In this photo provided on Aug. 31, 2020, by the Greek Defense Ministry, warships from Greece, Italy, Cyprus and France participate in a joint military exercise in the Eastern Mediterranean.The Associated Press

Greece and Turkey are on the brink of war once again – the trigger this time being access to rich reserves of natural gas under the Eastern Mediterranean.

Every decade or so, the two countries come close to blows over a disputed hunk of rock or stretch of water in the Aegean Sea and other seemingly insignificant bits of the Mediterranean. There were little skirmishes in 1987 and 1996, either of which could have turned explosive if cooler heads had not prevailed.

This time it’s different, because potentially vast reserves of gas, and perhaps oil, are at stake and every country in the region wants a piece of the action. Many are getting it, but not Turkey. The gas discoveries were supposed to unite the region’s countries, including the Palestinian Territories, and provide them with cheap energy and a steady stream of export dollars. Instead, the fight over hydrocarbon exploration rights has injected another dose of instability into an already volatile region.

On Aug. 12, a Greek frigate and a Turkish frigate collided in disputed waters between Cyprus and Crete. The Turkish ship was one of five in the Turkish fleet escorting the Oruc Reis oil and gas exploration vessel, its hull splashed in the red and white of the country’s flag. Greece said the collision was an accident; Turkey interpreted it as a deliberate provocation. “If this goes on, we will retaliate,” Turkish strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan bellowed.

Fears are high that this will escalate into an armed skirmish. Gallia Lindenstrauss, senior research fellow at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, said: “A limited conflict – I do see that as a possibility.”

A Greek oil and gas executive, whom The Globe and Mail is not identifying because he is not authorized to speak to the media, said he puts the odds of a shooting war between the two countries at 50/50.

This week, Greece said it will buy new weapons to counter the superior Turkish military threat. “The Turkish leadership is unleashing, on a near-daily basis, threats of war and makes provocative statements against Greece,” said Greek government spokesman Stelios Petsas.

Greece and its Mediterranean allies are also pushing the European Union to impose sanctions on Turkey if it does not remove its military and seismic ships from Cypriot waters.

Everyone knows the Eastern Mediterranean contains lots of gas; some of it is already being delivered by pipeline to Egypt and Israel, cutting their energy import bills and carbon footprints. History has largely sidelined Turkey. The way the maps of the territorial waters, continental shelves and exclusive economic zones (EEZs) are drawn means that Greece and its ally the Republic of Cyprus have the greatest access to the subsea spoils in the Aegean and huge swaths of the Levantine Sea.

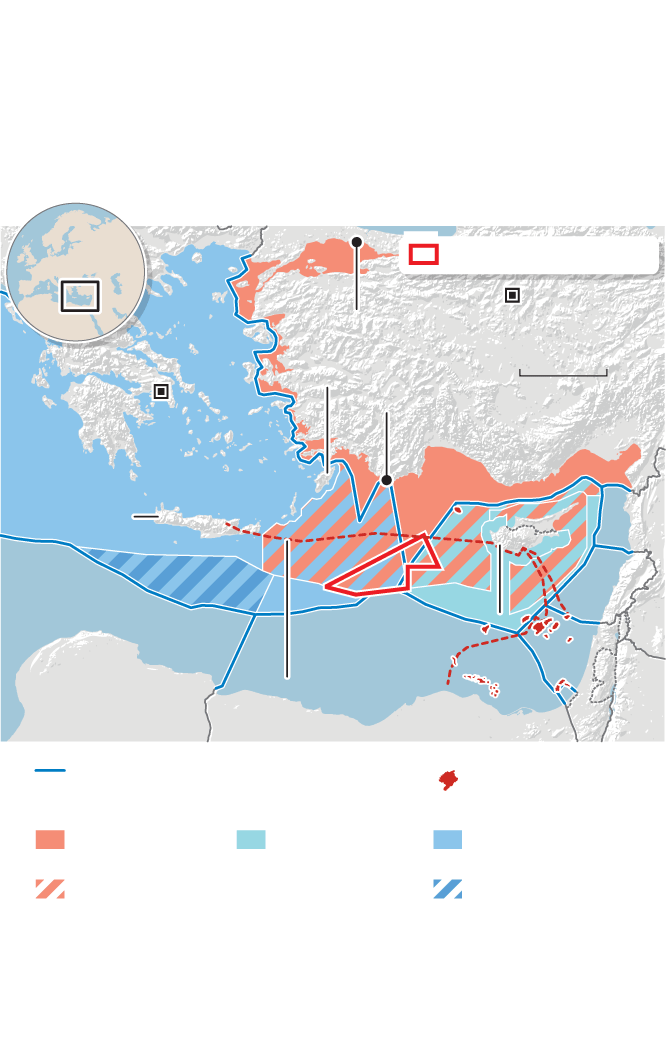

Turkey-Greece tensions

in eastern Mediterranean

Greece’s military has been put on alert after

Turkey announced that it would be conducting

energy exploration in the eastern Mediterranean

in an area Athens says overlaps its continental shelf

Turkish survey area

Detail

Ankara

Istanbul

TURKEY

0

200

Athens

Rhodes

KM

Kastellorizo

(Greece)

GREECE

Aegean

Sea

Crete

SYRIA

LEB.

CYPRUS

Med. Sea

Proposed

gas pipelines

LIBYA

ISRAEL

EGYPT

Exclusive economic

zone (EEZ) boundary

Gas field

Turkey EEZ

Cyprus EEZ

Greece EEZ

Continental shelf claimed

by Turkey

Continental shelf

claimed by Libya

the globe and mail, Sources: graphic news

(via AP, Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Wall Street Journal); FT

Turkey-Greece tensions

in eastern Mediterranean

Greece’s military has been put on alert after Turkey an-

nounced that it would be conducting energy exploration

in the eastern Mediterranean in an area Athens says

overlaps its continental shelf

Turkish survey area

Detail

Ankara

Istanbul

TURKEY

0

200

Athens

Rhodes

KM

Kastellorizo

(Greece)

GREECE

Aegean

Sea

Crete

SYRIA

LEB.

CYPRUS

Med. Sea

Proposed

gas pipelines

LIBYA

ISRAEL

EGYPT

Exclusive economic

zone (EEZ) boundary

Gas field

Turkey EEZ

Cyprus EEZ

Greece EEZ

Continental shelf claimed

by Turkey

Continental shelf

claimed by Libya

the globe and mail, Sources: graphic news (via AP,

Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wall Street

Journal); FT

Turkey-Greece tensions in eastern Mediterranean

Greece’s military has been put on alert after Turkey announced that it

would be conducting energy exploration in the eastern Mediterranean

in an area Athens says overlaps its continental shelf

Turkish survey

ship Oruç Reis

Turkish survey area

Detail

Ankara

Istanbul

TURKEY

0

200

Athens

Rhodes

KM

Kastellorizo

(Greece)

GREECE

Aegean

Sea

Crete

SYRIA

LEB.

CYPRUS

Mediterranean Sea

Proposed

gas pipelines

LIBYA

ISRAEL

EGYPT

Exclusive economic zone (EEZ) boundary

Gas field

Turkey EEZ

Cyprus EEZ

Greece EEZ

Continental shelf claimed by Turkey

Continental shelf claimed by Libya

the globe and mail, Sources: graphic news (via AP, Turkish Ministry

of Foreign Affairs, Wall Street Journal); FT; Picture: AP

Turkey’s current land and maritime borders largely reflect the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which officially settled the conflict between the Ottoman Empire, France, Italy, Greece and Romania. Mr. Erdogan wants the treaty renegotiated. Unless it is, he has made it clear that he will make trouble. That’s already happening.

Last November, Turkey signed a maritime agreement with Tripoli’s Government of National Accord, the UN-backed regime in Western Libya, that establishes an EEZ extending from Libya’s northeast coast to Turkey’s southwestern Mediterranean shore. It cuts like a knife through the waters near Crete that are claimed by Greece.

The Eastern Mediterranean and much of the near Middle East have been energy-poor regions pretty much forever. The oil and gas riches went to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iran and Iraq – all of them members of today’s OPEC, none of them with borders on the Mediterranean itself.

The energy balance began to shift ever so slightly in the Eastern Mediterranean’s favour about a decade ago, when Texas’s Noble Energy found gas reserves in the deep waters off Israel’s coast and developed the enormous Leviathan gas field, which began commercial production late last year.

Soon thereafter, the Republic of Cyprus, the Greek-speaking southern half of the island whose northern half is claimed by Turkey, also found gas. In 2015, Eni, the national Italian energy company that is considered one of the global oil industry’s seven “supermajors,” added to the region’s energy potential in a big way with the discovery of the Zohr gas field off Egypt. Zohr, which started production in 2017, is said to be the biggest gas find ever in the Mediterranean.

Turkey is desperate for its own gas. The country, which is rapidly industrializing and is a member of the EU’s customs union, imports 98 per cent of its gas needs, mostly from Russia and Iran, supplemented by liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Azerbaijan.

The long-term contracts with Russia and Iran expire in a few years, and Turkey is eager to boost its negotiating leverage by finding competing supplies, preferably ones it controls. Recently it has explored the Black Sea and claims to have made an enormous discovery, but the size of the field has not been independently verified and some energy analysts doubt it’s as big as Mr. Erdogan claims. He called the Black Sea find the dawn of a “new era,” one that would make Turkey an energy powerhouse and gas exporter. Still, he is obsessed with the Mediterranean.

“Gas is very important for Turkey,” said George Tzogopoulos, a Greek geopolitical author and senior research fellow at the Centre International de Formation Européenne in Nice. “Erdogan wants to use it to bargain with the EU for better EU privileges.”

In addition to securing gas for Turkey, Mr. Erdogan apparently wants his country to play a key role with Greece, Cyprus and Israel in supplying gas to the EU, whose major supplier is Russia, accounting for some 40 per cent of demand. The EU wants to diversify its supplies, but the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which is near completion and would take gas from Russia through the Baltic Sea to Germany, would actually intensify the EU’s reliance on Russian energy.

Nord Stream is not as popular as it once was. U.S. President Donald Trump has condemned the project, and several senior Republicans, including Senator Ted Cruz, have called for sanctions against the German port that is helping to build the pipeline. The Novichok poisoning in August of Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny has heightened calls outside and inside Germany to kill Nord Stream.

“The openly attempted murder through the Kremlin’s Mafia-like structures should not just worry us but needs to have real consequences,” said Katrin Göring-Eckardt, co-chair of the Green Party in the German parliament. “Nord Stream 2 is no longer something we can jointly pursue with Russia.”

Nord Stream’s death, should it happen, would deliver a boost to the proposed EastMed pipeline, which would take gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Italy via Cyprus, Crete and mainland Greece. EastMed has been approved in principle by Greece, Cyprus and Israel, but there is no indication that construction will start soon. The financing is not lined up, and the technical obstacles are formidable.

Turkey opposes the pipeline because it was not invited into the project – it is not a member of the EastMed Gas Forum, which has been called the OPEC of Eastern Mediterranean gas – and because its route would take it through disputed Cypriot waters, as well as the area off Crete that Turkey and the Tripoli government agreed was theirs. Turkey extracted the deal with Tripoli in exchange for defending the city from General Khalifa Haftar, the Eastern Libyan warlord, supported by France, who has been trying to conquer all of Libya.

Turkey is isolated. Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt and France are united against Turkish attempts to send its exploration ships into Cypriot waters. But Turkey has a formidable navy, one that could inflict a lot of damage on the Greek navy’s aging ships, and Mr. Erdogan could threaten to send hundreds of thousands of the 3.9-million refugees in his country into Greece and beyond unless Turkey gets a seat at the gas table. He also knows that Mr. Trump has little interest in brokering a Turkish-Greek-Cypriot gas agreement with the U.S. election approaching.

Analysts agree that a battle could erupt between Greece and Turkey if Turkey were to send exploration and navy ships to the waters around Crete. So far, Mr. Erdogan has given no hint that he would do so, but he could force a resolution that would give his country exploration and drilling rights in some of the disputed areas.

“You can’t always predict what Erdogan will do,” said Mr. Lindenstrauss of Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies. “And the current environment will not allow a grand diplomatic bargain.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly