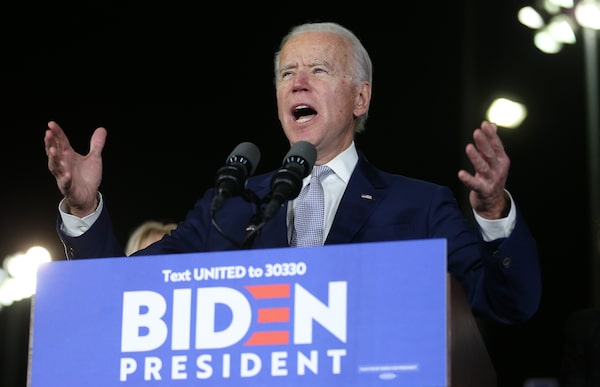

Democratic presidential candidate and former vice president Joe Biden speaks at a Super Tuesday campaign event, at Baldwin Hills Recreation Center, in Los Angeles, Calif., on March 3, 2020.Mario Tama/Getty Images

The empire struck back.

The Democratic political establishment rallied to prop up former vice-president Joe Biden this week, transforming the race for the party’s presidential nomination from a crowded struggle among two dozen competing personalities into a classic two-candidate collision of ideologies. And in a remarkable five-day period, Democratic leaders’ mobilization to deny the party’s greatest prize to its greatest rebel, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, displayed astonishing power.

Mr. Biden’s victory in 10 states demonstrated that his triumph last week in South Carolina was no fluke and established him as a new, formidable force in what could be a protracted fight that might not be resolved before the nominating convention in Milwaukee, Wis., in July. But the Biden surge – he won states such as Massachusetts and Minnesota, where he wasn’t remotely competitive only days ago, and pulled off a dramatic upset in delegate-rich Texas – had the effect of muddying rather than clarifying the Democratic race.

The Super Tuesday results wiped away the consensus of only a week ago – that Mr. Sanders was a force who could not be stopped, with an insurgency of the young who would not be denied. But these results failed to create an updraft for Mr. Biden strong enough to lift him to a clear flight path to the nomination, and they left room for Mr. Sanders to use his showing in the West, where he won decisively, to regain the early delegate lead he assembled but now is endangered.

Super Tuesday: Biden has big night, Sanders takes California as Democratic race narrows

The campaign now takes on a fresh character that is a mirror image of the Republican campaign four years ago – a struggle between the conventional and the insurrectional.

The new factor in the transformed race is the transformed role of Michael Bloomberg, who withdrew from the contest Wednesday morning and endorsed Mr. Biden. That will provide the Delawarean with millions of dollars and hundreds of operatives under long-term Bloomberg contracts. But it may also have the curious potential of proving Mr. Sanders’s decades-long argument that billionaires and capitalists routinely conspire to thwart the will of the people.

“We’re taking on the political establishment," Mr. Sanders bellowed in Essex Junction, Vt., Tuesday night, much the way Donald Trump did week after week in 2016. Mr. Biden, by contrast, is the personification of that political establishment and is the beneficiary of its support and, in recent days, of its funds; in his remarks Tuesday night in Los Angeles, Mr. Biden emphasized that he was, in contrast to the democratic-socialist Mr. Sanders, a “lifelong Democrat.”

It is, to be sure, easy to overinterpret any American primary results, even when they are bunched together in a group of more than a dozen contests. But in this case especially, the Super Tuesday results raised as many questions as answers:

– Which candidates are building and broadening their vote bases? Mr. Sanders is the Mr. Steady of the race; he is retaining his base, but although he did well among Hispanics in California, there is little other evidence that he is attracting support beyond progressives and young people who seek dramatic change in the country. Mr. Biden is building on his support among black voters, which accounted for his victories in Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Tennessee and Alabama, but also built support among white voters in states such as Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota and Oklahoma. Moreover, he displayed strength among suburban women, the voting group that helped deliver the House of Representatives to the Democrats in 2018. Mr. Bloomberg entered Super Tuesday from a standing start but showed no ability to craft a discernible base of support.

— What is the Bloomberg effect? The former New York mayor invested an astonishing US$234-million in Super Tuesday states alone. He said from the start that his motivation was defeating Mr. Trump and that if it were clear he could not win the nomination, he would divert his fortune to someone who could, perhaps the most consequential independent expenditure in the history of American politics. Although he won a handful of delegates on Tuesday, his lone victory in American Samoa served to display his weakness rather than his strength. Now, Mr. Bloomberg has decided that if he can’t be president, he wants to make sure that Mr. Trump no longer is. By joining former mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., and Senator Amy Klobuchar in leaving the race, he hopes to accomplish just that. Ms. Klobuchar’s departure delivered her state of Minnesota to Mr. Biden. Mr. Bloomberg’s departure could deliver enormous resources to the Biden effort.

– Does it matter which states the two leading candidates won? In the drive to win the nomination, a convention delegate is a convention delegate, and it doesn’t matter whether those delegates come from Virginia, which Mr. Biden won handily, or California, where Mr. Sanders prevailed. But if the Democratic preoccupation is victory rather than ideology, political professionals know that the party must win Virginia, which Hillary Clinton carried in 2016, and perhaps North Carolina and Tennessee, which President Trump won. Mr. Biden won all of them. Mr. Sanders triumphed in California and Vermont, but there is almost no chance that the Democrats will lose those states in the November general election.

– Does American political culture react to momentum? The presidential candidate who most famously said that momentum was a factor was George H.W. Bush, who won Iowa in 1980 and declared he had the ‘’big mo.’’ That lasted for eight days, and then Ronald Reagan dominated the remainder of the race. But every contest is different. Exit polls showed that Mr. Biden was far and away the leader among voters who decided late – and those late decisions surely were motivated by his triumph in South Carolina.

– Does it matter who is the front-runner now? Yes, and no. If the consensus front-runner were Mr. Sanders, it would matter hugely; he would continue to be the target of party leaders and moderates who fear that a Sanders candidacy would create a catastrophic loss in November. If the front-runner is Mr. Biden, it doesn’t matter. He still must perform in Michigan and Washington State, among others, next week, and in Florida, Arizona, Ohio and Illinois the following week. This is a contest in which there is frequent talk of political revolution but few signs of reaching a political resolution.

David Shribman

David Shribman