A page from a B.C. curriculum textbook at a Chinese international school. In China in particular, international education comes with a caveat: Canadian schools have long edited their own instruction, especially in senior high-school social studies classes, to fit the dictates of Beijing rather than the provincial education ministries that approve their textbooks.handout/handout

They have torn pages out of textbooks and placed stickers over content that might offend Chinese officials. They have purged maps that did not show Taiwan as a province of China and urged their staff to show deference to the Communist Party. They have refused to hire teachers who wear hijabs or have links to Tibetan groups.

More than 80 international schools in China teach curricula developed by Canadian provinces and issue provincial diplomas, part of an education business that has become an important pillar of commerce between the two countries. But people who have worked at these schools say they have made compromises to please Chinese authorities and parents whose values may differ from those expected in Canada.

That includes editing their own lesson plans, especially in senior high-school social studies classes, to fit the dictates of Beijing rather than the provincial education ministries that approve their textbooks. Some schools self-censor to avoid problems when they are inspected by local authorities, but in at least one case, the work of tearing out textbook pages was done by Chinese government officials themselves, The Globe and Mail learned in interviews with teachers and principals who have worked in seven Canadian schools in China.

“The main goal is to be respectful to the vision of the Chinese Communist Party,” said Michael Frazer, a former elementary school teacher at the Canadian International School of Beijing. It’s about “making sure that we don’t raise questions against them.”

As one example, classroom discussion of human rights was permitted, he said, but not in a Chinese context. “So we wouldn’t want to bring up the Hong Kong protests for human rights. But we could bring up the United States protests for human rights.”

Canadian provinces generally mandate a standard of education for international schools that parallels what is offered in Canada. Alberta, for example, requires that “accredited international schools must follow the Alberta programs of study.”

In return, the provinces grant diplomas to overseas students, some of whom then enroll in those provinces or elsewhere in Canada. It is a system that for a quarter-century has brought tens of thousands of students from other countries, and China in particular, to Canadian postsecondary schools.

CSIS warns China’s Operation Fox Hunt is targeting Canada’s Chinese community

But Chinese authorities have shown growing interest in international education at a time when demands for ideological conformity are rising across China.

Earlier this year, the government introduced a draft law that proposes new requirements for teachers in China, including 20 hours of political and legal education. It would also explicitly bar “words and actions that damage China’s national sovereignty, security, honour, and the public interests of society,” engaging in religious education, obstructing the country’s education policy and “other actions that seriously violate China’s public order and morals” or professional codes of conduct. The proposed law drew criticism from foreign embassies and business groups in China, and a final version has not yet been enacted.

Schools in China have already made concessions to authorities. At many institutions, new teachers receive instruction about which topics to avoid in class, often reduced to the three Ts – Tiananmen, Tibet and Taiwan – although the list has grown longer in recent years. They are also told to maintain deference to China’s leaders.

It was not uncommon for students to ask about the three Ts, said George Watson, who worked at a series of schools in China, including as a principal, and now runs an education consultancy. “Our instruction was: ‘You look it up on the internet. We’re not talking about it here.’”

Chinese sensitivities have also governed who can be hired. Two former principals recalled being told by Chinese superiors that they could not hire certain qualified candidates. One was told to reject a Canadian teacher whose résumé listed experience supporting a Tibetan organization. Another was told by the school’s owner to turn down two applicants, both certified Canadian teachers, “because they wore a hijab.” The owner thought parents would complain that they “didn’t look Canadian enough.”

The Globe is not identifying the principals because they fear professional and personal reprisals.

The Globe’s findings are “concerning, and we would like to look into more info,” said Colin Aitchison, the press secretary to Alberta Education Minister Adriana LaGrange.

In British Columbia, the government ensures teachers and administrators at overseas schools hold B.C. credentials, but “the ministry is not party to the employment relationship between teachers and employers,” said Craig Sorochan, a spokesman for the Ministry of Education.

Provincial “oversight focuses on ensuring that the B.C. curriculum is being implemented at all B.C. offshore schools and that schools are meeting set learning standards,” Mr. Sorochan said. He would not comment on whether tearing pages from textbooks would constitute a violation of those standards.

“Ultimately, schools must operate within local requirements and guidelines,” he said.

Overseas schools themselves offer relatively modest revenue for provinces. B.C., for example, charges $15,000 a year in curriculum and administration fees, plus $350 a student (there are currently more than 12,000 at B.C. offshore schools) and the cost of travel for annual inspections.

Far more money lies in equipping students with credentials to attend university in Canada. Institutions such as the Canadian International School of Beijing send roughly half their graduates to Canadian universities. At the University of British Columbia, international student tuition now exceeds $50,000 a year in some programs.

None of the people interviewed by The Globe questioned the academic standard of education at Canadian schools in China.

“I have no concerns about the legitimacy of their diplomas or that they have learned as much as a student in Canada,” said Alana Prud’homme, who worked as a teacher and administrator at an international school in Henan province.

But Ms. Prud’homme, who is now back in Canada, worries that other expectations of a Canadian education weren’t always met. “We want our students to be worldwide citizens. We want them to be critical thinkers,” she said.

“And that’s the stuff where I feel more concerned about that, well, we’re not allowing them to actually see information from all sides.” In China, “we don’t have the freedom to do that.”

One former principal in China described removing pages from a brand-new Alberta social studies textbook. Among the deleted pages was a section on Tibet and the Pursuit of National Self-Determination, which describes the Tibet Autonomous Region as “a province of China” that was “once part of a separate nation.” The textbook includes a photo of the Dalai Lama and appends a 1950 quote in which he says, “The armed invasion of Tibet for the incorporation of Tibet in Communist China through sheer physical force is a clear case of aggression.”

China has deemed its invasion of Tibet a “liberation,” saying many Tibetans were treated like slaves before the region came under Communist control.

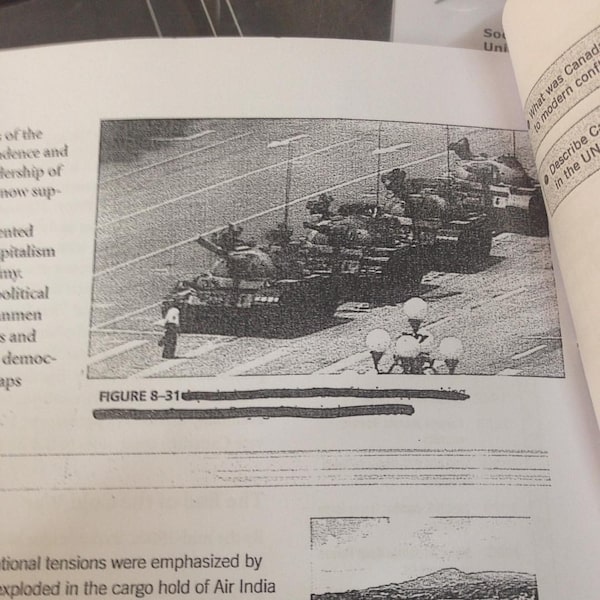

The principal also described placing white stickers over part of a textbook page that included the famous photograph of “Tank Man,” who stepped in front of tanks rolling near Tiananmen Square during the protests in 1989. The textbook describes him as “courageous.”

The Globe is not identifying the principal because they fear professional reprisals for describing the redaction.

The Alberta textbook encourages students to consider the Tiananmen Square massacre “from a variety of points of views and perspectives,” including those of the Chinese government, and audiences inside and outside China.

In China, however, that page in the textbook was blocked, and government largely censors the “Tank Man” image.

B.C. high-school history books received similar treatment. Tiananmen Square is something “you don’t talk about in China,” Mr. Watson said. “So the textbooks had to be changed. We basically ripped those sections out and don’t talk about them.”

Some educators see value in such actions. It is helpful to teachers in China to steer them away from topics likely to create anger or provoke government reprisals, Mr. Frazer said. Better that than “just blindly going out there and causing an unneeded and unwarranted fuss over something where the concept could have been easily taught through a different lens and be just as powerful.”

Mr. Watson acknowledged the seriousness of eliding certain topics, likening it to removing “stuff about residential schools” from a textbook in Canada. “That, in Canada, I would have probably found personally offensive.”

But teaching at international schools means signing up for a different mission, he said.

“Our job and the reason that we were in China was to provide a pathway to graduation, so that the Chinese kids could get into Western universities,” he said. “So the development of English-language skills was more important than whether we talked about Tibet or Taiwan.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe