Members of West Virginia's COVID-19 task force work on Jan. 21 at their command centre, a National Guard armory in Charleston. West Virginia, despite having the lowest median income of any state, has given at least one dose to 12.2 per cent of its largely rural population.Kristian Thacker/The New York Times

At a National Guard armoury in Charleston, West Virginia, military personnel hunker down with government officials, business and community leaders to co-ordinate the state’s distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

National Guard troops deliver doses to pharmacies across the state. The pharmacists are paired up with nursing homes and schools to inoculate priority groups that most need the vaccine. Every pharmacy must administer all of its shots within a week of receiving them.

This command centre, formally titled the Joint Interagency Task Force for COVID-19 Vaccine, has proven highly effective. West Virginia has given at least one vaccine dose to 12.4 per cent of its population – the second-highest total of any state in the United States.

It’s a surprising feat for one of the country’s poorest and sickest places. West Virginia has the U.S.’s second-lowest median household income, second-highest rate of obesity and highest rate of opioid overdose deaths. Its 1.8 million people mostly live in small towns amid mountainous terrain. The largest city has a population under 50,000.

“Some of the things that might have been seen as risk factors turned out to be great strengths for our state,” said Dr. Clay Marsh, West Virginia’s COVID-19 czar. “We’re a state that’s small enough, everyone at the leadership level knows each other.”

Stickers for vaccinated West Virginians are on display at the command centre.John Raby/The Associated Press

West Virginia’s success also casts a spotlight on the unevenness of the country’s vaccine rollout. Some states have achieved nearly double the percentage inoculation rate as others. Glaring racial inequalities have also come into play, with only 5 per cent of doses going to Black Americans in a country where they represent 13 per cent of the population.

Some of the outcomes are unsurprising. Small, densely-populated Connecticut is one of the vaccination leaders. Alabama, perennially poor and with a history of government cutbacks, is near the bottom.

But many of the results are unexpected. The state with the highest rate of vaccination, for instance, is Alaska, with a population of 730,000 spread over a landmass more than seven times the size of the United Kingdom, and numerous communities accessible only by sea and air. North Dakota, also small and rural like West Virginia, is similarly near the front of the pack.

President Joe Biden, meanwhile, is boosting the role of the federal government in a bid to speed things up. For him, it’s a political imperative: He has staked his presidency on a promise of controlling the pandemic. For Americans, it’s a matter of life and death. The country most afflicted by COVID-19 has already lost nearly half a million citizens to the disease. Most indicators are currently moving in the right direction, with daily infections down threefold from their 300,000 peak last month. Deaths have fallen from 4,000 a day three weeks ago to 1,300 now.

But with new, more virulent strains of the virus circulating, the U.S. cannot afford to ease up. The country is in a race against time to reach herd immunity before coronavirus mutations outrun the pace of vaccination.

An employee works behind the food counter at the Griffith & Feil pharmacy in Kenova, W.Va., on Jan. 14. West Virginia, which built its own system to administer COVID-19 vaccines through independent pharmacies like this one, now has the second-highest rate of vaccination in the United States.John Raby/The Associated Press

Total COVID-19 vaccine dose

administered per 100,000

As of Feb. 7

9,000

11,000

14,000

17,000

20,000

Alaska

Hawaii

Puerto Rico

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

Total COVID-19 vaccine dose

administered per 100,000

As of Feb. 7

9,000

11,000

14,000

17,000

20,000

Alaska

Hawaii

Puerto Rico

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

Total COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100,000

As of Feb. 7

9,000

11,000

14,000

17,000

20,000

Wash.

Mont.

Maine

Vt.

N.D.

Minn.

Ore.

N.H.

Mass.

Idaho

N.Y.

S.D.

Wis.

Wyo.

R.I.

Mich.

Conn.

Pa.

Iowa

Nebr.

N.J.

Nev.

Ohio

Utah

Ind.

Ill.

Del.

Md.

Colo.

W.Va.

Calif.

Kans.

Mo.

Va.

Ky.

N.C.

Tenn.

Okla.

Ariz.

Ark.

N.M.

S.C.

Miss.

Ala.

Ga.

Tex.

La.

Fla.

Alaska

Hawaii

Puerto Rico

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

What’s worked

At the start of the country’s vaccination drive in December, West Virginia made a fateful decision that would give it an early lead in inoculations: It would be the only state to opt out of a Trump administration deal for CVS and Walgreens, two national drugstore chains, to distribute shots to nursing homes.

Instead, West Virginia set up its own system using the state’s 250 independent pharmacies. In the vaccine war room at the National Guard armoury, representatives of the state’s pharmacy and nursing home associations worked together to pair every long-term care centre in the state with a pharmacist to inoculate its residents.

West Virginia finished vaccinating nursing-home residents by the end of December. CVS and Walgreens, meanwhile, took until late January to finish the job in the other 49 states. By that time, West Virginia had already moved on to inoculating teachers. Now, the state is giving shots to everyone over the age of 65.

“We’re a little more flexible and more in touch with the community,” said Fritz Glasser, who owns three pharmacies in Greenbrier County, in the state’s southeastern corner, and has been helping vaccinate people at the local high school. “We’re glad West Virginia is finally leading in something besides poor health.”

Avoiding the CVS and Walgreens slowdown also helps explain North Dakota’s success. Because of a law that requires most pharmacies to be locally owned, there are only six CVS outlets in the state and one Walgreens. So North Dakota’s distribution to nursing homes was mostly handled by other pharmacies, local health officials and nursing homes themselves.

Nicole Peske, a spokeswoman for the North Dakota Department of Health, said the state also set up a network of providers to inoculate people – including hospitals, clinics, Indigenous groups and public health offices – and began training them months before the vaccine became available. “The NDDoH and its partners … have been actively planning since August for COVID-19 vaccine,” she wrote in an e-mail.

A health-care worker in Albuquerque gets her shot in New Mexico's first round of vaccinations on Dec. 16. UNM Health via AP

New Mexico, which has given at least one shot to 12.3 per cent of its residents, was the first state in the country to create a single online portal where people can sign up to receive a vaccine. The site, vaccineNM.org, uses health and work information to sort people into priority groups, then matches them with a provider to set up an appointment when they are eligible to be vaccinated.

“It’s a first-in-the-nation registration system that saves users the trouble of calling dozens of individual providers to schedule an appointment,” said Matt Bieber, a spokesman for the state health department.

Alaska, meanwhile, is an unusual case. Part of its significant lead in vaccinations – 15.4 per cent of the population – has to do with a statistical anomaly. The state handles vaccines for Indigenous groups provided through the Indian Health Service, and counts them in its total administered doses. In other states, the federal government administers these shots directly and does not count them as part of the state’s total.

But Alaska’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Anne Zink, says there are other things that set the state apart. Because many of Alaska’s remote communities do not have pharmacies, the state previously had to set up a system for distributing flu and measles vaccines. So when COVID-19 vaccines became available, there was already a network in place for dispatching doses far and wide.

This network is as varied as the country’s most sprawling state. In one case, vaccinators inoculated the crews of deep-sea fishing boats when they came to unload their catch on the docks. In another, they used two different planes and a helicopter to reach a remote town on the Bering Sea. In some communities, vaccines are loaded onto sleds and carried from house to house via snowmobile.

“There’s this real sense of community,” Dr. Zink said. “Individuals are finding ways to make it happen.”

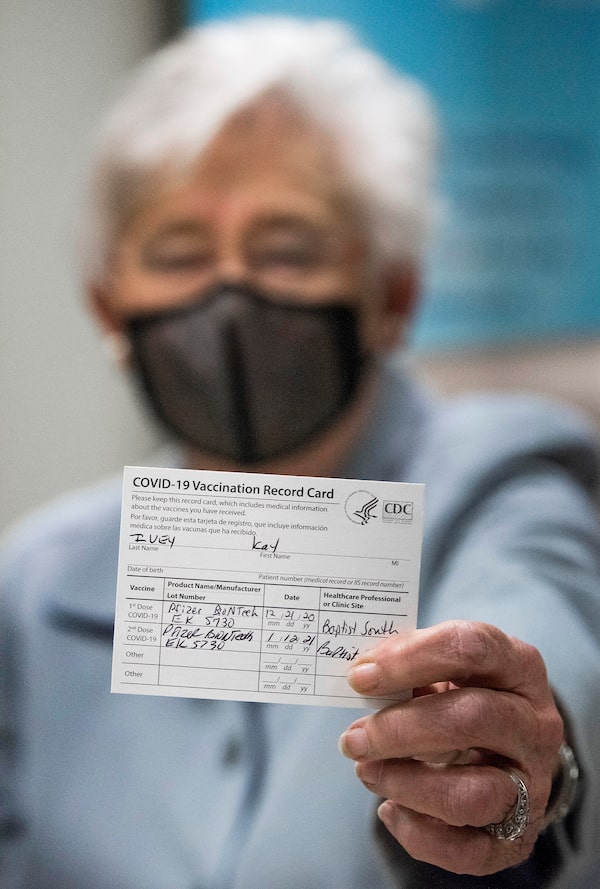

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey shows her vaccine card after getting her second shot in Montgomery on Jan. 12. Alabama is one of the laggard states in U.S. vaccinations.Mickey Welsh/The Montgomery Advertiser via AP

Why some states are lagging

In all of the states at the back of the pack, public health officials have blamed the federal government for not giving them enough doses. Alabama, for instance, has received 17,564 doses per 100,000 people, compared with 21,226 in West Virginia.

But this isn’t the full story. Alabama has administered only 60 per cent of the doses it has received. Missouri, the state with the country’s lowest vaccination rate, has administered 66 per cent. By contrast, North Dakota has given out 91 per cent of the shots it has received, and West Virginia has given out 87 per cent.

Michael Kinch, a public health professor at Washington University in St. Louis, contends that the same lackadaisical attitude that informed the worst states’ response to the pandemic has carried over to vaccine distribution. Missouri’s Republican governor, for instance, was one of the few who refused to bring in a mask mandate. In some towns, local authorities have allowed crowded restaurants to remain open.

The state only set up a vaccine registration portal this week, nearly two months into the vaccination drive. Idaho still does not have such a system, obliging people who want vaccines to call around to individual clinics in hopes of finding one that has shots available.

“At a fundamental level, these folks just don’t understand what is happening,” Prof. Kinch said.

Missouri’s vaccine rollout has been so chaotic that it isn’t even clear to officials who is supposed to be vaccinated. In one incident in Jefferson City, the state capital, several members of the legislature and their staff received shots that were supposed to go to essential workers.

In Alabama, years of budget cuts have decimated the public health system. Eight counties have no hospital, according to a tally by the Birmingham News. One county, Coosa, doesn’t even have a health department; it was eliminated five years ago to save money.

Another problem may be anti-vaccine sentiment. One 2018 study by the University of Idaho found self-described conservatives were less likely to agree to receive vaccines for hypothetical new diseases than liberals were. This was even before COVID-19, and former president Donald Trump’s persistent playing down of the pandemic’s seriousness.

Of the six states furthest behind in the vaccine drive, all voted for Mr. Trump in last year’s election.

Cheryl Lee gets a vaccine shot on Feb. 4 in Federal Way, Wash., where the Swedish Medical Center held a mobile clinic to serve racialized people disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Vaccination rates by racial group vary considerably among states.David Ryder/Getty Images

Ratios of vaccination rates for white vs. minority residents across 23 states reporting vaccination data by race/ethnicity

As of Feb. 2

HISPANIC

Greater disparity

6.0

North Carolina

4.7

Colorado

4.6

Pennsylvania

3.8

Indiana

White residents in North Carolina have been vaccinated six times the rate compared to Hispanic residents.

3.8

New Jersey

3.8

Nebraska

3.5

Mississippi

3.4

Maryland

3.1

Texas

3.1

Tennessee

3.0

Delaware

2.6

Rhode Island

2.1

Maine

2.0

Virginia

1.9

Ohio

1.9

Massachusetts

1.8

Florida

1.7

Oregon

1.5

Alaska

1.3

Missouri

1.0

Vermont

*

Louisiana

*

West Virginia

*Data not available.

BLACK

ASIAN

1.2

2.1

North Carolina

2.6

1.9

Colorado

4.2

*

Pennsylvania

2.5

0.7

Indiana

1.6

3.3

New Jersey

1.7

1.0

Nebraska

2.6

1.2

Mississippi

2.3

1.1

Maryland

2.1

0.7

Texas

2.4

2.1

Tennessee

3.3

1.8

Delaware

1.7

1.6

Rhode Island

1.0

1.0

Maine

2.1

2.1

Virginia

0.6

2.3

Ohio

1.4

1.4

Massachusetts

2.7

*

Florida

1.6

1.0

Oregon

0.9

0.9

Alaska

2.2

1.0

Missouri

2.1

2.1

Vermont

1.7

1.4

Louisiana

1.5

*

West Virginia

*Data not available.

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

Ratios of vaccination rates for white vs. minority residents across 23 states reporting vaccination data by race/ethnicity

As of Feb. 2

HISPANIC

Greater disparity

6.0

North Carolina

4.7

Colorado

4.6

Pennsylvania

3.8

Indiana

White residents in North Carolina have been vaccinated six times the rate compared to Hispanic residents.

3.8

New Jersey

3.8

Nebraska

3.5

Mississippi

3.4

Maryland

3.1

Texas

3.1

Tennessee

3.0

Delaware

2.6

Rhode Island

2.1

Maine

2.0

Virginia

1.9

Ohio

1.9

Massachusetts

1.8

Florida

1.7

Oregon

1.5

Alaska

1.3

Missouri

1.0

Vermont

*

Louisiana

*

West Virginia

*Data not available.

BLACK

ASIAN

1.2

2.1

North Carolina

2.6

1.9

Colorado

4.2

*

Pennsylvania

2.5

0.7

Indiana

1.6

3.3

New Jersey

1.7

1.0

Nebraska

2.6

1.2

Mississippi

2.3

1.1

Maryland

2.1

0.7

Texas

2.4

2.1

Tennessee

3.3

1.8

Delaware

1.7

1.6

Rhode Island

1.0

1.0

Maine

2.1

2.1

Virginia

0.6

2.3

Ohio

1.4

1.4

Massachusetts

2.7

*

Florida

1.6

1.0

Oregon

0.9

0.9

Alaska

2.2

1.0

Missouri

2.1

2.1

Vermont

1.7

1.4

Louisiana

1.5

*

West Virginia

*Data not available.

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

Ratios of vaccination rates for white vs. minority residents across 23 states reporting vaccination data by race/ethnicity

As of Feb. 2

HISPANIC

BLACK

ASIAN

Greater disparity

North Carolina

1.2

6.0

2.1

Colorado

4.7

2.6

1.9

Pennsylvania

4.6

4.2

*

Indiana

3.8

2.5

0.7

White residents in North Carolina have been vaccinated six times the rate compared to Hispanic residents.

New Jersey

1.6

3.8

3.3

Nebraska

3.8

1.7

1.0

Mississippi

3.5

2.6

1.2

Maryland

3.4

2.3

1.1

Texas

3.1

2.1

0.7

Tennessee

3.1

2.4

2.1

Delaware

3.0

3.3

1.8

Rhode Island

2.6

1.7

1.6

Maine

2.1

1.0

1.0

Virginia

2.0

2.1

2.1

Ohio

0.6

1.9

2.3

Massachusetts

1.9

1.4

1.4

Florida

1.8

2.7

*

Oregon

1.7

1.6

1.0

Alaska

1.5

0.9

0.9

Missouri

1.3

2.2

1.0

Vermont

1.0

2.1

2.1

Louisiana

*

1.7

1.4

West Virginia

*

1.5

*

*Data not available.

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

The racial disparities

Debra Furr-Holden, a public health expert based in Flint, Mich., who advises the state on its pandemic response, has an anecdote that illustrates how inequities have crept into vaccine distribution.

A colleague who formerly sat on the board of directors of a local hospital received a call from a friend, an employee of the hospital, when a batch of vaccine doses arrived. Despite being under the age of 65 and not in a priority-vaccination group, Ms. Furr-Holden said, her colleague was offered a shot and accepted it.

The episode demonstrated how people with privilege – more likely to have connections to someone with access to doses – have been cutting the queue.

“I don’t think people are necessarily ill-intentioned, but it is reminiscent of a Black Friday sale, where people trample people at the door,” Prof. Furr-Holden, associate dean for public health at Michigan State University, said. “You don’t realise you’re pushing past somebody’s grandmother or some front-line health care worker or some elderly person with a disability, but that’s what happens when you jump the line.”

Queue-jumping helps explain the near-universal under-vaccination of Black and Latino Americans. Data from the CDC and Kaiser Family Foundation show that out of 23 states that report the race of people vaccinated, only one – Maine – has vaccinated Black residents in equal proportion to their population.

In Pennsylvania, for instance, Black people make up 11 per cent of the population, but only 3 per cent of those vaccinated. In Delaware, the respective proportions are 22 per cent and 6 per cent; in New Jersey they are 12 per cent and 4 per cent; and in Florida, 16 per cent and 6 per cent.

The numbers are similarly poor among Latinos. Hispanic people represent 18 per cent of the U.S. population, but only 11 per cent of those vaccinated.

Washington, D.C., has begun reserving vaccine doses for people who live in majority-Black neighbourhoods after discovering that white residents in the city’s wealthiest areas were disproportionately travelling across town to receive doses at clinics in low-income communities.

Prof. Furr-Holden contends such action is necessary to ensure shots are distributed equitably.

“If we don’t do anything, we drift towards inequity,” she said. “The condition that it be done equitably should be imposed. If people don’t hit the mark, it should impact the number of doses they get in the future.”

Also at play may be wariness of the health care system. In a survey of Black Americans released last week by the National Foundation of Infectious Diseases, 30 per cent of people said they would not get the vaccine. Respondents, particularly those under the age of 44, often said they did not trust health care providers and felt that the system treats people unfairly based on race.

Black and Latino people have been disproportionately hurt by the pandemic, with the death rate among Black Americans nearly three times that of white people.

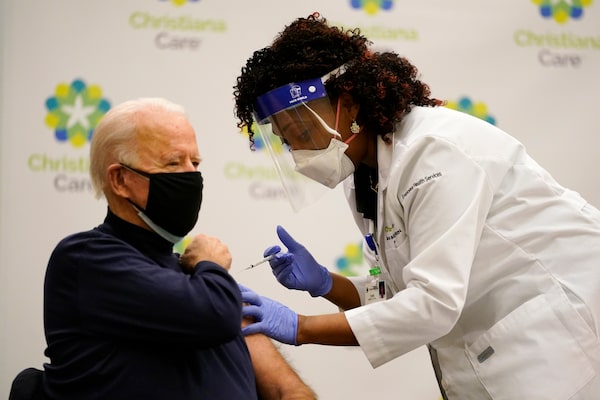

Joe Biden, then the president-elect, gets his first vaccine dose on Dec. 21 from nurse practitioner Tabe Mase at a Delaware hospital. Mr. Biden took office promising the vaccination of 100 million Americans by his 100th day as president.Carolyn Kaster/The Associated Press

U.S. COVID-19 vaccinations

Cumulative doses administered (millions)

Jan. 20

Joe Biden

inaugurated

April 29

Biden’s 100th

day in office

100

Biden’s target

100 million doses

80

60

40

Feb. 9

43.2 million doses

administered

20

0

Jan.

2021

Feb.

March

April

May

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: OUR WORLD IN DATA

U.S. COVID-19 vaccinations

Cumulative doses administered (millions)

Jan. 20

Joe Biden

inaugurated

April 29

Biden’s 100th

day in office

100

Biden’s target

100 million doses

80

60

40

Feb. 9

43.2 million doses

administered

20

0

Jan.

2021

Feb.

March

April

May

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: OUR WORLD IN DATA

U.S. COVID-19 vaccinations

Cumulative doses administered

Jan. 20

Joe Biden

inaugurated

April 29

Biden’s 100th

day in office

100,000,000

Biden’s target

100 million doses

80,000,000

60,000,000

40,000,000

Feb. 9

43.2 million doses

administered

20,000,000

0

Jan. 2021

Feb.

March

April

May

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: OUR WORLD IN DATA

The federal role

The Trump administration poured billions of dollars into vaccine development through Operation Warp Speed and set ambitious vaccination targets. But it mostly left the logistics of distribution to the states to sort out. One major goal, of having all nursing home residents vaccinated by last Christmas, was missed by more than a month.

Mr. Biden, elected on a promise to bring technocratic competence to the U.S.’s flagging pandemic response, is banking that getting the federal government involved in distribution can move shots out faster.

Among other things, he’s started telling states three weeks in advance how much vaccine they will be getting in a bid to improve planning, reimbursed the cost of using the National Guard for distribution and set up a system to directly supply shots to 40,000 pharmacies.

Most visibly, the President has dispatched hundreds of staff from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help build mass vaccination sites.

Drivers queue for the COVID-19 vaccine at the State Farm Stadium parking lot in Glendale, Ariz., on Jan. 11.Terry Tang/The Associated Press

This week, Mr. Biden and Vice-President Kamala Harris held a video tour of one such location, in the parking lot of a stadium in Glendale, Ariz. The site has the capacity to deliver up to 12,000 shots a day, and the White House suggested this approach will be swiftly replicated. “We intend on doing this in many places around the country,” Ms. Harris said.

Still, Mr. Biden has received some criticism. For one, his goal of getting 100 million doses administered within his first 100 days in office is relatively conservative: When the President took power, the country was already vaccinating at a rate of about 900,000 people daily.

And some experts believe that, in his rush to get vaccines out the door, Mr. Biden is making a mistake in not holding back second doses of the vaccine.

Prof. Kinch contends there is a very real possibility that, as a result, some people won’t receive their second vaccine dose within the recommended window of time and have to consequently start the vaccination process over again.

“We have a vaccine with 95 per cent protection. That is unbelievable,” he said. “Let’s not screw it up.”

Vaccines vs. variants explained

Watch: Globe and Mail science reporter Ivan Semeniuk explains how vaccines may not be as effective against new forms of COVID-19, making it a race to control and track their spread before they change the pandemic completely.

The Globe and Mail

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Adrian Morrow

Adrian Morrow