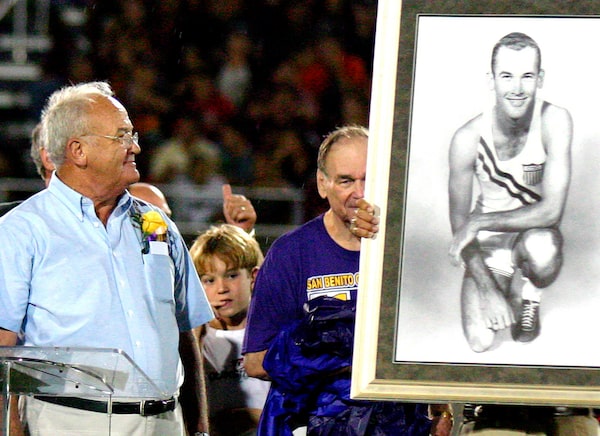

Bobby Joe Morrow, left, is honoured with an Olympic portrait of himself during the inauguration of the Bobby Morrow Stadium in San Benito, Texas, at halftime of a football game on Oct. 13, 2006.Lynn Hermosa/The Associated Press

Bobby Morrow, who sprinted to three gold medals at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia, dominating his competition as only Jesse Owens had done at the Berlin Games in 1936, died on Saturday at his home in Harlingen, Texas. He was 84.

His partner, Judy Parker, said that the cause was not known but that he had received diagnoses of anemia and neuropathy.

By the time Morrow arrived in Melbourne in November 1956, he had harnessed his speed — which he had honed chasing jackrabbits on his father’s farm in Texas — to a preternatural ability to stay calm.

“Whatever success I have had is due to being so perfectly relaxed that I can feel my jaw muscles wiggle,” he was quoted as saying by David Wallechinsky in “The Complete Book of the Olympics” (1984).

Morrow’s races took place over a week on the track at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. First he won the 100-meter sprint in 10.5 seconds, a time slowed by a headwind. (In two early heats, he had tied the Olympic record of 10.3 seconds.)

Then, in the 200-meter final, he won the gold in 20.6 seconds, matching the world record.

“Ever since I started sprinting, I wanted to duplicate the great Jesse Owens and win two Olympic championships,” Morrow said, after he had won the 100 and 200-meter races.

But he had one more race to match Owens’s 1936 feat: the 4x100-meter relay. Running the final leg after his teammates Ira Murchison, Leamon King and Thane Baker, Morrow extended the lead they had given him over the Soviet Union. Their winning time of 39.95 seconds broke the world record set by Owens, Ralph Metcalfe, Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff in 1936.

Morrow became the only Olympic runner to win the two sprints and the relay since Owens (who also won a fourth medal, in the long jump, in 1936). Only Carl Lewis, in 1984, and Usain Bolt, in 2012 and 2016, have equaled that accomplishment.

“He was a great runner, an extraordinary athlete,” Wallechinsky said of Morrow in an interview.

Morrow’s success in Melbourne propelled him into a year of national fame. He was on the covers of Life, Sport and Sports Illustrated, which named him its Sportsman of the Year. He visited the White House, appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and received the James A. Sullivan Award in 1957 as the outstanding amateur athlete in the United States.

He had hoped to defend his titles at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. But, to his frustration, he never got there.

Bobby Joe Morrow was born on Oct. 15, 1935, in San Benito, in southern Texas, and grew up on a farm nearby, outside Rangerville, where his father, Bob Floyd, raised cotton and carrots. His mother, Mattie Lucille (Danley) Morrow, was a homemaker.

Morrow’s brilliance as a high school runner attracted college recruiters from around the country. But he chose to stay in Texas, at Abilene Christian College (now a university), and became its star sprinter.

“Bobby had a fluidity of motion like nothing I’d ever seen,” Oliver Jackson, the track coach at Abilene Christian, told Sports Illustrated in 2000. “He could run a 220 with a root beer float on his head and never spill a drop.”

In 1956, Morrow won the 100- and 200-meter races at the NCAA track and field championships. He earned his trip to Melbourne with victories at the same distances during the U.S. Olympic trials.

He wanted to compete at the 1960 Olympics, even though he was becoming disillusioned with the way amateur athletics were run, at a time before Olympic athletes could earn millions of dollars.

He had to donate the $250 in prize money he won from appearing on the television game show “To Tell the Truth” to Abilene Christian. He also had to cash in plane tickets to track meets and drive instead so he had money to eat, and to refuse $500 a month for a State Department trip to South America because taking the money would have made him a professional. He went anyway, at his own expense.

His chance of making the 1960 U.S. track and field team was diminished when a groin injury kept him from competing in the Olympic trials. He was told to train with the team in the hope of going to Rome as a reserve.

On the night before the team left for Europe, he was told to come the next day to Los Angeles International Airport, where he would be told his fate. “So I met them out there and they said, ‘No, you’re not going,’” he told The Guardian in 2016. He was crestfallen.

The U.S. team did not win gold medals in any of the three events in which Morrow had won them four years earlier. The 4x100 relay team was disqualified because of an illegal baton exchange between Ray Norton and Frank Budd.

In addition to Parker, Morrow is survived by two daughters, Vicki Watson and Elizabeth Kelton; a son, Ron; two stepdaughters, Alisa Matz and Lynn Zanca; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His marriages to Jo Ann Strickland and Judy Bolus ended in divorce.

After missing out on competing in Rome, Morrow was, among other things, an insurance broker, a clothing store owner and a farmer. He returned briefly to prominence in track when he testified to the Senate Commerce Committee in 1965 that the governance of amateur athletics poorly served athletes and did not build the best possible Olympic teams.

But he faded from the track world, often forgotten when great sprinters were remembered.

“I don’t get mentioned,” he told The Guardian. “I get left out a lot. And I think that’s because I was fighting them so much.”