Archeologist Wang Shejiang stands outside Dragon’s Tooth Cave, one of many archeological sites in China's Luonan area.Nathan VanderKlippe/The Globe and Mail

This is part of a Globe and Mail series in which Beijing correspondent Nathan VanderKlippe looks at China’s present and future challenges before his return to Canada.

The dark cleft in the cliff is barely big enough to be called a cave. Inside, there is room for a few people at most. But this unassuming spot in a distant corner of China has nonetheless been a haven for humanity and its predecessors for at least a half-million years.

The Dragon’s Tooth Cave looks over the rolling greenery that surrounds the Luo River, a tributary of the Yellow River. As archeologist Wang Shejiang dug through its layers, he discovered traces of grease still clinging to stone tools. It was evidence that campfires have been used here since the distant dawn of prehistory to grill meat.

In the decades since he began studying the cave site in 1995, Mr. Wang has identified hundreds of nearby archeological sites.

Can China make its people happy?

Looking out from the mouth of the cave, his finger darts to point out the hilltops where he discovered traces of prehistorical inhabitation.

At an apartment construction site a short drive away, technicians are excavating stone tools from a small plot, where flags flutter over dozens of ancient tools exposed inside a grid of square holes.

Digs elsewhere suggests the earth will yield new artifacts down as deep as 15 metres below the surface, to a layer 650,000 years old. And a series of finds in the region have pointed to prehuman habitation more than two million years ago.

An artifact from Luonan recorded by Mr. Wang.Courtesy of Wang Shejiang

In this corner of Shaanxi province, on the fringes of the Qinling Mountains, relics are “basically everywhere. Wherever you dig, you can find them,” said Mr. Wang a researcher with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

While offering new details about how people moved across the Earth since the origin of the species, these discoveries are also providing new ways to bolster nationalist sentiment and strengthen Communist Party rule – even if scientific fact occasionally conflicts with government claims.

President Xi Jinping has placed unusual attention on the past as a key to understanding Chinese greatness – an idea that history is destiny – and described archeology in particular as a tool of “great socio-political significance.” Chinese civilization “has unique cultural genes and its own development history, rooted in the land of China,” he wrote last year in an article published under his name in Qiushi, the Communist Party’s top theory journal.

Indeed, archeology has shown, he wrote, that China “is the hometown of eastern humans” and ranks alongside Africa “as the earliest place of human origin.”

At top, workers search for ancient stone tools at a dig site in Luonan. At bottom, Mr. Wang addresses a group of schoolchildren who are being taught about the archeological findings.Photos: Nathan VanderKlippe/The Globe and Mail; courtesy of Wang Shejiang

The value of ancient discoveries is apparent at a museum nearby the Dragon’s Tooth Cave, which displays paleolithic tools next to a sign declaring the facility as a base for patriotic education.

Students from local schools have been brought into the museum “to receive education in patriotism and traditional culture,” state media have reported, in response to calls from Mr. Xi to “let the cultural relics live.”

It’s a campaign that has showered new spending and attention on some of the country’s thousands of museums, part of a broader government effort to seek a better quality of life for people, rather than mere raw economic expansion.

But archeology has also become a tool to assert Chinese sovereignty, including over places such as Tibet. Researchers have pointed to similarities in stone tools found alongside the Yangtze River with those on the Tibetan plateau to indicate shared roots.

More recently, researchers have attracted national attention for establishing a genetic link between modern-day Tibetans and Denisovans, a little-understood distant relative of the Neanderthal that appears to have lived across Asia hundreds of thousands of years ago.

This could indicate a direct lineage between the long extinct Denisovans and the current occupants of the region, according to Chen Fahu, the director of the Institute of Tibet Plateau Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

A virtual reconstruction of the mandible of a Denisovan found in a cave on the Tibetan Plateau in 1980.Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology/JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN/AFP/Getty Images

All of this work has led to a considerable reconsideration of the role played by what is now China in human history. In the 1930s, as archeological discoveries accumulated in Europe, scholars in China “assumed that we must have been foreign to the land and arrived late,” Mr. Chen said. Work in subsequent years has turned that belief on its head. In the Luonan area, the region around the Dragon’s Tooth Cave, for example, “there have been human activities” for more than a million years, he said, in “a continuous process.”

China’s leaders have employed these archeological findings as a means to bring together various ethnic groups into “the ‘trunk’ of the Chinese ethnicity,” said Jeremy Paltiel, an expert on China at Carleton University. Discussion of the Denisovan genetic links, he noted, was carried in the Forum of National Strength, a particularly nationalist imprint of The People’s Daily.

“The implication seems to be that Chinese have a shared genetic history that is at once distinctive from that of modern Europeans,” Prof. Paltiel said.

It is a modern-day echo of a near century-old theory of “sinocentric ethno-nationalism,” which argued that “all the diverse ethnic groups within the territory of China shared a common ancestor back to antiquity,” according to research from Hsiao-pei Yen, a scholar at the Institute of Modern History with Academia Sinica in Taipei.

Prof. Paltiel sees a more modern imperative. Under Mr. Xi, the Chinese Communist Party “has moved from emphasizing China’s exception to the liberal West to active celebration of China’s unique and distinctive contribution to humanity and the making of modernity,” he said.

“Exceptionalism carries the nagging possibility of inferiority or worse; a dead end,” he said. But in lauding historical distinctiveness, “China and its governance system become an equally legitimate variety of mainstream modernity, equal to and in no way inferior or less valid than the liberal West.”

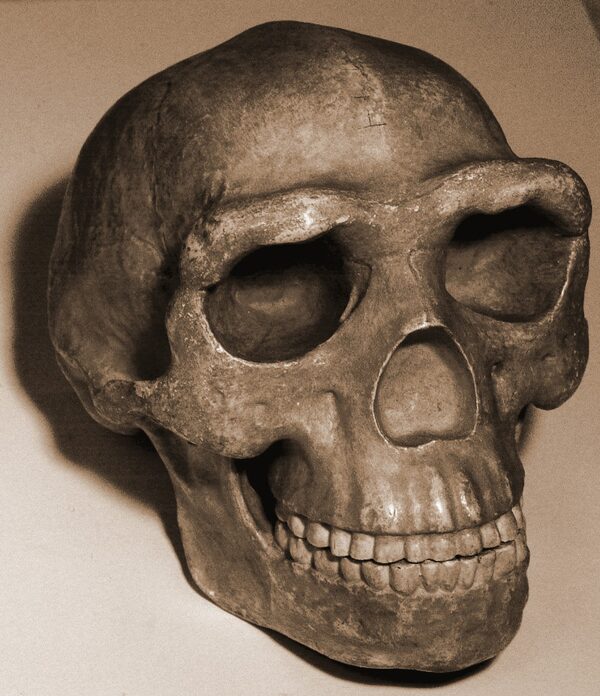

Peking Man, shown in a skull reconstruction, was a 500,000-year-old hominid fossil found in the 1930s near Beijing, then known to westerners as Peking.kevinzim/Wikipedia Commons

Indeed, China under Mr. Xi has sought to curry a greater sense of what he has called “cultural self-confidence,” through tracing Chinese roots to the very earliest indications of prehuman habitation. In the Qiushi article, Mr. Xi praised the “invention” of fire techniques by Peking Man 500,000 years ago and paid homage to the archeological confirmation of millions of years of human history on soil that is now part of China. These constitute the “historical context of the origin and development of Chinese civilization,” he said.

That, too, is a revival of an old idea. The Peking Man fossils discovered in the 1930s (by a team led by a Canadian, Davidson Black) were at the time oldest human record discovered, sparking a national fervour subsequently seized by Mao Zedong’s Communist leadership. Peking Man was in the 1950s “drenched in national symbolism,” seen by some as “a Chinese ancestor, if not an ancestor of all people,” Sigrid Schmalzer writes in The People’s Peking Man.

That thinking has never vanished. Ms. Schmalzer cites a 2002 letter from an amateur Chinese fossil collector: “Indians, Soviets, Native Americans and British people are all the descendants of Chinese people,” the man wrote her. “We humans will in the end realize communism – international communism.”

Prof. Wang expresses understanding of the modern political appeal of archeological discoveries. Finding relics of ancient inhabitation can, for those who live there today, provide a kind of comfort. He likens it to placing ancestral heirlooms on a living room shelf.

It can make a person feel that their “family’s cultural heritage is very deep,” he said. But “if there is nothing, it is empty.”

He nonetheless sees no archeological evidence for a distinct Chinese lineage.

“If you go back to the beginning, we are all the same,” he says. “Everyone was in Africa at the earliest time. Any so-called difference is only in the origin of modern people. Modern people arrived in other places from Africa.”

The importance of Peking Man, too, has been eclipsed by the far more complete fossil record assembled in Africa and Europe. Evidence for first use of fire has been found among humans who lived hundreds of thousands of years earlier at sites in modern-day France and Israel.

China is not unique in using archeology to stir national sentiment, said Bence Viola, an archeologist at the University of Toronto who is a leading Denisovan scholar. Many of its neighbours, particularly in Central Asia, have done the same. But he finds it especially puzzling for China, given the legitimate claims the country can make.

“I always think they should feel very, very proud of having a 7,000- or 8,000-year-old civilization – which I think is in many ways the oldest in the world. You don’t have to make up that it goes back 300,000 years, because it’s not true,” he said.

“But there are always political considerations.”

More: A parting view from Beijing

Nathan VanderKlippe has been The Globe’s Beijing-based correspondent since 2013 and has seen the ambitions and discontents of Xi Jinping’s China take shape. He outlines some key areas to watch around China’s political and economic ambitions as it also represses ethnic minorities and holds two Canadians captive.

The Globe and Mail

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe