To paraphrase Dr. Johnson, the imminent loss of a lease can concentrate the mind wonderfully. For proof, pay a visit to the just-opened TBD exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in downtown Toronto.

MoCCA has been housed since January, 2005, in a 990-square-metre repurposed textile factory directly north of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health on Queen Street West. By and large, it has been a happy stay, one that’s helped make the not-for-profit museum a well-regarded cultural fixture locally and nationally. However, its landlord, a consortium of developers, has let MoCCA, which houses a permanent collection of approximately 400 works by more than 150 Canadian artists, know its lease will expire on Aug. 31, 2015. And so the search is on for new digs, better, bigger digs, it’s hoped.

This looming change of fortune is stressful, of course. Existential even. In the meantime, it’s provided a wonderful curatorial opportunity for Su-Ying Lee, MoCCA’s assistant curator since January, 2013. She’s the brains behind TBD, a thought-provoking group show – part rumination, part conversation, part interrogation – on the form, function and future of the contemporary art institution, and our presumptions and assumptions about it. Lee, 45, is an artist herself, known for doing collaborative projects in unlikely situations or circumstances – a revolving door at Toronto’s Metro Hall, a former storefront, the laneway behind her home in Little Portugal. It’s an aesthetic – whimsical, refractive, DIY – that works well here.

TBD is commonly used as the acronym for “to be determined” – an apt descriptor for MoCCA’s circumstances, both currently and in the near future. But like any acronym, TBD prompts other constructions, many of which will surely come to minds of visitors as they peruse Lee’s concoction.

“To be destroyed,” for one, “To be deconstructed,” for another, “To be developed,” “To be discussed,” “To be decided,” “To be decontextualized” – Lee’s TBD gives space to them all in the endangered place that is MoCCA which, as she notes, is having to contend with “the preoccupations of real estate and architecture” that have been such a part of the modern art world the past 20 years.

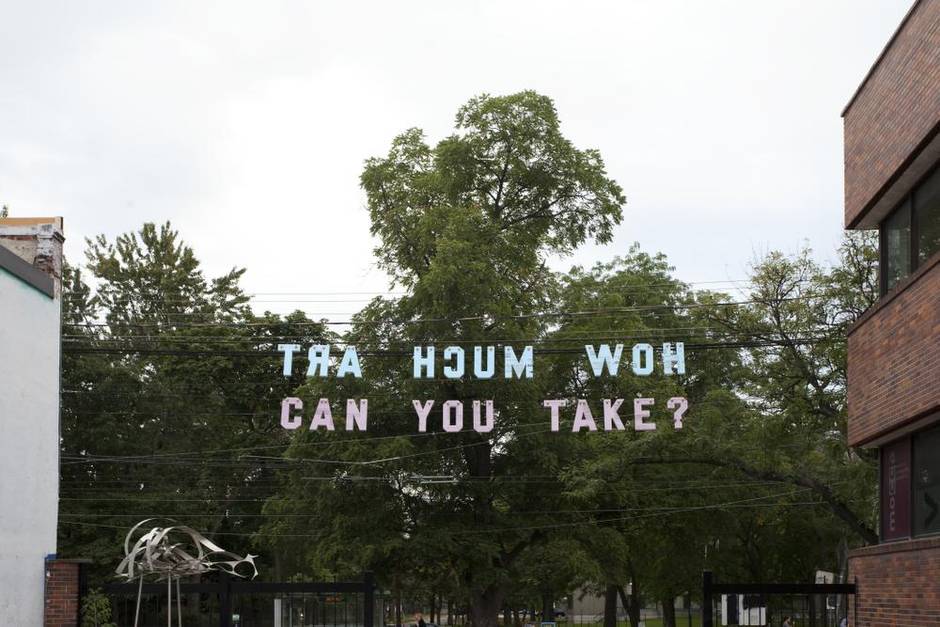

The audience for art is indubitably larger than ever. But the experience of that art often has been about anxiety and intimidation as much as pleasure – a circumstance Lee addresses at once outside MoCCA’s physical plant with the installation of a sign, by Toronto artist Jesse Harris, reading: “How Much Art Can You Take?” The polystyrene letters are strung across MoCCA’s courtyard/parking-lot entrance like the signage found at a used-car lot, the words at once invitation, promise and threat (as in, “Do you have the nerve to cross this courtyard to see a lot of so-called art that likely won’t look anything like the Mona Lisa or Norman Rockwell?”).

They’re also a query/challenge to the community at large since MoCCA’s neighbourhood was once one of Toronto’s grittiest and bedraggled. The irony, of course, is that MoCCA’s presence has, along with the arrival of other art galleries and renovated hotels, restaurants, expensive clothing stores and condominiums, contributed to a gentrification/revitalization that is driving MoCCA if not out of existence then out of its current habitat – a habitat Vogue recently rated the second-hippest district in the world.

Indeed, MoCCA’s departure is only the other side of the creation “myth” of the public art museum. As one U.S. critic has observed, the museum comes into the world as just one more “reflection of the social order – with modes of display (and the objects housed therein) steeped in both the ethos and the economy of the day” – and it leaves that way.

Lee further addresses the accessibility/intimidation issue by offering two lobby entrances to the exhibition. The first is the formal doorway with heavy pull handles that’s always been there, mediated by a large reception desk. Take this route and you encounter the ephemera usually associated with an exhibition – the title wall, the names of the artists in the show, the introductory didactic wall panel, tips-of-the-hat to various sponsors.

However, to the east of this, Lee has cut an opening into the lobby wall, free of doors, that allows the viewer direct access to the main gallery without any of the narratives and rites of passage associated with an official entrance. This opening, moreover, aligns with MoCCA’s main entrance, a glass door, thereby permitting Queen West passersby a direct sightline across the courtyard and into the interior space.

No matter what entrance you use, however, you will be counted, registered, in fact, on a display counter in the lobby. Attendance, of course, is one of the most important metrics for the contemporary art museum; it sometimes seems the primary index of a show’s significance, an institution’s worth and a government’s level of support. To spoof this “quantity-as-value” convention, Toronto artist Jon Sasaki has devised a “performance” to double MoCCA’s visitations during TBD’s seven-week run. Once a week he’ll visit the museum and note the total number of visitors in that duration. If it says 200 patrons have visited, he’ll proceed to go in and out of MoCCA 200 consecutive times: Et voilà, a doubling of official attendance!

Often, visitors to a contemporary gallery are mystified (or at least intrigued) as to why it’s devoting precious time and space to one artist or a group of artists and not another. How has this privilege come about? In his TBD presentation, Toronto conceptualist Bill Burns intimates that semi-divine forces (a.k.a. curators and collectors) may hold the answer. He has installed two model constructions, one of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the other of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the exterior of the Pompidou holds a gigantic billboard reading “Hans Ulrich Obrist/Priez Pour Nous” while a billboard on SFMoMA declares: “Steven Cohen/Watch Over Us.” Affixed on a wall beside these models is the model of a yellow-and-green Cessna airplane pulling a banner reading “Beatrix Ruf Pray For Us” (it is, in fact, a small-scale replica of a stunt Burns did last year with a real Cessna at Art Basel Miami Beach).

Burns’s invocations of intercession are an art-world in-joke – Obrist and Ruf are influential, career-making European curators, Cohen one of the world’s biggest-spending art collectors – but they speak to the church-like status of art institutions in our secular age, the brand power of names and Burns’s own desire to both twit and be recognized by the charmed circle of the international art world.

TBD is full of such provocations – there are more than a dozen “interventions,” installations and works by artists from Vancouver, Los Angeles, Madrid, Rotterdam and Stockholm – all in the service of destabilizing our fixed notions of how the art world works. One of the most interesting is the “wall of ideas” on MoCCA’s northern interior perimeter. It’s the result of an open call Lee made earlier this year to architects worldwide, seeking proposals to reimagine galleries and museums “once our existing ideas about them are destroyed.” Submissions totalled more than 130 from which a jury chose 69.

Predictably, most are on the blue-sky side: One urges MoCCA to “divorce itself from the archaic model of having a permanent venue” and instead embrace “the fluid essence of contemporaneity” by using “an ever-revolving roster of locations in Toronto and beyond.” Others are funny, like the one that envisages MoCCA hosting exhibitions in a giant disc hoisted above ground by a mobile crane (the crane operator would also serve as museum director and, as such, would have to have an MFA degree, 10 years’ experience in the culture sector and at least 100 proven hours’ working a crane).

Lee thinks MoCCA 2.0, whenever it’s birthed, wherever it’s berthed, will be distinguished by “a return to the space we know” – a fixed structure, in other words, with four walls, a ceiling and floor. It’s a view shared by Vancouver-trained, San Francisco-based architect Andreas Mede. In fact, “as cultural literacy weakens, as all expressions are accepted as ART, as critique no longer exists,” it’s the museum that “will remain the point of discussion,” he writes in his contribution to the wall of ideas. “A wall, a roof, a window and light. Simple, raw, adaptable.” Talk about “itinerant galleries” and “mobile units” is all so much empty theorizing: “The future has been – the past is to come.”

TBD runs at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, 952 Queen St. W. in Toronto, through Oct. 26 (mocca.ca).