Michael Hurst at the Kinkaseki copper mine camp Memorial.

Growing up in Oshawa, Ont., after the Second World War, Michael Hurst was familiar with the stories of Canadians – including his uncles – who had served in Canada’s forces both at home and overseas in the European theatre.

And even as a boy, he knew he wanted to do something to say thank you to those who had fought. Four decades later he got his chance – in Taiwan, a place he’d never associated with the conflict but where, he soon discovered, thousands of Allied soldiers were held as prisoners of war from 1942 to 1945.

While many North Americans can recite the names of famous battles and operations in Europe – such as D-Day, Dunkirk and the Battle of the Bulge – few have such knowledge of the fighting that took place in the Asia-Pacific region. Even less is known about the POW camps of Taiwan and the men subjected to the brutal conditions within. It is Mr. Hurst’s mission to tell their stories.

In 1996, Mr. Hurst, who had moved to Taiwan for business, heard about the Kinkaseki copper mine in Jinguashi, near Taipei, where captured Allied soldiers sent to Asia to defend against Japan’s invasion were held. They were forced into slave labour, working in copper mines, removing stones from a massive valley to plant sugar cane, digging a flood-diversion channel in a river or creating a man-made lake.

The story captured his attention, especially the courage and kindness of a Canadian doctor, Major Ben Wheeler, who saved many of his fellow prisoners’ lives.

“They were basically forgotten for more than 50 years,” said Mr. Hurst, now 73. “I thought the men here should be remembered.”

So he got to work.

Over the past 24 years, he has identified all of the 4,370 former prisoners who were held in Taiwan’s 16 POW camps, and contacted more than 800 of them or their families. He founded the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society, and his book Never Forgotten was published earlier this year. It’s a compilation of the POWs’ experiences, as recounted to Mr. Hurst, as well as their diaries, drawings and other never-before-published wartime material.

“The prisoners told me, ‘We’re so glad that finally in our lives, somebody cared,’” Mr. Hurst said.

The POW camps in Asia were notoriously brutal. Atrocities committed along the so-called Death Railway, in Thailand and Myanmar, inspired The Bridge on the River Kwai. The Empire of Japan had signed the 1929 Geneva Convention, which decreed that prisoners of war must be treated humanely, but never ratified it. Conditions in Taiwan, Mr. Hurst said, were “some of the worst in Asia.”

Senior British, American, Australian and Dutch officers were kept on the island because it was considered safer; Taiwan was then a colony firmly under Japan’s control.

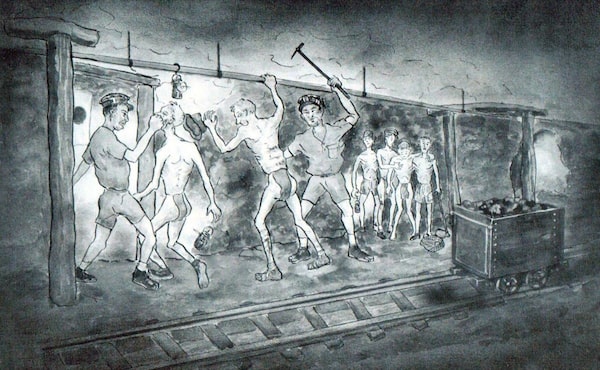

POWs were subjected to physical abuse and horrible living conditions. The most atrocious camp was the Kinkaseki mine. The men worked in holes that reached temperatures of more than 40 degrees in the summer; in the winter it was so cold that many prisoners died from exposure. If they didn’t meet their daily quota, guards would beat them with mining hammers.

Drawing of men being beaten with hammers by the camp guards for not meeting their quota at the Kinkaseki mine. CREDIT TO Taiwan POW Camps Memorial SocietyHandout

“I ... heard the dull thwack of the hammer shaft on the backs of those in line before me,” Mr. Hurst quotes Harry Blackham in his book, as the prisoner describes one of the first beatings he received at Kinkaseki, when he was 22. “Apprehensive and scared, I could only take a deep breath and grit my teeth until it came: a searing, ripping pain across my kidneys, followed by several more across my back. The pain was incredible, intensifying what was almost unendurable agony. … This was to become an almost daily occurrence.”

The prisoners were given a meagre diet of mainly rice with thin vegetable soup; in most cases their body weight fell to just 50 per cent of what it was before, according to Mr. Hurst’s research. They were forced to work even when they were sick, and those dying were denied treatment. Dr. Wheeler, who was from Edgerton, Alta., and in the British Indian Army, “performed miracles as the Japanese gave him very little medicine to work with,” Mr. Hurst said.

In one of Dr. Wheeler’s diary entries he wrote: “Time passes somehow, the days very quickly but the weeks like months and the months like years. It is hard not to become discouraged. My job is so hopeless without medicine. Cases of beriberi and other avitamine diseases are increasing. … Every day one, two, three or more faint from sheer weakness. … We just cannot exist this way for long. God, when will the end of all this be in sight. What will it be like when the end comes? Still, we can only live from day to day and never lose hope or heart.”

Despite practically no access to drugs or equipment, Dr. Wheeler managed to carry out life-saving procedures. He performed surgeries such as appendectomies using just a pair of dental forceps and a razor blade, and no anesthetic. When one prisoner was brought into the camp’s makeshift hospital paralyzed from the waist down after a rockfall, camp handymen, acting on Dr. Wheeler’s instructions, built him a wooden cradle; other patients spent hours, day after day, massaging his legs to keep the muscles alive. He was eventually able to walk again, after pedalling every day on an exercise bike the physician made for him.

The men became closer than family; supporting each other helped them survive, Mr. Hurst learned. The guards would halve the meal rations of men too sick to work, but the prisoners would pool all the food together and divide it up again so those who were ill would get their full share.

As it became clear Japan was losing the war, an order came from above to build a tunnel from the Kinkaseki camp to the mine, under the pretense of making it easier for the prisoners to get to work. The real purpose was to use the tunnel to exterminate them and leave no trace if the Americans invaded, Mr. Hurst said, citing a document retrieved from the camp.

Fortunately, that plan was never executed. On August 15, 1945, Imperial Japan surrendered.

When the POWs realized the Allies had won the war, they were overjoyed their nightmare was over. Upon returning home, however, the men often received little help, and were ordered by their governments not to speak publicly about their imprisonment in order to avoid accusations that wartime strategies may have led to so many of the soldiers being captured, Mr. Hurst learned. When the men tried telling their families, the response was often disbelief, so they simply stopped bringing it up.

Many of the men also wanted to put the ordeal behind them.

Anne Wheeler, Dr. Wheeler’s youngest child, recalled she never heard her father talk about his experience in Taiwan, or speak badly of the Japanese.

“My father thought if he was going to have any kind of a normal life, he would have to put that behind him. … He and my mother had been separated for five years because of the war. … He wanted to cherish every moment of his life,” said Ms. Wheeler, a filmmaker who made a docudrama about her father, A War Story, in 1981.

Men who could not cope with the trauma ended up in mental institutions, divorced or taking their own life, Mr. Hurst said. Because of illnesses related to their camp experience, some of the former prisoners died prematurely, as Dr. Wheeler did at the age of 53.

But many had the strength to go back to normal lives, working in garages or delivering mail, getting on with raising their families, while quietly keeping the treatment they endured to themselves.

“There would never be a match for these people,” said Mr. Hurst, calling them “heroes of our lifetime.”

The POWs wanted an apology and compensation from Japan, but they eventually gave up on getting these – or even an acknowledgement of the atrocities committed against them, Mr. Hurst said.

“The guys in Normandy and Iwo Jima, they’re going to be known, they’re heroes. But the guys who spent three years in a Japanese prison, they were going to be forgotten.”

In 1997, Mr. Hurst worked with Canada’s Trade Office in Taipei and the Canadian Society in Taiwan to hold a commemorative service for the former POWs. This resulted in a memorial being built on the site of the former Kinkaseki prison camp.

He didn’t stop there.

Mr. Hurst invited a few of the POWs to attend the memorial dedication ceremony, and after seeing how moved they were, became determined to find the other prisoners and identify all the camps in Taiwan.

It was not an easy task. Many records were destroyed when Japan realized it would lose the war, and some of the camps had been built over or turned into barren fields, all signs of their past erased.

Still, slowly, he was able to track down names, one discovery often leading to others. It helped that Mr. Hurst’s company made insignia items. He decided to send medals to the POWs he knew of, and “once they got the medal in the mail, they were over the moon. Then word spread like wildfire.”

Over the years, Mr. Hurst and the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society have built memorial plaques at most of the camps and held many commemorations for the former prisoners, inviting them to attend and find closure in their final years. “They would walk into the former camps with their son and daughter and sometimes they would walk off on their own and have a little cry and remember the men who had died,” he said.

Most of the former Taiwan POWs have now passed away.

As for Mr. Hurst, he has garnered numerous recognitions for his research, including being awarded the Order of the British Empire by the Queen, and received praise for his book.

“It will always be a tremendous resource,” Ms. Wheeler said. “It will always be there as evidence. There is no other book like it, and these stories would have been lost if it were not for Michael’s tenacity. I’m very grateful to him.”

Mr. Hurst’s biggest satisfaction, however, comes from keeping his pledge to honour the veterans.

“The prisoners have always been saying ‘We’re so glad that finally some time in our lives somebody showed us they cared,’” he said. “For someone who went through the trauma, and they couldn’t tell it themselves, that was the most gratifying thing – that somebody was telling their story.”