards shows have helped keep viewers loyal. But even those pillars appear threatened by the digital shift. In February, Dish Network launched Sling TV in the U.S., which lets subscribers stream networks such as CNN, the Disney Channel and sports giant ESPN for $20 (U.S.) a month.

With many more viewing options, having exclusive shows to attract viewers is even more essential. Netflix learned that lesson early and invests heavily in originals, from House of Cards to Bloodline.

But what the cord-cutters and online video evangelists often ignore, or don’t realize, is that while online video is driving more and more decisions at the negotiating table, traditional TV still pays the bills for most new shows. To date, TV revenues have held relatively firm, but there are signs an era of growth is ending.

In the U.S., where much of the content on Canadian networks is made, the paid TV industry spent $45.3-billion on content in 2014, compared with $5.6-billion doled out by online providers, according to Convergence Consulting. In Canada, the gulf is just as wide: Traditional TV pumped $3.3-billion into programming, compared with $300-million from online players.

“The core of our business model is really still driven by the [traditional TV],” said Mr. Landry of DHX.

As a result, the best shows carried by online providers are often aired after they appear on TV, carved up across multiple services, and available in some countries but not others, depending on who holds the rights. This fragmentation can frustrate viewers, and spur them to look for other options.

The piracy problem

An estimated four million Canadian customers willingly pay for Netflix. But some 22 per cent of them admit to using services that give them a U.S. IP address, allowing them to watch the more content-rich American version of Netflix by circumventing the locks that protect Canadian rights, according to Charlton Research.

This week, Netflix singled out piracy as “a considerable long-term threat.” But TV broadcasters and distributors are also taking note, and complaining more loudly that Netflix isn’t doing enough to curb the use of technologies such as virtual private networks, or VPNs, which block a user’s location so they can circumvent territorial broadcast rights. “What we’re able to pay for a show in Canada is going to be dependent on how well protected [rights] are,” said Rogers’ Mr. Purdy. “Piracy or VPNs obviously hurt our ability to pay more.”

Another 18 per cent of Canadians admit to downloading pirated content from BitTorrent sites, some of which are improving in quality. Popcorn Time, run by a loosely affiliated collective of people dispersed around the world, offers streaming of popular shows through a Netflix-like interface. And it is entirely free.

Netflix has called Popcorn Time’s rising popularity “sobering.” But Robert (Red) English – who is in his early 20s, lives in Barrie, Ont., and has become something of a spokesperson for Popcorn Time – insists the site has no plans to blow up the online streaming industry, only to change it. He describes the project as “a great way to show people what’s possible.”

When asked whether it’s piracy, he paused before replying, “it depends.”

Mr. English thinks most people are willing to pay for content, but his group has two complaints about existing streaming services: “the region locks,” which determine which content can be playing in which countries, and “the wait” between the date many shows first air and when they appear on streaming sites. he “We’re just kind of showing everybody what we can do and what the world can do, and trying to change a couple of things with the streaming services online,” he said.

Mr. English isn’t sure how sites like his affect TV’s bottom line, but “for the most part, it’s not like they’re going broke over it,” he said.

Yet country-by-country rights and exclusivity windows are still key to the ability of producers and broadcasters to make money.

“We’ve procured loans to the tune of millions of dollars and backed these loans with corporate and personal guarantees in the hopes of recouping our investment, and then some, in order to provide for our families,” said Mr. Cormican of Don Carmody Television. “When people steal content, that is revenue out of our pocket.”

Who wins, who loses?

With broadcasters, digital giants and Web-savvy youth all piling in online, the streaming wars are on. And so far there’s no obvious winner.

“Clearly, over the next 20 years, Internet TV is going to replace [traditional] TV. And so I think everyone’s scrambling to figure out, how do they do great apps?” Reed Hastings, co-founder and CEO of Netflix, said in a conference call on Wednesday. “It’s a transition into figuring out the Internet. And the way people do that is to get involved with us, with our competitors.”

Viewers are enjoying this new age of abundance, with ample new options to access sprawling libraries of content for between $5 and $20 a month. But as content is scattered more widely, it may still be expensive to find and access it, and a mass shift away from traditional TV would harm the golden goose that currently bankrolls most of the shows on streaming sites.

The digital upstarts are winning hearts and minds as well as subscribers, and gaining financial clout to invest more in programming. But their profits remain thin, if they make money at all, and they are facing their first stiff test from rival services that have copied the Netflix template and are backed by the full might of still-powerful media giants.

The largest broadcast companies have one major advantage: The have deep-seated relationships with producers and studios, and once they own the traditional TV rights to a program for network television and specialty channels, adding digital rights can be “a logical extension,” Mr. Purdy said. “Increasingly you’re having one comprehensive discussion.”

But so far, CraveTV and Shomi are still money-losers, and the broadcasters may be splitting their own audiences with services that have yet to prove they can be sustainable.

Adding to the uncertainty are major changes stemming from Let’s Talk TV, a landmark hearing that recently wrapped up at the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. The regulator is substantially changing Canadian content rules and the way TV channels are packaged, hoping to ease the digital shift, but many in the industry will still suffer in the transition.

Producers are hopeful, and have more doors to knock on, some of which are online-only. Niche programming has more places to catch on, and the thirst for exclusive content is driving up prices for high-quality series.

But as dollars drain out of the traditional TV system, many distributors are wary of taking risks, and producers must work harder to prove their programs will find an audience, while piecing together international deals on different platforms to earn their profits.

“The opportunity is really interesting, as long as you can figure out how to do it [and] not get caught in the squeezer in the transition period,” said Mr. Levy of Breakthrough Entertainment. “It’s like solving a gigantic puzzle every day.”