For American politics, it is back to the future – to a 21st-century version of the 19th-century front-porch campaign technique.

Four times in American history have presidential candidates, chary of appearing too ambitious and restrained by the primitive nature of transport in their eras, campaigned for the White House from their homes. These ‘’front-porch” campaigns became a colourful element of the country’s civic life, with hundreds of Americans crowding onto the lawns of candidates such as James A. Garfield in 1880 and even Warren G. Harding as late as 1920 to hear them speak.

This week, with 10 state primaries postponed and the in-person customs of campaigning constrained, former vice-president Joe Biden transformed the front-porch campaign into the living-room campaign, releasing a video recorded from his home in Wilmington, Del., and conducting a virtual press conference on Wednesday. It was his preliminary answer to the question Democrats have been asking from coast to coast:

How does the likely Democratic presidential nominee campaign when his general-election rival, President Donald Trump, is appearing live from the White House to an audience of housebound Americans whose disruption of daily routines have them planted in front of their televisions – and, in effect, in front of Mr. Trump’s re-election campaign?

It is a source of enormous frustration for Democrats – and an enormous challenge for Mr. Biden.

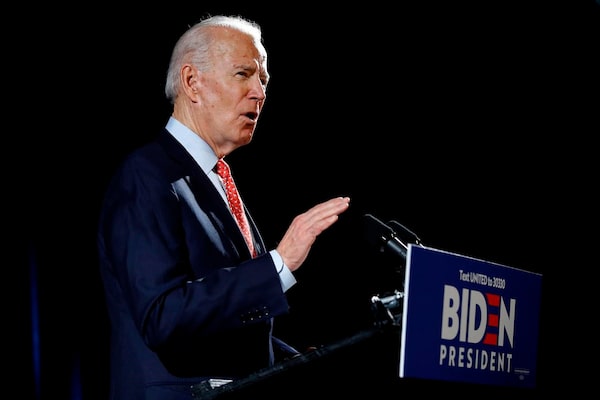

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks about the coronavirus on March 12, 2020, in Wilmington, De.The Associated Press

‘’We’ve got to pierce this,’’ said Jack Corrigan, a veteran Democratic operative who ran the party’s 2004 nominating convention. “But the question is how and when. He’s not been hurt yet. There will come a point when he will have to have a presence.”

It is only one of the conundrums the Democrats face in a political landscape that has been utterly transformed by the coronavirus.

Mr. Biden and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who has not suspended his campaign, are struggling to reach their bases.

Moreover, the party does not know how, or even whether, to conduct its nominating convention in Milwaukee in July. The Biden team also does not know whether the financial slide will affect fundraising.

And there is more: Democrats on Capitol Hill took heat for their skepticism of bailouts for big business. And Democrats who only a month ago were accusing the President of dangerous overreach and near-dictatorial behaviour find themselves in the uncomfortable position of urging Mr. Trump to assume even greater powers. They want him to use authority found in the 1950 Defense Production Act to mobilize American industry to produce mass amounts of vital medical supplies.

It is important that Mr. Biden breaks though without appearing to politicize a national catastrophe, as one top Democratic strategist put it.

Mr. Biden, who has held some online events and a video town hall with Illinois voters, waited to make a broad public statement until his home was fitted for video production, a procedure that Benjamin Harrison (1888) and William McKinley (1896) did not require for their housebound campaigns.

All four presidential candidates who used the front-porch technique prevailed.

“It was the most successful electioneering technique that came and went as fast as it did," said Jeffrey Bourdon, a University of Southern Mississippi historian who wrote a book on front-porch campaigns. “Presidential candidates who tried it never lost.”

In Mr. Biden’s modern-day version – filmed in front of crowded bookshelves – the candidate looked wan and seemed detached from the action.

But his appearance also demonstrated that he was not detached from the emotional toll of the moment.

Far more effective, however, was a video the Biden campaign distributed that showed Ron Klain, former Biden chief of staff, describing the origin of the coronavirus and asking the question, ‘’What did President Trump do?” Mr. Klain, former president Barack Obama’s Ebola response co-ordinator, asked pointedly why Mr. Trump abolished the pandemic prevention response office he created.

But Democratic strategists across the country asked why that message was delivered by Mr. Klain rather than by Mr. Biden himself.

They also expressed frustration that Mr. Trump was dominating the political conversation in an election year – and that, as Daniel Urman, who teaches constitutional law at Northeastern University, put it, political news “is like the high-school sports scores, at the back of the paper.”

The challenge for Democrats is to move politics forward, in newspapers, to be sure, but also in the American conversation. Mr. Biden had a modest digital team until recently, but now is more amply staffed.

“Right now every news story is about Trump,’’ said Mark Gearan, the former White House communications director for Bill Clinton who now directs the Institute of Politics at Harvard University. “It’s a moment for the media to give him some space as well. People are thirsting for information, and it’s an opening for political leaders like Biden if they can figure out how to use it. And the key is to personalize it: ageing parents, school kids at home. It’s Joe Biden’s strength – if only he can be heard.”

David Shribman

David Shribman