Women take part in a demonstration in New York demanding safe legal abortions for all women in 1977.Peter Keegan/Keystone/Getty Images

One of Lealah Pollock’s patients faced a dilemma. The woman had become pregnant while using an IUD, and already had a very young daughter with Down syndrome. Because she was Catholic, she struggled with the idea of having an abortion.

Dr. Pollock discussed the options with her patient at her clinic in the San Francisco Bay area. In the end, the woman opted for an abortion. At this moment, Dr. Pollock is allowed to discuss reproductive options including abortion with her patients. Soon, under proposed regulations brought forward by the Trump administration, she would not be.

This week, Donald Trump named his pick for a new Supreme Court justice: appeals court judge Brett Kavanaugh. The choice of the conservative, Catholic judge increased speculation about the fate of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 Supreme Court ruling that made abortion legal in the United States.

But, as reproductive-choice advocates point out, the threat to abortion access is already in place, as state legislators attempt to pass ever more restrictive laws, clinics are closed and federal legislation threatens to cut off funding for low-income women seeking abortion referrals.

The threat to low-income women − who make up the majority of abortion seekers − is particularly acute, researchers say. And increasing restrictions at the state and federal levels could mean more women turn to Canada for procedures, support and information.

“It’s frightening to me that the government wants to step into my exam room and tell me what kind of conversations I can have with my patients, especially around what remains a safe and legal medical procedure,’’ said Dr. Pollock, who is affiliated with the group Physicians for Reproductive Health.

Her concern centres on restrictions proposed by the Trump administration to Title X funding – the federal grant program for low-income women – which would prevent doctors from giving abortion information or referrals to women if their clinics receive Title X funds. The proposal, which caused widespread alarm among reproductive health providers, is currently open for public consultation.

That’s just one encroachment. The threats to abortion come in the form of state legislation designed to hamper access – through restrictions on methods and providers – as well as a dwindling number of physical facilities. Currently, there are seven states with only one abortion clinic each, and the last facility in Kentucky is only being kept open by a judge’s order. Ninety per cent of counties in the United States – home to 40 per cent of the female population – have no clinical facilities, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which researches reproductive health issues.

Various state legislatures have introduced laws that put up barriers to a woman’s constitutional rights to abortion. Arkansas passed a bill essentially banning medical abortion (using the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol), which was approved in the United States in 2000. In May, Iowa passed a bill that would outlaw abortion after a fetal heartbeat is detected, generally thought to be around six weeks. Louisiana and Mississippi have passed legislation banning abortion after 15 weeks.

These laws are being challenged in court, but the cumulative effect is to restrict access to abortion at the state level and ultimately at the federal level via the Supreme Court, said Heather Shumaker, senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center in Washington.

“Over the last eight years, since the 2010 midterm elections, we’ve really seen an onslaught of anti-abortion and anti-reproductive health legislation across the states,” said Ms. Shumaker. “And with the Trump administration being allowed to nominate more federal court judges, the anti-abortion movement has felt even more emboldened to pursue unconstitutional legislation.”

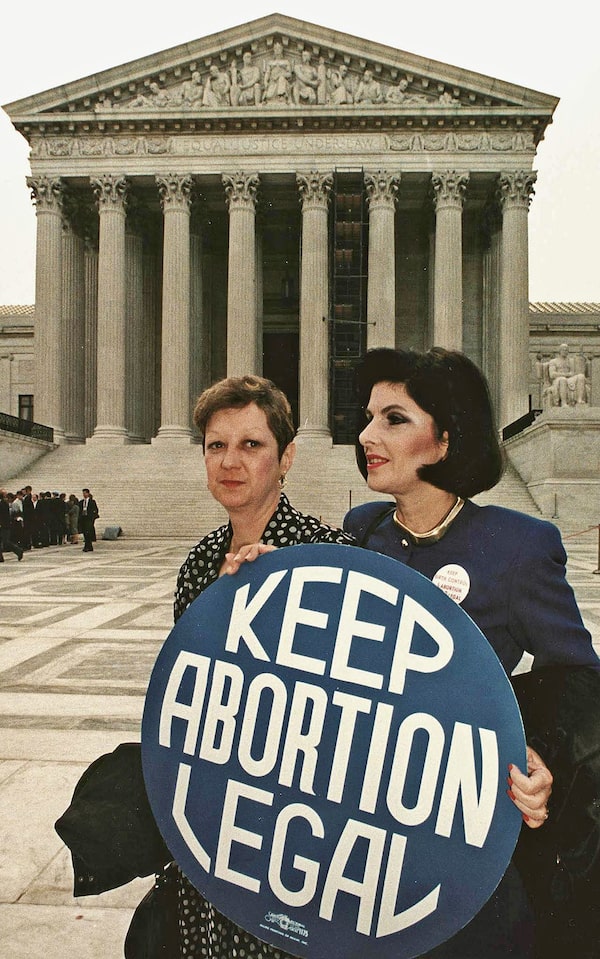

Norma McCorvey, left, formally known as Jane Roe, and former attorney Gloria Allred hold a pro-choice sign in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building April 26, 1989, in Washington just before attorneys began arguing the 1973 landmark abortion decision which legalized abortion in the U.S.GREG GIBSON/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

These laws, she added, “were passed with the hope that they would be challenged. They were direct, intentional challenges to Roe.’’ A number of laws currently before courts, from those that ban abortion methods to those that attempt to impose strict time limits on the procedure, could trigger a Roe v. Wade ruling in the next year or two, Ms. Shumaker said.

The increasing restrictions at the state level do not reflect the wider American sentiment toward abortion: A 2017 Pew Research poll showed that 57 per cent of Americans favoured legal abortion, though that number dropped among certain religious believers. Another Pew poll from 2017 asked if Roe should be overturned: 69 per cent of respondents said no (28 per cent said yes).

While nearly one in four American women will have an abortion at some point in her life, according to the Guttmacher Institute, the numbers are dropping: There were 14.6 abortions per 1,000 women in 2014, down from a high of 16.9 in 2011.

The retirement of Anthony Kennedy, the Supreme Court justice who represented a swing vote on some abortion rulings, provided President Trump an opportunity to fulfill a campaign promise to “[put] pro-life justices on the court.” Judge Kavanaugh will certainly be quizzed on his leanings during his confirmation hearings. One Republican senator, Maine’s Susan Collins, has said she would “not support a nominee who demonstrated hostility to Roe v. Wade.”

In a 2006 Senate committee confirmation meeting, Judge Kavanaugh testified that he would “follow Roe v. Wade faithfully and fully” as a circuit court judge, but wouldn’t elaborate on his personal beliefs: ’“I don’t think it would be appropriate for me to give a personal view on that case.”

The news of Judge Kavanaugh’s appointment drew a crowd of protesters, carrying signs that said “Protect Roe” and “Don’t criminalize abortion,” to the Supreme Court in Washington. Many of them were young women who did not know a time before the Roe ruling enshrined abortion as a woman’s constitutional right. (The right was reaffirmed in 1992, with the U.S. Supreme Court decision Planned Parenthood v. Casey, although the later ruling allowed for greater leeway in state regulation of abortion, so long as those laws did not place an “undue burden” on a woman’s access.)

If Roe v. Wade were overturned, it would have an immediate effect in some parts of the United States. Four states – Mississippi, Louisiana, South Dakota and North Dakota − have “trigger laws” that would outlaw abortion in the absence of Roe. According to the Center for Reproductive Rights, “22 states − nearly all of which are situated in the central and southern part of the country − could immediately ban abortion outright, whereas women in an additional 11 states (plus the District of Columbia) are at risk of losing their right to abortion.”

In other words, should the federal precedent fall, a patchwork of laws would exist across the country, with states on the coast allowing abortion and those on the inside criminalizing it – as well as the women who seek it and the doctors who provide it.

Women are already being charged and jailed in some states for self-inducing abortions. Earlier this year, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists called for this criminalization to end, noting in a statement that, “due to the growing restrictions on abortion access and the closure of facilities providing this service, self-induced abortion attempts may become more common.’’

’’I fear that women’s health will be at risk” if Roe is overturned, said Dr. Pollock, the Bay Area physician. ’If we do end up with a situation where abortion is legal and accessible in some states and not in others, who’s going to be able to travel to those states where it’s legal? Women who have money. Women who have flexible jobs. Women who have access to child care. So really it’s women who are poor, working class, immigrants, who identify as LGBT. Those will be the ones who are most affected by any effort to limit access to reproductive health.‘’

Gearing up for even further restrictions, reproductive choice advocates have been preparing to help low-income or otherwise marginalized women. There are travel networks and fundraisers in place to assist, for example, rural women who may need to travel out of state or even to Canada.

“We can expect that if Roe v. Wade is overturned, there will be an increase in people coming to Canada from the United States for abortion care,” said Jessica Shaw, an assistant professor of social work at the University of Calgary, in an e-mail. “However, this will really only benefit wealthy Americans who can afford travel and the cost of abortion at a Canadian clinic.”

Ms. Shaw is on the board of Women Help Women, an international group that facilitates abortion access in countries where it’s illegal or highly restricted. Last year, the group began a program called SASS, or Self-Managed Abortion, Safe and Supported, to offer advice to women who choose pharmaceutical abortions (34 states require that a doctor prescribe the abortion pill. In 19 states, the doctor must be physically present with the patient, which is seen as a barrier to rural women).

“We have already been supporting people who live in the United States and who have self-sourced abortion medicines,” said Ms. Shaw, “and we will continue to do this regardless of the legal status of abortion in the United States.”