Tsering Dawa arrived in Dharamshala, India, as an exile from his native Tibet in 2021. Very few Tibetans are still arriving in the community where the Dalai Lama and Tibet's government in exile are based.Photography by Ruhani Kaur/The Globe and Mail

Tsering Dawa is that rarest of things in Dharamshala, a new arrival.

Since 1959, when the Dalai Lama fled to India, this small city in the foothills of the Himalayas has been the spiritual and political heart of the Tibetan exile community. Tens of thousands have made the difficult journey here from Chinese-controlled Tibet, risking arrest and even death to escape Beijing’s increasingly stifling controls.

In recent years however, the flow of refugees has become a trickle, as pervasive surveillance and heavier policing have made getting out of Tibet harder than ever. When Mr. Dawa arrived in Dharamshala in March, 2021, he was one of just a handful to make it that year, his appearance so surprising that some suspected him of being a Chinese spy.

Mr. Dawa, whose arm bears a tattoo with his mother and sister's names, says he can sleep more peacefully in exile and enjoys the newfound freedom of religion.

Sitting in his small, one-bedroom apartment beneath a smiling portrait of the Dalai Lama, Mr. Dawa admitted to being slightly underwhelmed by Dharamshala, the town more backpacker haven than twin to the bustling Tibetan capital of Lhasa. Nevertheless, he said there was a “sense of freedom” that he never felt in Tibet itself, an openness and vibrancy that made up for any material shortcomings.

But the Tibetan exile community here is dwindling and in flux, The Globe and Mail found during a visit to Dharamshala in December and interviews with more than 20 people, from government officials and elected lawmakers to activists and recent arrivals.

There are deep-seated political disagreements over the way forward, particularly what will happen following the death of the Dalai Lama, now 87 and pulling back from some public engagements owing to weakening health.

A 90-minute flight from New Delhi, Dharamshala sits at the point where the plains of Himachal Pradesh meet the Himalayas, which loom, grey and snow-capped, over the city’s small airport.

The majority of the local Tibetan community live in the suburb of McLeod Ganj, a former hill station where the British colonial elite used to come to escape the Indian summer heat.

As visitors proceed up the winding road through a pine forest from Dharamshala proper to McLeod Ganj, grey and white buildings give way to the bright yellows, reds and greens of traditional Tibetan architecture.

Some tourists skip the drive entirely, taking a new cable car from the valley to a stop near the Dalai Lama’s temple, surrounded by a maze of shops selling mass-produced, supposedly Tibetan souvenirs.

A busy market in McLeod Ganj, the suburb of Dharamshala where most of the local Tibetans live.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/NECMUULS5FHAHKMPG2ZJJYLNDY.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/WRED3UHM2ZARTGLNAEXJZBHDEQ.jpg)

Tibetans came to Dharamshala in waves. Many fled with the Dalai Lama in 1959, when the People’s Liberation Army finalized Beijing’s annexation of Tibet that had begun eight years earlier. More came in the 1980s, during a period of relative openness when China allowed Tibetans to travel to India to worship and meet with family members. Others fled later repression, until increasing controls made doing so ever more difficult.

“Our parents who came in 1959, they never expected to live, let alone die in India,” said Penpa Tsering, current Sikyong, or president, of the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), the government-in-exile. “They always thought they would go back to Tibet.”

When the Dalai Lama first fled, he called for Tibet’s independence, renouncing an earlier agreement recognizing Chinese sovereignty as made under duress, given PLA troops were at the time already occupying the plateau. As China struggled with multiple disasters in the early decades of Communist rule, there did seem to be a chance Tibet would be able to break away, but by the late 1970s, with Mao Zedong dead and his successors repairing ties with the West, the Dalai Lama changed tack.

In 1979 – based on a comment by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping that when it came to Tibet “except independence, all other issues can be resolved through negotiations” – the Dalai Lama put forward what is known as the Middle Way approach, renouncing independence in favour of “genuine autonomy” within the People’s Republic of China.

This came to seem prescient, as within five years, Mr. Deng endorsed just such an arrangement for Hong Kong, when he proposed the model of “one country, two systems,” under which the then-British colony would become part of China but retain limited democracy and political freedoms.

Multiple rounds of talks between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and senior Chinese officials went nowhere however, and the two sides have not met since 2010. China continues to label the Dalai Lama “a dangerous separatist” and blame him for all unrest within Tibet, despite everything that he says about not supporting independence.

Lhagyari Namgyal Dolkar is an MP in Tibet's parliament-in-exile.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong has transformed from a potential model to a warning of how Beijing’s promises cannot be trusted, after the city’s democratic freedoms have only declined in more than two decades of Chinese rule.

“We have seen how autonomy works under the Chinese Communist Party,” said Lhagyari Namgyal Dolkar, a member of the Tibetan exile parliament. “I fear that our movement has been stalled on this issue for a long time.”

At 36, Ms. Dolkar is one of a new generation of Tibetan politicians and activists who are trying to adapt to a powerful, increasingly assertive China, even as older figures within the exile community continue to speak of dialogue or even the potential collapse of the Communist system.

“We’re talking about complete independence for Tibet because we understand the China of today,” Ms. Dolkar said. “The older generation seem to have no hope or willpower to think we’ll be able to challenge the Chinese Communist Party.”

In the crowded Dharamshala headquarters of Students for a Free Tibet (SFT), a pro-independence group, director Rinzin Choedon said the Middle Way grates for many Tibetans as it legitimizes what they see as the theft of their land.

“When I was in school, a classmate explained it to me simply: He took my pen, and when I asked for it back, he gave me just the cap, saying ‘This is the Middle Way,’” she said. “But what’s ours is ours, they have no right to it.”

Director Rinzin Choedon, middle, discusses strategy with Students for a Free Tibet colleagues Tenzin Lobsang, left, and Tenzin Lakdhen, right.

Both Ms. Dolkar and Ms. Choedon pushed back in interviews against any suggestion there was a split in the Tibetan community on this issue, saying debate is evidence of a healthy democracy.

But they also expressed frustration at how fealty to the Dalai Lama is sometimes used to try and suppress such ideas, even as the spiritual leader has said it is up to individual Tibetans to decide whether they support independence.

CTA officials and older members of the exile community argue that with independence being a complete non-starter for Beijing, Tibetans must compromise in the hopes of reaching any sort of resolution.

“The Middle Way approach is defined by optimism, not defeatism,” said Dawa Tsering, director of the Tibet Policy Institute, a CTA think tank, and former chief representative for the Dalai Lama.

“We have to think rationally. Lots of people are stirring for independence, but it’s not like this stance would bear more results. It’s about rationality, about getting to the negotiating table.”

Penpa Tsering, leader of the Central Tibetan Administration, says there has been 'no traction' with China in more than a decade.

When Penpa Tsering became Sikyong in May, 2021, he vowed to uphold the Middle Way approach, while reaching out to the international community to help push China to resume talks with the Dalai Lama, building on the work of his predecessor, Lobsang Sangay.

“When we do this lobbying, now we have changed the tactic a little bit because China is not responding … since 2010 there has been no traction,” Mr. Tsering said, adding that part of the problem has been that the international community often repeats China’s line on Tibet, legitimizing the illegal annexation of what was formerly a sovereign country. Why would Beijing meet with the Dalai Lama or the CTA, he said, if its control over Tibet is already recognized by the rest of the world?

“The Chinese leadership knows that they have no legitimacy to rule over Tibet and they’re trying to seek that legitimacy from the international community,” Mr. Tsering said.

“If there is anybody who can give legitimacy to the Chinese government, it will be His Holiness the Dalai Lama or the Tibetan people, after reaching an agreement with the Chinese on the future of Tibet.”

In May, 2022, Mr. Tsering visited Canada, where he addressed a parliamentary committee. This earned the ire of the Chinese embassy in Ottawa, which accused him of promoting “Tibetan independence.”

“We do not recognize the so-called ‘Tibetan government-in-exile’ at all and the Chinese Central Government will never negotiate with such an illegal organization,” the embassy said. “Only the Chinese Central Government and the People’s Government of the Tibet Autonomous Region are the representatives of the Tibetan people, and no one else has the right to do so.”

Ottawa largely endorses this line, with the Department of Global Affairs saying Canada “recognizes Tibet as an integral part of the People’s Republic of China with a distinct cultural identity,” while criticizing Beijing’s restrictions on Tibetan culture, religion and language.

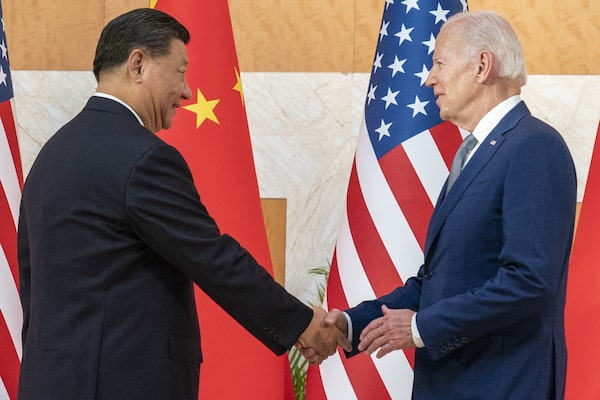

Presidents Xi Jinping of China and Joe Biden of the United States meet at the G20 summit in Bali this past November.Alex Brandon/The Associated Press

Washington follows a similar policy, but a bipartisan group of U.S. lawmakers is pushing to change this. In December, they introduced a bill to the Senate reaffirming Tibetans’ right to self-determination and calling on China to resume dialogue with the Dalai Lama.

“This legislation makes clear that the United States views the Tibet-China conflict as unresolved and that the people of Tibet deserve a say in how they are governed,” Senator Jeff Merkley said in a statement. “It sends a clear message to the People’s Republic of China: We expect meaningful negotiations over Tibet’s status and do not view current Chinese government actions as meeting those expectations.”

In particular, U.S. lawmakers have called on Washington to reject Beijing’s claims – not supported by history or archaeology – that Tibet has been part of China since time immemorial. Endorsing such an assertion is too far even for the pragmatic Dalai Lama, but Chinese officials regard any suggestion otherwise by Tibetan figures as tantamount to separatism, making dialogue increasingly impossible.

Mr. Tsering said that Beijing’s current policy is to “wait for His Holiness to die.” Not only will China seek to control recognition of the next, 15th Dalai Lama – a 2007 law requires government approval for all reincarnations, including when the 16th Dalai Lama will be born – there is no figure in the Tibetan community who has the type of international influence and cachet of the current Dalai Lama, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and one of the most recognizable people on the planet.

Tenzin Lekshay, the CTA’s head of international relations, said this strategy could potentially backfire on Beijing however, as support for the Middle Way approach may wane after the Dalai Lama dies, both among Tibetans and the international community. Countries such as the U.S. that endorsed the Middle Way out of respect for the Dalai Lama’s desire for dialogue may move toward supporting self-determination, as is already the trend among younger Tibetans.

“We do not have the power to tell what the next generation will do,” Mr. Lekshay said.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BIACN4NKVZEMVDN7POKHFJWTSU.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/HSHP5LV7H5AHPESA3UOOW7C3VU.jpg)

Tibetan devotees and monks do their rounds of daily prayers at the temple in which the Dalai Lama normally resides.

That generation will be more international, and more dispersed than ever before, a transformation that brings its own challenges for the CTA and the broader exile community.

From a high of around 150,000 in the late 2000s, the population of Tibetans in India has been halved in the past decade. The number living in Dharamshala is even smaller – around 9,000 – said Kunchok Migmar, the local CTA settlement officer, compared to 20,000 in 2010.

Walking around McLeod Ganj, there is often little to distinguish the hill station from many others across the country, with most businesses run by and catering to Indians, not Tibetans.

Apart from the CTA itself, there are few employers for the exile community, and many young people in particular have moved to bigger cities or abroad in search of work. Even compared to other Tibetan settlements, Dharamshala can feel very out of the way, the isolation that allowed it to be a distinctly Tibetan community now driving people to leave.

“We wish young Tibetans would stay in India and help improve the community, but we cannot force people to live here,” Mr. Migmar said.

Even Mr. Dawa, the recent arrival, who spent years and a large amount of money making it to India – he asked that his exact route not be shared as it may be unknown to the Chinese authorities – is planning to move to Australia in the near future, having fulfilled his desire to see the Dalai Lama in person and share his story of oppression with the exile government.

Dawa Tsering is director of the Tibet Policy Institute.

Inside the quiet, green-roofed headquarters of the CTA, Mr. Tsering said his administration is “learning to meet new challenges under new circumstances.” More CTA functions are being moved online, and the Sikyong said he hoped to change the voting system so it could be more representative of the increasingly spread out, international diaspora. “Dispersal is a challenge, but it’s also an opportunity,” he said. “A lot of younger people are moving out of the settlements to Indian cities or to Europe, North America, Australia, etc., and they’re becoming citizens of those countries. They speak the language, and because of that, they can lobby those countries on behalf of Tibet.”

For years, people have speculated over what will happen when the Dalai Lama dies, the morbid focus on his health equalled only by that which preceded the passing of Queen Elizabeth. His death will likely hasten the transformation of Dharamshala from centre of the exile community to just one of many Tibetan settlements in India and around the world, and whoever is Sikyong when at this point will have to face the challenge.

No matter what happens, Mr. Tsering said, “we have to keep hope alive.”

“If we lose our hope, then the cause itself will die a natural death.”

With reports from Tenzin Dharpo

James Griffiths

James Griffiths