Sweden's property woes

It’s fascinating to watch what’s playing out in Sweden having experienced the tag team of Mark Carney and the late Jim Flaherty when it comes to frothy housing markets.

Mr. Carney, when he was Bank of Canada governor, and Mr. Flaherty, as finance minister at the time, took a double-barrel approach to cooling down hot markets.

The former, who now heads up the Bank of England, threatened several times to raise interest rates unless Canadians curbed their big appetite for mortgage and other debts.

The latter acted several times by clamping down on the rules, and the current finance minister, Bill Morneau, has similarly taken action.

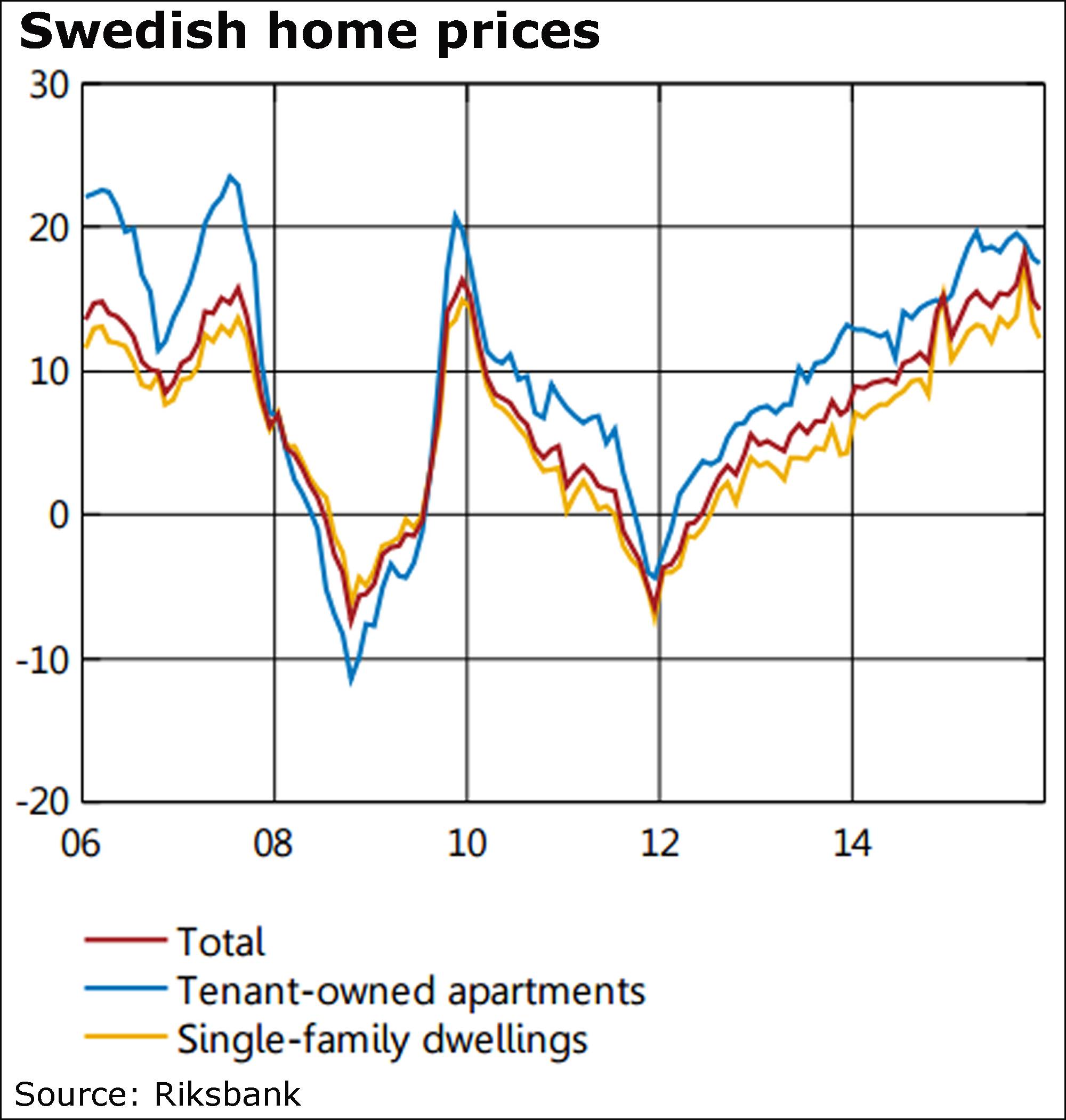

Not so in Sweden, where property values and household debt is also a big issue.

Sweden’s central bank today cut its key rate further into negative territory, admitting that low rates are fuelling both home prices and debt, which is obvious.

Not so obvious is the response of the Riksbank, which warned its government in no uncertain terms that it should act.

“If negative surprises were to occur or if rates were to increase in a way that households were not expecting, heavily indebted households may choose to rapidly increase their saving and hence reduce their consumption,” the central bank said in its monetary policy report.

“In such a scenario, an economic slowdown could be heavily exacerbated, particularly if housing prices also start of fall.”

Home prices in Sweden are rising at a double-digit pace, and the key measure of household debt to disposable income is forecast to top out at more than 190 per cent in a couple of years.

“Fundamental reforms to the housing market are needed to create a better balance between supply and demand and thereby reduce the risks associated with household indebtedness,” the Riksbank said.

“However, reforms that make households less willing to take on debt are also important, such as a gradual reduction in the tax relief on interest payments. The responsibility for such reforms lies with the Riksdag and the government.”

Not only that. It warned that it’s of the “utmost importance” that the government and the Riksdag, Sweden’s legislature, clarify the mandate of the Finansinspektionen, the financial regulator.

More measures are needed beyond those taken already, it said.

A Trump presidency?

Markets melt

Stocks are melting down this morning.

Hong Kong’s Hang Seng tumbled 3.9 per cent, while Japanese and Chinese markets were closed.

The scene is ugly in Europe: London’s FTSE 100, Germany’s DAX and the Paris CAC 40 were down by between 2.4 and 4.1 per cent, and North American markets stumbled badly.

“After a one-day respite, markets have gone back into meltdown on Thursday,” said analyst Jasper Lawler of CMC Markets in London.

“Almost every gauge of risk-taking is getting hammered lower, from U.S. Treasury yields to financial shares to the dollar-yen currency pair,” he added.

“Everybody knows the central bank-induced frenzy had to end sometime, and there are some flashing red lights saying that time could be now.”

A scene I'd love to see ...

“Sucks to be you.”

Commodity companies hit

The commodities rout is taking an ever-greater toll.

Canada’s Cenovus Inc. today cut its dividend and its planned spending for the year as it posted a hefty loss of $641-million or 77 cents a share.

Precision Drilling Corp. suspended its dividend as its fourth-quarter loss swelled to $271-million or 93 cents a share.

“The land drilling industry is almost a year and a half into a deep downturn, a result of lower commodity prices pushing customer spending down and decreasing drilling demand,” warned chief executive officer Kevin Neveau.

“There is limited visibility with few positive market signals,” he added.

“In this protracted challenging environment, financial stability is paramount for both survival and sustaining competitive advantage.”

Overseas, Rio Tinto also unveiled a dividend cut as it posted a sharply lower profit.

Manulife Financial Corp., too, was hit by energy, though it raised its dividend as fourth-quarter profit slipped.

Whither the loonie

Currency analysts at Bank of Nova Scotia believe the Canadian dollar’s “petro-currency” status may be about to weaken.

Don’t get the wrong idea. The loonie’s ties to oil will remain, but possibly weaken, according to strategists Shaun Osborne and Eric Theoret.

“Weak oil prices have been closely associated with the decline in the CAD over the past year (and more),” Mr. Osborne, the bank’s chief foreign exchange strategist, and his colleague Mr. Theoret said in a report, referring to the loonie by its symbol and to the U.S. crude benchmark, West Texas intermediate, or WTI.

“The correlation between spot and crude prices has been tight but may be nearing a point where its influence on the CAD weakens to some extent,” they added.

“This would not be unusual from an historic perspective and might reflect the evolving Canadian economic landscape.”

They noted the “phenomenon” of weak oil prices driving down the loonie, and vice versa, but also cited the fact that exceptionally high crude prices “were of no help” to the currency in 2008.

“For the CAD specifically at this point, we rather feel that the severe damage to the economy was wrought primarily by oil prices weakening below the average project breakeven for oil sands,” said Mr. Osborne and Mr. Theoret.

“Weaker oil prices are not helpful from here but will not impact the growth outlook for the economy radically,” they said.

“Moreover, there are signs that Canada’s economy is adjusting to lower oil prices.”

The loonie is weaker today, but notably still at about 71.5 cents U.S.

It’s softer because of the dip in oil, but still buoyed somewhat by the weaker U.S. dollar, said London Capital Group chief analyst Brenda Kelly.

“The CAD is losing ground but it’s in concert with other commodity currencies,” Ms. Kelly said.

“Risk aversion is gaining traction with crude oil prices continuing to take a hit.”