Hear the word “Islam” these days and, for many, visions of beheadings, demagogic mullahs, hollow-eyed refugees and gun-toting jihadis are almost sure to follow. While hardly fair or truthful, this mental slide show is nevertheless an understandable result of the way Islam, or at least acts perpetrated by some in the name of Islam, is portrayed via the 24/7 news cycle.

It was something of a balm, then, to visit the recently opened Aga Khan Museum in North Toronto the other day for a tour of its newest exhibition. The Lost Dhow: A Discovery from the Maritime Silk Route presents more than 300 artifacts from a cache of more than 50,000 recovered in 1998 from the remains of a ninth-century Arab dhow found at the bottom of the Java Sea. The discovery, initially made by two divers looking for sea cucumbers near Indonesia’s Belitung Island, prompted international headlines. It provided both the earliest and the most substantial physical evidence of a robust system of trade between the Muslim Abbasids, whose empire included parts of Iraq, Iran, Egypt and central Asia, and China’s Tang dynasty, whose reach stretched from China to Iran.

The artifacts in the show – all from the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore, which holds the full dhow cargo – are compelling, often beautiful, their almost pristine condition due to the anaerobic conditions created by the silt covering the wreck site. But what’s also edifying is the subtext underpinning all the bowls, vases, copper-alloy mirrors, cups and boxes: that of an outgoing, confident religion-culture actively engaged with the world, shaping and being shaped in turn, sharing ideas and technology as well as things.

“This isn’t stuff being shipped across the world on spec; this is stuff being made specifically for exchange and sale … for both mass-consumption and specialty taste,” notes John Vollmer, the New York-based guest curator of the exhibition. “This stuff makes it very clear that communication was occurring at a very sophisticated level.” (A round-trip by sea back then could take as many as three years.)

“This exhibit,” he adds, “reminded me of a thing I learned in university [Harvard and University of Toronto]: When the Abbasid Empire was established [after 750], the caliph built the [House of Wisdom] in Baghdad, gathering all the written literature of the world, translating it into Arabic. We wouldn’t have Aristotle, we wouldn’t have Plato, without that.”

The vast majority of the artifacts recovered from the shipwreck were of Chinese origin, proof that the dhow was sailing back to the Persian Gulf, perhaps to Siraf or Basra, with likely stopovers en route to trade in ports in the Kingdom of Srivijaya and southern India. The dhow was not large – the Aga Khan Museum has helpfully traced its shape and size, 15 metres long by six wide, on the gallery floor – but its cargo was huge, filling every nook and cranny, weighing more than 20 tonnes. Included in the exhibition are several of the huge jars that, when opened, were discovered to contain more than 50,000 Changsha bowls, named after the kilns in Hunan where they were produced.

The Aga Khan Museum displays about 130 or so of these small bowls, which, though handmade, clearly demonstrate the Chinese were adept at mass production centuries ago. What’s also fascinating is how creators would occasionally personalize their wares: One bowl, for example, is embellished with a cartoon of the head of an Arabic male, complete with beard and curly hair; another has Chinese characters providing a brief autobiography of the artisan; yet another’s calligraphy turns out to be a poem.

Also included in the show are three dishes with blue flourishes on their glazed white surfaces. They’re significant for two reasons – as early, fully intact examples of now-common Chinese blue-and-white ware, and as markers of Chinese-Islam interaction 1,200 years ago. The use of blue on white ceramics originated, in fact, with Iraqi potters importing cobalt from Iran. These artisans, it’s believed, had learned techniques in pigmentation, glazing and firing from their Chinese counterparts, while the Chinese later experimented with raw cobalt shipped from the Middle East to get the blue effect on their porcelains, sometimes emulating Arabic motifs.

The Aga Khan show has bling, of course, including eight wonderfully preserved silver boxes, their covers festooned with lyrical images of deer, birds, bees and ibexes. These likely were used to hold cosmetics, incense, rare spices, perhaps medicines. Most spectacularly, there is a large, octagonal-shaped cup made from one pound of pure gold, its exterior chased with reliefs of Chinese dancers and musicians.

The exhibition’s signature piece is a bulbous ewer – roughly a metre in height, it’s the largest ceramic recovered from the Belitung wreck. It certainly looks great, especially the green dragon head that forms its lid and spout. But how functional is it? Not very, according to Vollmer: “You’d need a very tall servant to make it work.”

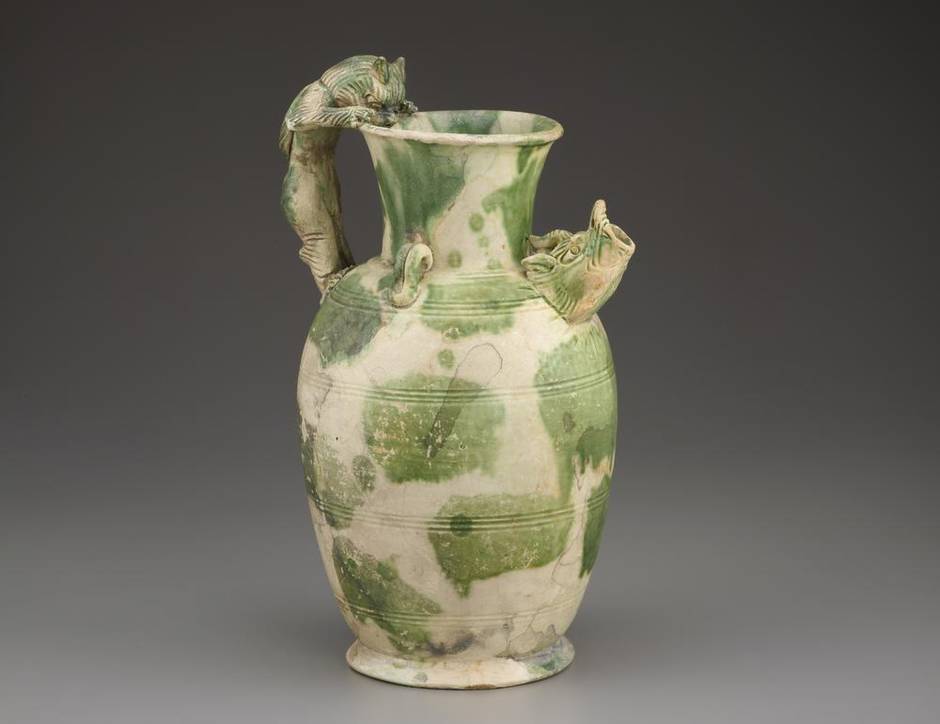

More charming is a smaller, green-splashed ewer, this one about 30 centimetres high. Two elements account for its appeal: the handle, which is shaped like a lion, its jaw and paws clamped to the ewer’s rim; and the spout, a cartoonish dragon head. Equally charming – indeed, charm is its sole function, unless it was used as a paperweight – is a novelty figurine of an Akita or chow chow, its tail like a comma, the face the soul of friendliness.

The Lost Dhow is a calm, quiet show that encourages an engagement at once relaxed and attentive. It’s about “the testament of the object” and another demonstration of this still-young museum’s determination to educate audiences in the aesthetics and worldliness of Islam.

The Lost Dhow: A Discovery from the Maritime Silk Route has its North American premiere Saturday at the Aga Khan Museum, 77 Wynford Dr., Toronto, and runs through Apr. 26, 2015.