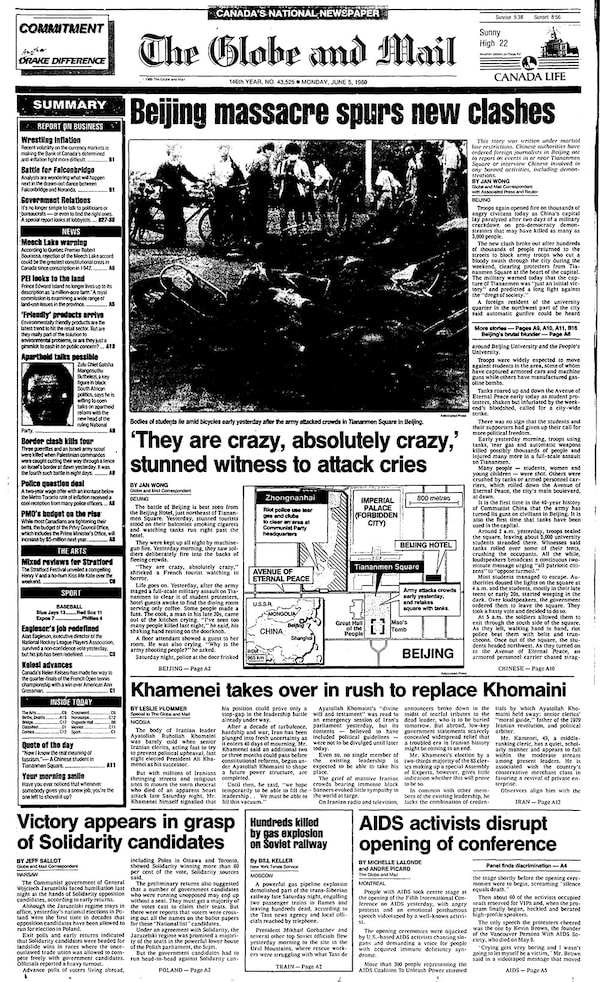

June 5, 1989: Chinese troops and tanks gather in Beijing the day after a military crackdown that ended a seven-week pro-democracy demonstration at Tiananmen Square. Hundreds were killed in the early morning hours of June 4.Jeff Widener/The Associated Press

1989

‘They are crazy, absolutely crazy,’ stunned witness to attack cries

by Jan Wong in Beijing (June 5, 1989)

The battle of Beijing is best seen from the Beijing Hotel, just northeast of Tiananmen Square. Yesterday, stunned tourists stood on their balconies smoking cigarettes and watching tanks run right past the hotel.

They were kept up all night by machine-gun fire. Yesterday morning, they saw soldiers deliberately fire into the backs of fleeing crowds.

"They are crazy, absolutely crazy," shrieked a French tourist watching in horror.

Life goes on. Yesterday, after the army staged a full-scale military assault on Tiananmen to clear it of student protesters, hotel guests awoke to find the dining room serving only coffee. Some people made a fuss. The cook, a man in his late 30s, came out of the kitchen crying. "I've seen too many people killed last night," he said, his shaking hand resting on the doorknob.

A floor attendant showed a guest to her room. He was also crying. "Why is the army shooting people?" he asked.

Saturday night, police at the door frisked anyone who looked like a foreign correspondent. They seized film and videotapes.

The hotel also locked its outer gates, forcing guests to hop over the metre-high fence. By 3 a.m., they locked everyone in. It was just as well, as the troops outside started shooting in earnest.

The hotel is within firing range. Melissa Ennen, a professor of social studies in New York, decided to get down off the roof after a bullet smashed into the neon light next to her. A U.S. tourist standing on his balcony was nicked in the neck by a ricocheting bullet.

From the higher floors of the hotel, there is a clear view of the Avenue of Eternal Peace, and part of Tiananmen Square. This is what the view to a kill looked like.

Early on June 4, 1989, a student protester puts barricades in the path of an already burning armoured personnel carrier that rammed through student lines during the attack on the Tiananmen demonstrations.The Associated Press

The Globe and Mail's front page from June 5, 1989, the day after the Tiananmen Square massacre.The Globe and Mail

SUNDAY

1 a.m. Armored personnel carrier, sounding as loud as a freight train, drives right over a barricade fashioned from an iron fence.

1:04 a.m. Crowds halt the armored carrier in its tracks.

1:18 a.m. Crowds set armored carrier on fire. Two soldiers inside are rescued by student demonstrators.

1:20 a.m. The first gunfire shot, somewhere south of the square.

2:10 a.m. Troops visible on the east side of the square.

2:15 a.m. Much heavier gunfire.

2:16 a.m. Mass panic. Another armored personnel carrier set on fire in front of the Central Committee headquarters.

2:20 a.m. Five ambulances race by.

2:23 a.m. Tanks rumble into square. A lone cyclist tries to race beside one. Truckloads of troops roar by, with soldiers firing indiscriminately at the crowds. Pandemonium.

2:35 a.m. Intense gunfire. A row of soldiers, about 120 abreast, marches across the square, firing at the crowds. Tens of thousands of people run screaming toward the hotel. Some hop over the fence but are turned away at the door.

2:48 a.m. Soldiers have cleared huge swath in the square.

3 a.m. Pedicab furiously peddles past, a wounded man in the back.

3:07 a.m. Shooting right in the square.

3:12 a.m. Heavy gunfire; another mass stampede. More volunteer pedicabs race by with wounded. Other cyclists help clear a path.

3:30 a.m. Crowds try to push buses across the Avenue of Eternal Peace to form a barricade. They fail.

3:45 a.m. Heavy gunfire to the south and east. Another stampede. People run all the way past the hotel.

4 a.m. The lights suddenly go off in the square. People expect the students to be flattened. Some lights are on in the Great Hall of the People. Are China’s leaders watching?

4:40 a.m. Lights go back on in the square. Loudspeakers order students to clear the square, or face the consequences.

5 a.m. The sky is beginning to lighten. Gunfire in the square. Are the students being shot?

5:23 a.m. Dawn breaks. Huge convoy approaches from the east. People desperately try to make a barricade with buses. There isn’t enough time. About 10 bodies on the ground. People still bicycle toward the square.

6:15 a.m. Angry crowd starts chanting, “Strike, strike!”

6:20 a.m. Eleven armored personnel carriers and 15 more tanks come tearing down the west side of the hotel. Some tanks go right through a barricade formed of three earth-movers.

6:52 a.m. People set fire to a second bus, in front of the hotel. Luckily the wind is right. The thick black smoke blows away from the hotel.

7 a.m. Procession slowly carries five bodies by on stretchers. A person at the front holds a Red Cross flag.

8:15 a.m. Soldiers chase people and fire automatic weapons.

9:15 a.m. People set fire to third bus.

9:30 a.m. Crowd growing.

9:46 a.m. People panic and run toward hotel.

10:09 a.m. One shot fired; thousands flee.

10:22 a.m. Soldiers advance eastward toward hotel, shooting into the backs of the people as they flee. Bullets whiz by the hotel balcony.

10:25 a.m. Shooting stops. Twenty bodies lie on the ground. One cyclist is shot in the back, right in front of the hotel. There are two puddles of blood in the parking lot.

10:55 a.m. People approach gingerly, trying to rescue wounded. Soldiers fire again and send them fleeing. Crowd is outraged.

11:22 a.m. Bodies still there an hour later. No ambulances arrive.

11:48 a.m. Soldiers fire another three-minute volley into crowds. Unclear how many hit.

1:57 p.m. Crowd has returned. Soldiers fire again. Unclear how many hit. People scatter.

3:30 p.m. Crowd has returned. Soldiers fire again. Unclear how many hit.

4:15 p.m. Rain starts, crowd disappears.

7:35 p.m. Crowd has returned. Soldiers fire again. Unclear how many hit.

8:50 p.m. Soldiers shoot into crowd for five minutes.

10:35 p.m. Ten tanks and 10 armored personnel carriers rumble down the Avenue of Eternal Peace, occasionally firing machine guns. They roar up and down the main drag like a motercycle gang on Saturday night, to no apparent purpose.

MONDAY

1 a.m. Streets are deserted. But that is more likely because of the thunderstorm than the tanks. A thunderclap brings tourists scurrying out on their balconies. It sounds like mortar fire.

Bodies and bicycles lie crushed beside pedestrian barriers after tanks rolled through Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. This photo and others were smuggled out of China in 1990 and published by The Globe and Mail in 1999 to challenge the Chinese government's denial that protesters were mowed down by tanks and help erase doubts about what really happened that day.

1999

Exposing China’s Big Lie

by Jan Wong (published June 2, 1999)

No one died at Tiananmen Square, the Chinese government declared shortly after the 1989 massacre. At the time, everyone scoffed at the Big Lie. After all, hundreds of foreign journalists and millions of Chinese had witnessed the army shooting its way into Beijing.

There is footage of soldiers firing in the square. There is film of tanks rolling through the streets. There are pictures of the wounded, the dying and the dead. But there weren't photographs of everything. Did tanks really crush the students? As the years passed, some Chinese began to have doubts. Show us the pictures, they said.

Today, The Globe and Mail publishes these pictures, photographic evidence that corroborates oral reports that students were mowed down by tanks on June 4, 1989.

"We have pictures," said a caller to my voice mail late Monday afternoon. I called back. We agreed to meet the next day.

Yesterday morning, a slender Chinese woman in a navy suit arrived eight minutes early. She pulled four black-and-white photos from her shoulder bag. She also had the negatives.

A friend had taken them, she said. She had smuggled them out in 1990, one year after the massacre. Neither she, nor her friend, can be identified. He was a Chinese journalist and remains in Beijing. She is known to be his close friend.

She's a Canadian citizen now. Back in 1989, she was a schoolteacher. She went daily to Tiananmen Square, except for that fateful night. Her friend, sensing there would be trouble, told her to go home. But he stayed, huddling with the students in the centre of the square, at the Monument to the People's Heroes.

Premier Li Peng had declared martial law on May 19. But Beijing residents, by their sheer numbers, had prevented the army from coming into the city.

Now, on the evening of June 3, the troops stormed in from all directions, killing anyone who stood in their way. The first soldiers arrived at Tiananmen Square around 12:50 a.m. June 4. By 4 a.m., they had occupied the square.

The terrified students were allowed to leave by the south end. They straggled westward, then north, heading for their campuses. As they turned onto the Avenue of Eternal Peace, they saw a row of tanks.

"The students shouted slogans: 'Down with fascism! Down with violence!' " the schoolteacher recalled. "They never dreamed the tanks would come from behind." One tank ran over 11 students, killing seven instantly.

I had never understood why more weren't able to escape. The schoolteacher's pictures explain that for the first time. On the far left of one photo, you can see a white iron fence, erected to thwart Beijing's notorious jaywalkers. The students were caught between the tanks and that fence.

"The pedestrian barrier prevented them from scattering onto the sidewalk," the schoolteacher said.

Her friend was one of the last to leave the square. About half an hour after the students had retreated, he also walked out through the south side, in a wide arc that brought him back to the Avenue of Eternal Peace.

That's when he saw the crushed bodies. He happened to have a camera, loaded with black-and-white film from his newspaper. He took a picture with soldiers marching past. He took another, with a tank rolling by.

"He said his hands were shaking, but he just did it. The soldiers were shooting people who took pictures," the schoolteacher said.

That afternoon, the reporter went to his newspaper. He gave the film to the darkroom technician, a friend, who developed it. Many people saw the photos that day – his fellow reporters, several senior editors. They had all been sympathetic to the students. Then the most senior editor spoke up, according to the schoolteacher. "He said, ‘None of you should say anything about these pictures. Just forget about it.’ "

The reporter panicked. The next day, June 5, he slipped out of Beijing with the schoolteacher and two other friends. "The soldiers were still shooting in the street. We felt we were at risk," she said.

They fled by train to a distant province where a friend, another journalist, copied the negatives. The originals remain with that friend. The reporter took the copies back to Beijing.

Other Chinese took photographs, too. But in the ensuing crackdown, some people destroyed them. Others buried them. The reporter mixed them up with ordinary negatives and kept them at home. In 1990, the schoolteacher obtained a visa to Canada. The reporter decided to give her a few precious negatives. She tucked them in a letter, stuck it in a book and carried it onto the plane.

All these years, she has hoped to present them as evidence if Li Peng is ever brought to trial. This week, more than 100 relatives of the dead petitioned Beijing to open a criminal investigation into the massacre. They assert that Li Peng, now the No. 2 leader of the Communist Party and current head of the national parliament, is the primary suspect. Deng Xiaoping, who ordered the army into Beijing, died in 1997.

But the schoolteacher is pessimistic that justice will be served. She decided to come forward on the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre because so many young people question whether it ever happened.

"Look at the new generation," she said sadly. "They only believe the government." She also thinks her friend is probably safe. He was fired as a reporter for his pro-democracy ideas and is now a businessman.

I never thought to tell her that The Globe would pay for the photos. I called her a few hours later. "I will give the money," the schoolteacher said, "to the people in China who are working to find and help the families of the victims."

June 4, 1999: A screen displays an image of the late former Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang speaking to students in 1989 as tens of thousands of people take part in a candlelight vigil at Hong Kong's Victoria Park to mark the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre.Bobby Yip/Reuters

2009

A confident Beijing takes Tiananmen anniversary in stride

by Mark MacKinnon in Beijing (published June 5, 2009)

To stand on Tiananmen Square yesterday, surrounded by hundreds of plainclothes security men clutching dainty umbrellas – watching you watching them – was to witness the absurdity of an unreformed police state mixing freely with the confidence of a rising superpower.

If they hadn't all worn matching red pins on their lapels, the agents, almost all of them male, might almost have passed for businessmen in their golf shirts and sunglasses. But there were other dead giveaways too: Some wore walkie-talkies on their hips, others had tiny earpieces. At the sight of a foreign journalist – or anyone they thought was behaving suspiciously at all – they'd rush into action, demanding identification and using their umbrellas to interfere with photographers taking pictures of a square that is open to the public nearly 365 days a year.

Amid such covert-but-obvious security, none of this country's 1.3 billion citizens dared to so much as lay a flower or light a candle on the square for the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of students, workers and ordinary citizens who were massacred here by their own country's army on June 4, 1989.

Foreign journalists were obstructed and harassed, with crowds of umbrella-wielding agents inserting themselves into yesterday's coverage on BBC World and CNN. Dissidents connected with the 1989 uprising, and some who weren't, were this week jailed without charge or placed under house arrest. Several online discussion forums, including both Twitter and its Chinese equivalent, Fanfou, were blocked ahead of the anniversary.

A young child walks on Tiananmen Square on May 24, 2009.PETER PARKSPeter Parks/AFP/Getty Images

While some see the regime's over-the-top crackdown on any hint of dissent as a sign of weakness, it could as easily be interpreted as a display of its strength. Whether you were standing on Tiananmen Square amid the men with umbrellas, or trying to find information on the Internet around the government's Great Firewall, or watching foreign television channels go blank with every mention of the anniversary, you felt the government's presence and its ability to insert itself into your day. In a very unsettling way, it was impressive.

For all the economic reforms and social progress of the past two decades, it was the Chinese government's sheer, unreformed authoritarianism that was on display. The same political system the students were protesting against is very much in place – overseen by leaders who inherited power from those who directed the Tiananmen crackdown, still willing to go to extreme lengths to preserve their power.

But unlike Deng Xiaoping, who worried the country would collapse if he didn't order his army's tanks and troops to fire on the protesters in 1989, President Hu Jintao and his coterie directed their bloodless crackdown from a position of confidence and strength.

March 13, 2009: Chinese President Hu Jintao, left, chats with his vice-president and eventual successor Xi Jinping as they leave the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.Andy Wong

Twenty years of economic reforms and rapid progress have created a more content citizenry, most of whom wouldn't have protested even if they could. And the country's rising economic strength has blunted the outside world's willingness and ability to challenge China's rulers about how they treat their subjects.

When the United States and other Western countries issued old-fashioned statements about the need for China to repent and confront its ugly past, Mr. Deng's successors made it clearer than ever that they were long past caring what foreign governments think of their political system.

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton issued a strong call for China to “examine openly the darker events of its past and provide a public accounting of those killed, detained or missing, both to learn and to heal.” Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon also called on Beijing to account for those who lost their lives in pursuit of democracy.

But in a week where a Chinese company emerged as the likely buyer of the iconic Hummer automobile brand, and the world looked to Beijing to solve the spiralling crisis over North Korea's nuclear program – not to mention potentially lead the world out of recession – the words rang empty.

Beijing knew it, and responded by effectively telling Ms. Clinton, who had carefully avoided the topic of human rights on her first official visit here earlier this year, that she should know better. “We urge the United States to forsake its prejudices, correct its erroneous ways and avoid obstructing and damaging China-U.S. relations,” Qin Gang, a spokesman for China's Foreign Ministry, told a press conference.

In other words, the rules of the game have long since changed: ‘We're not the backwards state you could look down your nose at 20 years ago. You need us.'

In an effort to remind the world that China is indeed changing, the English-language edition of the state-controlled Global Times newspaper stunned readers yesterday morning with a front-page article that for the first time in years referred to both “the June 4 Tiananmen incident” (though with few details of what happened that day) and the fact the topic remains officially taboo 20 years later. But the article, which highlighted the economic changes over the intervening two decades, was absent from the Chinese-language edition of the same newspaper, and was therefore seen as having limited impact.

“The Global Times is speaking to an international audience and endeavouring to convince that audience that this event is already being re-examined. But there's absolutely no evidence in the more important Chinese-language media that anything like that is happening,” said Russell Leigh Moses, a Beijing-based political analyst. “It's a more sophisticated, but no less strident, effort to show the government is not going to back down.”

The only crack in Beijing's armour was an astonishing crowd – organizers estimated it at 150,000 people – that turned out for a candlelight vigil in Hong Kong's Victoria Park to mark the Tiananmen anniversary. Hong Kong, a British colony until it was reunited with the mainland in 1997, remains the only part of China where free speech is guaranteed and dissent is largely tolerated.

“This rally will tell the world … that we still remember the Tiananmen Square democracy movement,” said Xiong Yan, one of the student leaders of the 1989 protests.

Beijing, however, seemed unconcerned. Mr. Qin, the Foreign Ministry spokesman, made it clear that the government has long since moved on, and doesn’t plan to look back. “Today is like any other day. Stable.”

Tiananmen Square, shown on May 14, 1989 and on May 18, 2019.Catherine Henriette and Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

Tiananmen in 2019: Full coverage

In 1989, China extinguished Tiananmen’s protests – but lit the spark for a religious revival