We’ve been told for a long time that good artists break rules. But even in the most Oedipal art practice, the one most scornful of the last generation’s commandments, there’s some kind of stricture about what can be done on what surface. Rules can be the ropes that define the boxing ring where the artist goes as many rounds as necessary, with no permission to step out of the ring for help.

As it happens, the first of her works that Julia Dault chooses to show me is a sculpture bound together with boxing tape, the kind prizefighters use to wrap their hands. She made the piece in The Power Plant gallery at Harbourfront Centre the day before we talked, wrestling big sheets of Formica into wide shining loops, then trussing them into a heap with the boxing tape and cord used by gaffers to hang lights. It sounds like awkward, sweaty work, and the Toronto-born artist did it according to her own strict rules.

“I can’t use glue or screws, or pre-heat or bend anything in advance,” she says. “It all has to be done on the site, because part of it is about making and thinking simultaneously in the space. And I can’t have help. It’s me and my capabilities versus it and its characteristics. If I had help, it would throw off the balance of forces.”

Right now, forces in Dault’s art and life are propelling her toward a significant international career. A mere six years after she emerged from art school, her work is known, shown and bought in London and New York. Her Power Plant exhibition, the opening show of the season, is a homecoming of sorts for an artist whose current base is the launching pad for many creative careers – a studio in Brooklyn.

Dault’s self-imposed rules for sculpture definitely kick against the standards of a previous generation of minimalist sculptors (Donald Judd for one). They wanted a pristine surface, sometimes fabricated by hired artisans; she wants you to see the scratches where she dragged or bent the material. They wanted joints and installation supports to be invisible; she points to the knotted cord that lashes her sculpture to the wall.

“It’s about how you get the hand back into the process, and yet maintain the kind of industrial minimal aesthetic that I’ve always adored,” she says. “It’s about evidencing the hand in the action. On closer inspection, you can start to discern where that labour took place.”

The experience of looking at the sculpture Dault is showing me ideally includes a bit of detective work, as you try to figure out what happened in the three hours and 15 minutes Dault spent building it. That’s another of her rules: Every sculpture has a date and time stamp, like the stickers supermarkets use to show when the butcher hacked up the meat.

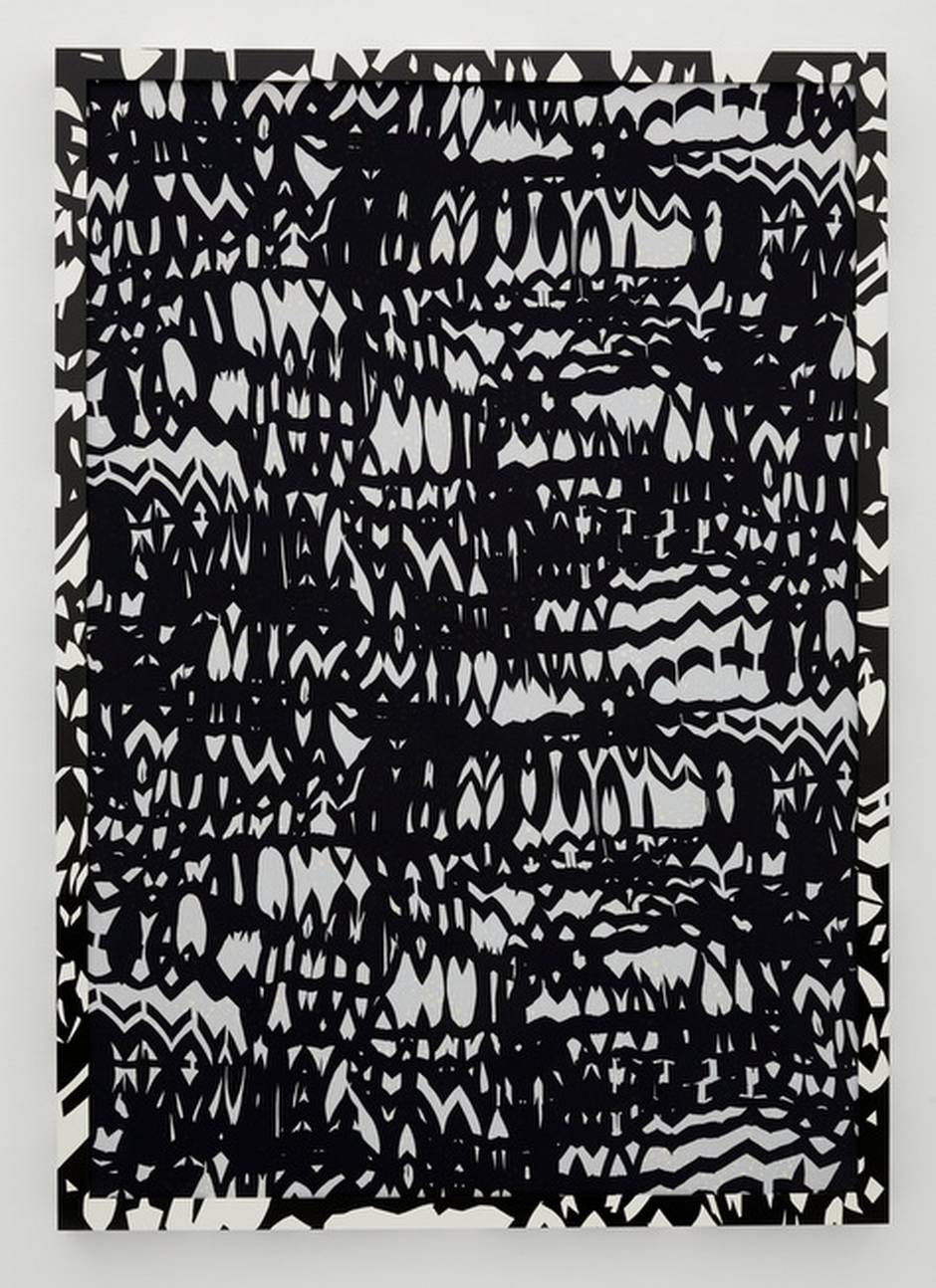

The idea of leaving signs of action on the work is even more evident in Dault’s paintings. Her rules for painting are more like uniform procedures she can bend if she chooses. Typically she paints several layers, some of them wildly colourful or patterned, then covers those with a single-colour layer. While that top coat is still wet, she scrapes some of it away with rubber combs and other tools, partially revealing what’s underneath.

You end up peering through a hand-made irregular lattice of paint at a surface that is both abstract and subtly three-dimensional. It has depth even without figure or perspective. For a couple of pieces in the Power Plant show, Dault includes a layer of cutaway spandex or pleather, always found or bought, never custom-fabricated. Unlike the sculptures, which are always made on site in one session, the paintings are done over a period of days or weeks in a studio.

Dault’s sculptures are all called Untitled and given a number; she made Untitled No. 1 in 2008 as a thesis piece at New York’s Parsons The New School for Design. The paintings all have names, such as Iron Maiden and Lady Danger – pop cultural names, mostly. “Abstract painting is so often an untouchable realm to get to some other place, but it’s important to me that it be about the everyday,” she says. “A title helps bring it back down to a more accessible place.”

There’s nothing overtly autobiographical in Dault’s work, though it’s easy to see lines of influence in her upbringing. Her mother was a high-school art teacher, and her father is Gary Michael Dault, an eloquent veteran Globe art critic.

The home milieu may have made it easy for Dault to absorb a rule now pervasive in the art world, that an artist should be very articulate about their practice. You can’t get by, as J.M.W. Turner did, with a quip like “painting is a rum thing.” Dault’s patter about what she does is as smooth and rational as if she were explaining a system of philosophy. She took an unusual route to get such clarity about her work.

“I thought I didn’t know enough about the world to put stuff in it,” she says, “so I studied art history to find out more. Then I thought I needed to learn how to write and think about contemporary practice.” So she became an art critic, writing about the work of others for The National Post and other publications. It was only after 10 years of reading, writing and sharpening her wits that Dault went back to school to pursue her real ambition: to become an artist. She was 30 by the time she graduated in 2008.

She had been painting all along, abstract expressionist canvases she says she would never show. “They were large and gestural and great to make. They were very formative for me. I needed to get them out of my system.” Her rules and procedures are partly a way of controlling and defending herself against that ab-ex influence, and against the austere sculptural minimalism that she also loves.

In the end, however, a rule is not a recipe. Dault’s paintings have a playful spirit; her imposed limitations leave room for spontaneity. The light in any given gallery may help shape the sculpture she builds there. If rules imply a game, there are many more moves left in the art games devised by Julia Dault.

Julia Dault’s exhibition, Color Me Badd, runs at the Power Plant Gallery Sept. 20 through Jan. 4.