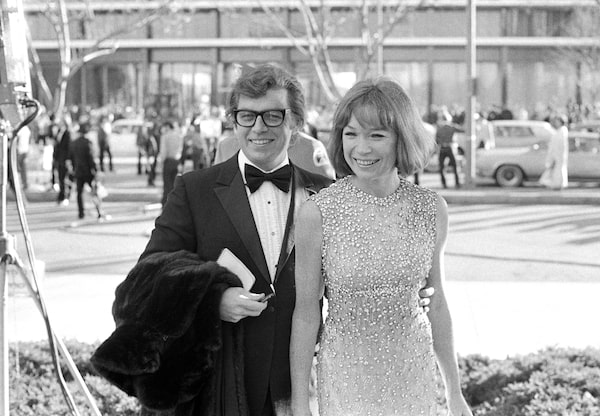

Columnist Pete Hamill and actress Shirley MacLaine arrive for the Academy Awards, April 2, 1974 in Hollywood.Bettmann / Getty Images

Pete Hamill, a high-school dropout who turned a gift for storytelling, a fascination with characters and a romance with tabloid newspapers into a storied career as a New York journalist, novelist and essayist for more than a half century, died on Wednesday in Brooklyn. He was 85.

The writer Denis Hamill, his brother, said he had fall at his home in Manhattan on Saturday after returning from receiving dialysis and was in intensive care at Methodist Hospital when “his kidneys and heart failed him.”

In another age, when the newsrooms of metropolitan dailies pulsed to the rising thunder of typewriters on deadline, Mr. Hamill, searching for a future after years of academic frustration, Navy life and graphic design work, walked into the city room of the New York Post in 1960 and fell in love with newspapering.

“The room was more exciting to me than any movie,” he recalled in memoirs, “an organized chaos of editors shouting from desks, copy boys dashing through doors into the composing room, men and women typing at big manual typewriters, telephones ringing, the wire service tickers clattering, everyone smoking and putting butts out on the floor.”

Mr. Hamill became a celebrated reporter, columnist and the top editor of the New York Post and the Daily News; a foreign correspondent for The Post and The Saturday Evening Post; and a writer for New York Newsday, The Village Voice, Esquire and other publications. He wrote a score of books, mostly novels but also biographies, collections of short stories and essays, and screenplays, some adapted from his books.

Breslin and Hamill: HBO’s great documentary celebration of old-school journalism

He was a quintessential New Yorker – streetwise, empathetic with the city’s masses and enthralled with its diversity – and wrote about its major events in a literature of journalism. Along with Jimmy Breslin, he popularized a spare, blunt style in columns of on-the-scene reporting in the authentic voice of the working classes: blustery, sardonic, often angry. When riots erupted in Brooklyn in 1971, he wrote in The Post:

“If people say nothing can be done about Brownsville, they lie. If this country would stop its irrational nonsense and get to work, every Brownsville would be gone in five years. Get the hell out of Asia. Stop feeding dictators. Forget about airports, SSTs, Albany Malls, highways. This country can do anything. And if Brownsville stays the way it is for another year, someone sleek and fat and comfortable should go to jail.”

He idolized Hemingway and covered wars in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Lebanon and Northern Ireland. He lived in Dublin, Barcelona, Mexico City, Saigon, San Juan, Rome and Tokyo. But his roots were in New York, where he pounded out stories about murders, strikes, the World Series, championship fights, jazz or politics, and then got drunk after work with buddies at the Lion’s Head in Greenwich Village.

His presence at crises was uncanny. In 1968, he was steps away from his friend Senator Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles on the night he was assassinated and helped subdue the killer, Sirhan Sirhan. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was blocks away when terrorists attacked the World Trade Center, killing thousands, and described it in The Daily News.

Unlike most print journalists, Mr. Hamill was a bona fide New York celebrity, featured in gossip columns squiring Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Shirley MacLaine or Linda Ronstadt; promoting his books on television; photographed at society charity events or imbibing with the glitterati at parties. His friends included Norman Mailer, Jules Feiffer and Jack Lemmon.

In a tuxedo at a gallery opening or in shirt sleeves at the city desk, he looked like a fighter: a muscular, grizzled, chain-smoking raconteur who told stories in a whisky baritone of growing up in a big Irish family in Brooklyn, of newsmen he had known, stories he had covered and characters he had met around the world – grist for the novels he churned out, sometimes holing up for weeks and working around the clock.

He was widely respected in newspaper circles, not only for his innovative writing and advocacy of underdogs, but for promoting higher tabloid news standards and for standing up to publishers in squabbles over pay and treatment of employees and his own autonomy as an editor.

His first crack at running a newsroom came in 1993, when Peter Kalikow, who had bought The Post from Rupert Murdoch in 1988, went bankrupt. Steven Hoffenberg, a shady financier who later went to jail, secured control and asked Mr. Hamill to become editor-in-chief and rescue the shaky paper. He was enthusiastic about it, had fresh ideas and seemed a perfect choice to resuscitate the patient. He would also write a column.

But he had three conditions: restoration of a 20-per-cent pay cut recently imposed on the staff, money to hire more reporters and absolute editorial autonomy. Mr. Hoffenberg agreed. A month later, however, Abraham Hirschfeld, a buffoonish parking-lot mogul who knew nothing about newspapers, won a court case to buy The Post.

He fired Mr. Hamill. The staff mutinied, publishing an entire edition filled with scathing pieces about the new owner. Mr. Hamill was rehired with a big, wet Hirschfeld kiss. Later, in his own protest over staff dismissals, he briefly edited the paper from a nearby diner. New Yorkers relished the uproar, but the turmoil ended when Mr. Murdoch bought The Post back and terminated Mr. Hamill.

In 1997, he got another chance, this time at The Daily News. Mortimer Zuckerman, the owner, hired him to replace a British editor who had turned it from a brash, tough-guy paper into a tattler of celebrity gossip and supermarket tabloid stunts to compete with The Post and New York Newsday.

Mr. Hamill refocused on city news, covering immigrants, ethnic communities, Russian mobsters and infrastructure problems. He serialized Mr. Mailer’s novel The Gospel According to the Son. Circulation fell, and Mr. Hamill clashed with Mr. Zuckerman, but staffers said he brought glamour, collegiality and respectability to the paper. More than 100 of them signed a letter urging Mr. Zuckerman to retain him. “He’s a mensch,” said JoAnne Wasserman, a reporter. But after eight months, he resigned under pressure.

Mr. Hamill became nationally known for articles in Vanity Fair, Esquire, The New Yorker and other magazines, and for books. His first novel, A Killing for Christ (1968), spun a plot to assassinate the pope. “Pete Hamill is set on ripping the lid off the rotten church, the rotten upper classes, the rotten rightists,” John Casey wrote in a not entirely favorable review in The New York Times.

Most of his fiction was set in New York, including The Gift (1973) and Snow in August (1997), both of which drew on his youth; Forever (2003), the story of a man granted immortality as long as he never leaves the island of Manhattan; North River (2007), a Depression-era tale of a man and his grandson; and Tabloid City (2011), a stop-the-presses murder yarn.

More than 100 Hamill short stories ran in a Post series called The Eight Million and in a Daily News series, Tales of New York. His story collections, The Invisible City: A New York Sketchbook (1980), and Tokyo Sketches (1992), were hailed by Publishers Weekly: “His simple themes of love, loss, longing and deception are joined to powerful emotions and reveal a psychological bond” between America and Japan.

William Peter Hamill Jr. was born in Brooklyn on June 24, 1935, the eldest of seven children of Billy and Anne (Devlin) Hamill, immigrants from Belfast. His mother was a cashier at a movie theater and a midwife in the maternity ward of Methodist Hospital, and his father, who lost a leg in a soccer accident, was often unemployed but sometimes worked in a factory.

Pete went to a Roman Catholic school and delivered The Brooklyn Eagle. Fascinated with comic books, he began drawing. He attended Regis High School in Manhattan, but dropped out in his second year to work at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In 1952, he joined the Navy. Discharged in 1956, he studied at the Pratt Institute in New York and at Mexico City College.

Back in New York in 1957, he became a graphic designer for three years, but his future remained cloudy. Then a letter to James Wechsler, editor of the New York Post, got him a tryout as a reporter, even though he had no daily journalistic experience. He was hired, got drunk in celebration and was soon writing prizewinning articles.

In 1962, he married Ramona Negron. They had two daughters, Adrienne and Deirdre, and were divorced in 1970. In 1987, he married Fukiko Aoki, a Japanese journalist; he leaves her. In addition to his brother Denis, a journalist, novelist and screenwriter, he also leaves three other siblings – Kathleen, a human-rights lawyer; Brian, a photographer; and John, a spokesman for the Federal Emergency Management Agency – as well as his two daughters and a grandson.

He began writing magazine articles during a 114-day New York newspaper strike in 1962-63. He moved to Spain, covering conflicts in Ireland and Lebanon for The Saturday Evening Post, but he rejoined the New York Post in 1965 and was its correspondent in Vietnam in 1966. Over the next four decades, he wrote books and produced thousands of columns for The Post, The Daily News and New York Newsday. He also wrote for films and television shows and occasionally appeared onscreen, usually – as in The Paper (1994) and The Insider (1999) – as himself or a character very much like him. He was prominently featured in Ric Burns’s multipart 1999 TV documentary, New York, and he and Jimmy Breslin were the subjects of a 2018 documentary, Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists.

His non-fiction included Irrational Ravings (1971), Piecework (1996), Why Sinatra Matters (1998), Diego Rivera (1999) and Downtown, My Manhattan (2004). His memoirs, A Drinking Life (1994), chronicled decades of alcoholism, ending on New Year’s Eve 1972, when he took his last, a vodka and tonic.

In 1976, Mr. Hamill won a Grammy Award for his notes on Bob Dylan’s album Blood on the Tracks. In 2014, he won a George Polk Career Award for his lifetime contributions to journalism.

In recent years he had lived in Tribeca, in lower Manhattan, was a writer-in-residence at New York University, and loved aimless walks. “You can just sit on a bench and look at the harbor, or look at the people,” he told the Times in 2013. “Like being a flâneur. You can just wander around and let the city dictate the script.”