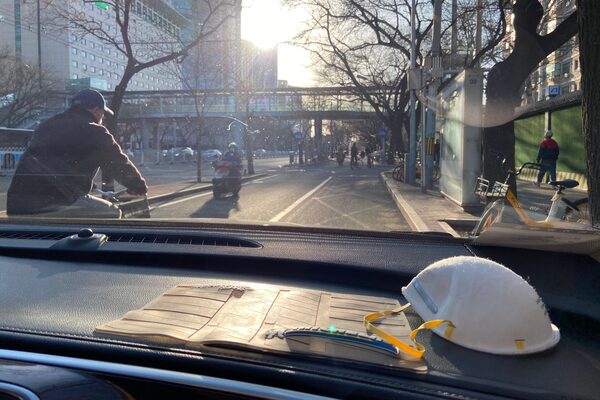

A face mask lies on the dashboard as The Globe and Mail's Asia correspondent Nathan Vanderklippe reports from Beijing.Nathan VanderKlippe/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

Beijing

A man in head-to-toe protective gear emerged like a space creature from the bus that pulled up to my apartment complex in Beijing this week. Moments later, my wife and two sons followed, lugging heavy bags. They haven’t been home since Jan. 22, when we left on a family vacation in Laos. Rather than return to a shuttered city as the novel coronavirus spread across China, they then flew to Canada.

Now, after nearly seven weeks of struggling through e-classes and imposing on family hospitality, they’re back.

It wasn’t much of a reunion. My boys didn’t dent my ribs with a high-speed run-and-hug. My wife didn’t duck a kiss the way she always does after a long time apart. Instead, I sat inside a parked car and watched from a distance as they arrived and walked into a 14-day quarantine, a requirement for each person landing from overseas.

As a bus brought his wife and children to his apartment, Mr. VanderKlippe had to leave to avoid breaking their two-week self-isolation.Nathan VanderKlippe/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

Most people are sent to hotels designated as isolation facilities. We are lucky: Local authorities have allowed the elderly and those with young children to quarantine at home.

But such dispensation is available only to those with empty houses. That means I had to move out, with a pledge not to return for two weeks. My family, however, avoided two weeks locked in a cramped hotel room after what was already a uniquely stressful journey. They transited through Taiwan, which closed its borders to foreigners while they were airborne. The Taipei airport was filled with the wheelchair-bound elderly, desperate to return home from the ravages of a spreading disease.

As for me, I hope to stay at a friend’s place. But nothing is certain. Apartment complexes in Beijing currently bar visitors. Just in case, I’ve stored clothes at the office, where there’s a small couch and space to wait out the days until I can get a proper hug. I might even land a proper kiss.

In Wuhan, new coronavirus cases dry up, and a locked-down city has thoughts of freedom

The slow spread of coronavirus in Thailand offers hope warmer weather might bring some relief

San Jose, Calif.

The view from the window of Globe and Mail correspondent Tamsin McMahon in California.Tamsin McMahon/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

The San Francisco Bay Area doesn’t quite have the legendary gridlock of Los Angeles. But it can still take three hours to drive the 80 kilometres from San Francisco to San Jose. So I was shocked last week when the GPS said the trip would take 45 minutes at rush hour.

Travelling the empty highways was the first time I realized that Silicon Valley is an actual valley – a wide open space surrounded by rolling green hills.

It felt like the quintessential California road trip with the streets devoid of the usual throngs of Teslas, buses shuttling workers to tech campuses and goofy little self-driving test cars.

California has an economy larger than most countries. So the order this week to shelter in place – starting in the Bay Area on Tuesday and extended statewide Friday – has been head-spinning. On my morning walk the day the lockdown began, I saw my neighbour conducting a home-schooled gym class. “It says you have to jump 30 times,” she told her son while reading off an iPad. Then I came across my landlord, weeping in her Porsche over whether her tenants would be able to afford their rents.

Americans love their freedom though, so a shocking variety of businesses remained open this week. The line at the Trader Joe’s supermarket snaked around the building in the rain. Liquor stores, garden nurseries and cannabis dispensaries were all open. You could still buy a Captain America-themed smartphone at Target, though not toilet paper. Even in liberal San Jose, crowds rushed the gun stores, which argued the Second Amendment qualifies them as “essential services.”

But in a place where wealth has come so easily for so long there is a growing sense of fear. “We were already hunkering down, not spending a lot of money,” Hal Moore, a neighbour recently laid off as an investment adviser, told me. “Now what are we going to do? Move away?”

Canadians in U.S. scramble to prepare for travel restrictions

‘We’re in a dead end’: Northern California adjusts to coronavirus lockdown

London

The view from Mark MacKinnon's home office in London.Mark MacKinnon/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

Every now and again, when things are particularly bad in the Gaza Strip, due to war or other hardships, I send my old friend Hasan a message to ask how he and his family and friends are coping. In a jarring reversal of roles, this week it was Hasan’s turn to check in on me: “I hope that you and your family are okay,” he wrote to me via Facebook Messenger.

The reason, of course, was the novel coronavirus, which has turned our entire world upside down. In Britain, where I live and which until this week was trying to keep things as normal as possible, the schools were to be finally shut at the end of the day on Friday.

Businesses are now in full-blown panic. The woman who works at the dry cleaner in my neighbourhood, just south of the River Thames in London, thanked me profusely for coming in to pick up some items I’d left there a few days earlier. “Thank you! Some money!” she said, exhaling sharply. She figured she’d be forced to close her shop by Monday.

The man who runs the newspaper shop across the street from the dry cleaner was just as grateful to see me buying an armload of newspapers and magazines. Many of his regular customers, he said, had cancelled their home deliveries – leaving London for family homes in the countryside.

There were still people on London’s streets this week, but most of them were hurrying to shop – or have a last drink in the pub – before the capital is shut down like so many other European cities already have been.

All live entertainment has been cancelled for the foreseeable future, but there was Glastonbury Festival-like crowding at the discount grocery store near my home. Nobody, as Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in a midweek press conference, knows how long this will last.

Gaza is used to living with such uncertainty after 14 years of rule by the Islamist Hamas movement and a blockade imposed by the Israeli military. Many of Gaza’s two million residents haven’t left at the narrowest, a six-kilometre wide strip of land in all that time. Few outsiders enter. But for once, that isolation has its benefits. The Gaza Strip, for now, is one of the few places in the world with zero recorded cases of the coronavirus. Hasan and his family are fine. It’s the rest of us that he’s worried about.

Relative calm breaks out amid the war on COVID-19 in the Middle East

Some Canadian travellers may be stranded for weeks as borders close, Champagne says

From Elizabeth Renzetti's Berlin home office, she has a view of the Volkspark am Weinberg public park.Elizabeth Renzetti/The Globe and Mail

Berlin

When Berghain closed, people knew things were getting serious. On March 11, Berlin’s most famous club, known for its superstar DJs, sex rooms and no-phone policy, announced it was going dark – well, darker – until at least April 20. It made sense, considering that a club called Trompete was one of the early hotbeds for the spread of coronavirus.

Berlin calls itself “the city of freedom,” and the evidence used to be on every corner, in every street. Day drinkers, some in suits, typically lounge outside our local Spati (think of a 7-Eleven, with more beer and cigarettes). The parks are normally full of people staring at the sky, the patios full of friends defying the weather. That’s all gone.

We used to be encouraged to pay with cash. That too is disappearing. “Nur Bar” – cash only – was a familiar sign in bars and clubs, a charming sign of Berlin’s resistance to the tyranny of progress. Now a trendy café in the Pankow borough only accepts cards, which a barista disinfects, standing back to spray from a safe distance. It’s hardly alone. Our grocery store has hastily taped signs to every till, asking customers to kartenzahlung, bitte. Please pay by card.

I walked down to Museum Island, the cluster of celebrated galleries in the middle of the River Spree. Crowded to bursting on any usual day, it was empty. There are bullet holes in the walls of the Neues Museum, a reminder that the city lay ruined by war in the space of living memory. Nearby there are metal panels in the sidewalk where the Berlin Wall once stood. History lives in every brick here; now we’re living through history.

Berlin’s tourism website offers words of hope: “Our city has survived many crises. Also this time it will go on!” And that’s true, of course. But what will the city of freedom look like once it’s been freed again?

The coronavirus is the threat, but it’s trust that may never recover

Angela Merkel, on her way out, rises again

Johannesburg

The view from Geoffrey York's Johannesburg office.Geoffrey York/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

The high walls and electric fences around my Johannesburg home are a standard feature of South Africa’s middle-class suburbs, designed to shield us from violent home invasions in a country with one of the world’s highest murder rates. But those walls are of little use against a silent and invisible virus. Inside the house, we are trying to prevent the coronavirus from arriving. We are disinfecting surfaces, washing hands and monitoring our temperatures with a thermometer that I first acquired when I visited the Ebola zone in West Africa in 2014. But nobody can seal themselves off from the outside world.

The pandemic in South Africa is following the same trajectory as every other region of the world, although it is still a couple of weeks behind Europe or North America. The total number of confirmed cases has been doubling every two or three days since the first case was reported on March 5.

Traffic in the streets has been somewhat reduced, but Johannesburg is far from being on lockdown. Shops and malls are still open. The city’s Mayor said this week that he “strongly encouraged” the immediate shutdown of restaurants, bars and cinemas – but they remained open. The national government stepped in, ordering taverns to close their doors at 6 p.m. daily and banning any gathering of more than 100 people (or 50 people in taverns), but otherwise there are still few regulations on public spaces.

Similar to most other countries, South Africa suffered a wave of panic buying in its supermarkets as customers began hoarding goods. Most grocery shelves, however, have quickly been stocked full again. Some shops are imposing limits on purchases of specific items.

To keep healthy, I’d like to do a socially distanced solo walk in my neighborhood park. But the city has just announced a new measure: All city parks are being closed.

Africa faces severe economic damage from oil crash and coronavirus

Coronavirus triggers xenophobia in some African countries

The spread of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 continues, with more cases diagnosed in Canada. The Globe offers the dos and don'ts to help slow or stop the spread of the virus in your community.

The Globe and Mail

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article said Gaza is two-kilometres wide, when in fact, it is six-kilometres wide at its narrowest.

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters.