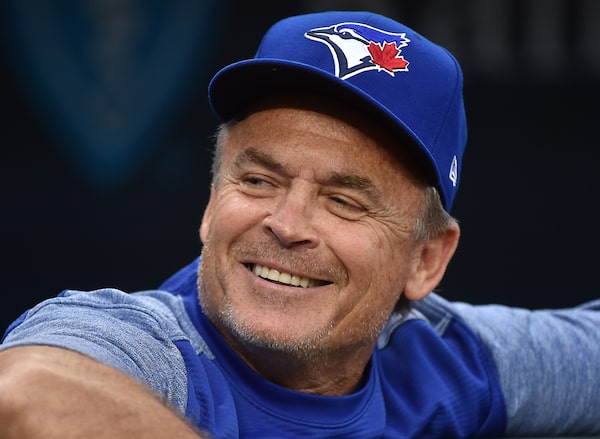

John Gibbons won’t say outright that he is being let go from his job, but takes no trouble to pretend otherwise.Ed Zurga/Getty Images

John Gibbons arrives for breakfast precisely on time in his off-hours uniform – T-shirt, blue jeans and cowboy boots.

As he sits down, a woman three tables over wearing a Blue Jays top punches her husband so hard that his menu goes flying.

Gibbons doesn’t catch it because he isn’t itching to be spotted. If some people have few airs, the Jays manager is airless. When I asked him what time we should meet, he said, “Any time. It’s not like I’m busy.”

As with most successful people who don’t take themselves seriously, Gibbons has always been a reflective guy. But not quite like this, now, at the end of this unlikely adventure.

“I am noticing things a little bit more now. I know it might be the last time I see a certain spot,” Gibbons, 56, says.

Such as?

“Like, we go to Fenway next week. You never know. I might not be back there.”

You’re never going to Boston again?

Gibbons, a "Texas forever" man, pulls back theatrically: “I’m sure not going to travel to the northeast for the hell of it.”

Gibbons won’t say outright that he is being let go from his job, but takes no trouble to pretend otherwise. The secret has been so poorly kept in recent days that he has begun speaking in past tense.

Once the season ends, the remaining year of his contract will be paid out. It’s not a firing per se, but that black swan of coach/club relationships – an amicable separation.

He has been the manager of the team for 9 1/2 years over two stints, longer and with more total wins than any man save Cito Gaston.

For a generation of fans, Gibbons is the team’s most consistent presence. Many grew up with him. He was there when Roy Halladay won his Cy Young and still there when Doc died. His soft drawl has become as much a part of the Blue Jays’ DNA as the concrete pillbox they play in.

That it finishes this way seems … unfitting. But that’s you saying it, not Gibbons.

Over the course of a meandering three-hour chat, he does not express an iota of bitterness. Not even off-the-record. There also isn’t much warmth.

“When [team president Mark Shapiro & Co.] first got over here, I thought I was gone. That’s just the way it works,” Gibbons shrugs. “Honestly, I have no complaints with the way they’ve handled things. They leave me and the coaching staff alone for the most part.”

A little reading between the lines is required here. But by the sounds of it, this is not a leave-taking between two parties who disliked each other, but rather two who never clicked. It’s a conversationless first date that lasted three years.

But Gibbons does not want to talk about things that didn’t work out. To his way of thinking, a thing that has gone wrong is something waiting to be turned right. You just have to give it a bit.

For example, how he got this job in the first place. That’s a ridiculous story that he likes telling.

Despite a lot of promise, Gibbons’s playing career didn’t amount to much. Eventually, he found himself managing the Triple-A affiliate of the New York Mets. After three years, his contract was running out and another was not on offer.

“I’d just bought a house. I had three kids. And I had a month left on my Mets contract,” Gibbons says. “I don’t know how smart that was.”

It is important to imagine that every completed thought here ends with a barking laugh. There is no one whose foolishness John Gibbons finds more amusing than John Gibbons’s.

His minor-league roommate, J.P. Ricciardi, was doing better at the time. He’d just been appointed general manager of the Blue Jays. He had two jobs on offer – third-base coach and, the lowest of the low, bullpen catcher. As it turned out, that meant there was one job on offer.

“J.P. called and said, ‘Do you want the bullpen job.’ And I said, ‘Heeeeell no I don’t.’ I went home and my wife and I are talking and she pointed out that in a couple of weeks I was going to be unemployed. So I called J.P. back.”

He had been a catcher, but hadn’t played in 15 years. The first time he got back down in a crouch was the opening workout of 2002 spring training, whereupon he immediately blew out a knee. He had no choice but to carry on.

Wouldn’t it have been better to practise that at home a bit?

“Possibly,” Gibbons says, like the punchline is writing itself.

Gibbons is rolling now. Short, staccato sentences. Hand jabbing the air. Enjoying himself. People nearby are leaning in to eavesdrop.

“The season starts. We’re brutal. I’m down there in the bullpen. We might’ve had seven, eight guys down there. It felt like there were 20 of them up a night. I had to start getting down on one knee. Honest to God, I thought there’s no way I can do this. June rolls around. J.P. fires [then manager] Buck [Martinez]. Made [then third-base coach Carlos] Tosca manager. Put me at first. Saved me. Saved my knees, at least.”

A couple of years later, he was the manager. So that’s how you get to the bigs – make a series of a questionable financial decisions and then trust to fate?

“Things just lined up,” Gibbons says, pointing ahead like he can still see that happening now. “Things have lined up my whole career in a lot of ways.”

This kind of talk is distilled Gibbons. Most modern sports managers are at pains to tell you how compulsive they are about their work. Up at 5 a.m., on the treadmill, making calls, watching tape, going at it like a penitent monk.

Grounded by his long experience on the fringes, Gibbons’s approach is more: Well, let’s see how this goes. If most of his colleagues are micro-managers, Gibbons is a macro-observer. He lets proven professionals do their jobs without fussing over them. It’s the reason he has no enemies.

He is still being paid to do a job, so he is not yet at the stage of nostalgia. But he’s inching toward it.

The single highlight of his Jays career is, he says, Game 5 of the 2015 American League Division Series, Jose Bautista and the bat flip.

“That was 22 years of frustration being let go. … That was special.”

His favourite player? Scott Rolen’s name comes up first, though there are a bunch more, few of them stars. The list includes Josh Donaldson, a player he was frequently at loggerheads with, which tells you something about both Donaldson and Gibbons.

The most gifted man you ever coached? “Vernon Wells. Everything came easy to Vernon.”

The low-light? Gibbons has to think for a while about that one.

There are a couple that leap to mind for the average fan – the clubhouse scuffle with Shea Hillenbrand, the tunnel dust-up with Ted Lilly, all those mediocre teams and mediocre years.

During his first tenure, Gibbons was portrayed in some corners as a bumptious hillbilly who’d lucked his way into the job. He often jokes about it, even now. He does so often enough that you know it still hurts him. That couldn’t have been fun.

In 2013, Alex Anthopoulos, at great personal risk, brought Gibbons back to manage a team most observers considered a mortal playoff lock. “We were horseshit,” Gibbons said. “Every once in a while, I’d say to Alex, ‘I told you hiring me was a bad idea,’”

But in terms of the nadir he settles on the first time he lost the Jays’ managing job. It was June, 2008. He didn’t see that one coming.

He was clipped in a hotel room in Pittsburgh by “three of my favourite people ever” – Ricciardi and then assistant GMs Anthopoulos and Tony LaCava.

It’s not the sacking as such that upset him, but the sense he’d disappointed people he admired.

“It was hard for me because I thought if I’d done a better job, maybe their lives might be better, too,” he says.

In the way of these things, Gibbons’s entire family was having a rare meet-up in Pittsburgh that weekend – his sons were travelling with the team, his wife and daughter were coming down from Canada.

“Normally, you’d go back to Toronto and pack your stuff. But I thought, 'We’re gonna be the Griswolds.'”

Instead of flying out, he rented a Suburban, put the whole gang in there and drove 2,500 kilometres home to Texas.

“It took us 2 1/2 days,” Gibbons said. “It’s one my best memories.”

This may be Gibbons’s greatest gift – that he is a human proton. Though allergic to the sort of "seize the day" boilerplate so common in coaching circles, he has the natural inclination to turn everything positive.

It’s the mark of a great career that you cannot reduce it to one moment, or even a series of them. It’s a feeling you gave people. After enough time and incident has passed, it becomes its own ecosystem, separate from the larger narrative.

Who defined the past five or so years of Jays’ history, the second most successful in the franchise? Bautista, Donaldson, Anthopoulos and Gibbons. Now they’ll all be gone.

It does at least seem right that, among them, Gibbons will turn out the lights on the era. Though he will never be lionized like the others, he was, to my mind, the most irreplaceable.

Gibbons was the first head coach I covered in sports. Other than getting the gig, it was the luckiest break of my writing career.

On the first day I met Gibbons, Ricciardi and a few backroom hacks were sitting with him in the manager’s office. I was brand new in the job, had absolutely no idea what was going on and was more than a little out of my depth.

As I walked in, Ricciardi, addressing the room generally rather than me in particular, said: “So this is the latest asshole from the Toronto Star?”

(After an article highlighting how the Jays tended to draft white college players at the expense of minorities, Ricciardi was not well disposed toward the paper.)

The room was a low, tight space. There were a half-dozen people wedged in there. Everyone laughed. Everyone but Gibbons. He was the only person who picked up on my discomfort, or cared.

That tendency to do the kind thing as opposed to the easy one never changed about him. He could be goaded into rage, but you had to do all the work. He could laugh at you – mocking is his default way of letting people know he likes them – but not unless he was sure you were in on the joke.

He had one ugly, blowout fight with a reporter that I ever saw. That happens.

A couple of hours later, he went to find the guy so he could apologize. That does not.

Gibbons is the finest person I’ve ever known in the game, or any other game. Gentle, forthright, funny, whip-smart, combustible, occasionally curmudgeonly and, above all, decent.

In the barstool parlance of sportswriters, he gets the highest compliment we pay any pro – he’s an adult.

You are free to take issue with his professional performance. Maybe they should’ve won in 2015. Maybe he was outcoached in the postseason the next year. That’s all perfectly debatable criticism.

But wins don’t weave a sports team, even a very good one, into a community. People do.

The players are worshipped, but distantly. You can’t empathize with them because you’ll never know what it’s like to stand in on a full count in a one-run game while 50,000 people bore their eyes into you. The players are better than the rest of us, and they know it.

Gibbons wasn’t. He didn’t try to fool people into thinking his job was rocket science. That was one of his stand

-bys: “This ain’t rocket science.”

For a generation of Blue Jays fans, he was their undercover everyman on the inside. He never lost sight of how lucky that made him.

Whereas people admired the players, they loved Gibbons. He was one of them.

The only shame in his time here is that everyone in the country who cares about baseball didn’t get the opportunity to sit with him for an hour and argue about politics or listen to him tell back-in-the-day stories.

Were that the case, he’d be Manager For Life.

In the course of the breakfast, several diners approach to get their pictures taken with Gibbons. I’ve watched this process many times with other celebrities. It’s usually a hesitant dance – the person milling uncomfortably around the edges, trying to grab eye contact and read an expression so as to ensure they will not be rebuffed and humiliated.

With Gibbons, they just walk up and start gushing. They know in their bones he won’t refuse them. That he’ll talk to them like any normal person would. That’s what he meant to the city.

“Canadians are a lot like Texans …” - an impish pause – “… I’m not trying to insult anyone. They’re hard-working people. Not a lot of BS. That’s something I’ve grown to appreciate.”

Now that it’s wrapping up, Gibbons finds himself in the same state of flux in which it began. He and his wife recently sold their house in San Antonio in anticipation of some sort of change. The lease on their apartment in Texas is up in a few weeks.

He still sees himself managing a major-league team, or at the least working in baseball. But since this time there is no urgency, he’s feels no pressure to think about whatever’s next.

“Something’s gonna line up, man,” Gibbons whoops, and a few heads turn right around. “The good Lord’s gonna intervene!”

Editor’s note: (Sept. 8, 2018) A previous version of this story alluded to a Gibbons dust-up with Al Leiter; in fact, it was with Ted Lilly.

Cathal Kelly

Cathal Kelly