As Drawn & Quarterly turns 25, the Montreal comics publisher is more successful than ever, boasting a growing staff, a thriving bookstore and an all-star roster of talent. But it's also a time of transition, with the company's beloved founder stepping back to concentrate on his own cartooning. Mark Medley tells the story of how a former bicycle courier created Canada's finest independent press – and the best comics publisher in the world

Drawn & Quarterly is throwing a party; they just need to find somewhere to hold it. Julia Pohl-Miranda, marketing director for the Montreal publisher of comic books and graphic novels, has been trying, thus far in vain, to reserve a Toronto bar or restaurant to host their afterparty for the Doug Wright Awards, which honour the best in Canadian cartooning. It’s a rainy afternoon in mid-April, and the event is a little less than three weeks away. Making matters more difficult is the dearth of venues near the Toronto Reference Library, epicentre of the Toronto Comic Arts Festival, which takes place this weekend.

The festival, being held for the 10th time this year, is one of D&Q’s most stress-inducing events. The 2015 edition will be even busier than usual. A record number of the company’s authors are attending the festival, which has gone so far as to set aside a dedicated space for D&Q events. This weekend will also see the launch, on the occasion of D&Q’s 25th anniversary, of a jaw-dropping 800-page, full-colour anthology that serves as both company history and testament to everything accomplished since its first title – a modest black-and-white 32-page offering – arrived in comic-book stores in the spring of 1990. Since it was founded by Chris Oliveros, Drawn & Quarterly has been as responsible as any publisher for influencing the public’s understanding, appetite and acceptance of comic books.

The anthology’s publication, coupled with this weekend’s TCAF festivities, also mark the end of an era: Oliveros is stepping down as publisher and editor-in-chief to focus on his own comics career, leaving the future of D&Q in the hands of two long-time employees. It’s the most significant change in the history of a company that now boasts an all-world stable of cartoonists and one which, over the past quarter-century, has become not only the pre-eminent comics publisher in Canada (and maybe the best publisher, full stop) but one of the best comics publishers in the world.

“This might sound a little grand, but I think it can be backed up with facts,” says Adrian Tomine, an American cartoonist who has been publishing with D&Q for 20 years. “Chris is someone, even if he was to just completely disappear from the world of comics now, who could go about his life thinking he had literally affected the world, in a way. That he had been a major part of how comics are viewed in our society.”

The perception of comics has drastically shifted since D&Q was founded in a Mile End apartment all those years ago. And yes, Avengers: Age of Ultron dominated movie theatres last weekend, Marvel controls the most lucrative film franchise in the world, and the most-watched series on cable is a comic-book spinoff. That is not Drawn & Quarterly.

Instead, the company’s own rise has run parallel to the form’s surging mainstream popularity, the art-house cinema to Marvel and DC’s blockbuster factory, forging an identity that embraced high-end design and a distinct visual vocabulary, almost akin to poetry, one that found drama not in capes and cowls but the introspective and often the autobiographical, whether the search for a forgotten cartoonist or a middle-aged man’s warmhearted relationship with sex workers.

“I think it’s hard to see how important they are historically, but all you have to do is imagine them not existing,” says the D&Q cartoonist Lynda Barry. “When anybody talks about the history of comics in North America, they’re going to talk about Drawn & Quarterly.”

‘The company always was on the brink of bankruptcy’

Postponing party planning for later, several members of the D&Q team gather in a corner of their eighth-floor office, next to the railyards in the city’s Mile-Ex neighbourhood, to discuss the future. It’s a small, open-concept space – almost every inch is put to use – and the meeting is held around the closely positioned desks of Oliveros, associate publisher Peggy Burns and creative director Tom Devlin, who are joined by Pohl-Miranda, who started as an intern in 2008, and managing editor Tracy Hurren, who was been with the company for five years. To a visitor it’s a rather charming workspace, crammed full of comics and artwork and mementoes from the past three decades, but the office, carved out of an old warehouse, has its quirks, and the company is moving to larger premises in June.

“If the coffee maker’s on, and we try to boil water, we’ll blow a fuse,” explains Hurren after I ask about the flickering lights.

Over the next hour, they scrutinize the editorial lineup for the remainder of 2015 and 2016, a slate of books that includes new offerings from D&Q faves Lisa Hanawalt, Leanne Shapton, Tom Gauld, Seth, Keith Jones, and Chester Brown’s Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus, which Burns describes as “prostitute Bible stories.”

“I’ve never seen a period that was more fertile than the one we’re currently in now, in terms of the number of really exceptional talents working,” Oliveros, a soft-spoken 48-year-old, tells me later.

Although the company now has 19 employees, many of whom seem to juggle multiple roles, for much of its existence D&Q was, essentially, a one-person operation. Oliveros, a born-and-bred Montreal anglophone who had been working as a bicycle courier, founded the company in 1989, though the first issue of the titular comic (Marina Lesenko, his now-wife, suggested “Drawn & Quartered”) was delayed until the following April after a printing error led to the pulping of all 7,000 copies. Before launching D&Q he’d worked on a short-lived comics anthology called Core; blaming “youthful naivety,” Oliveros felt he could do better on his own.

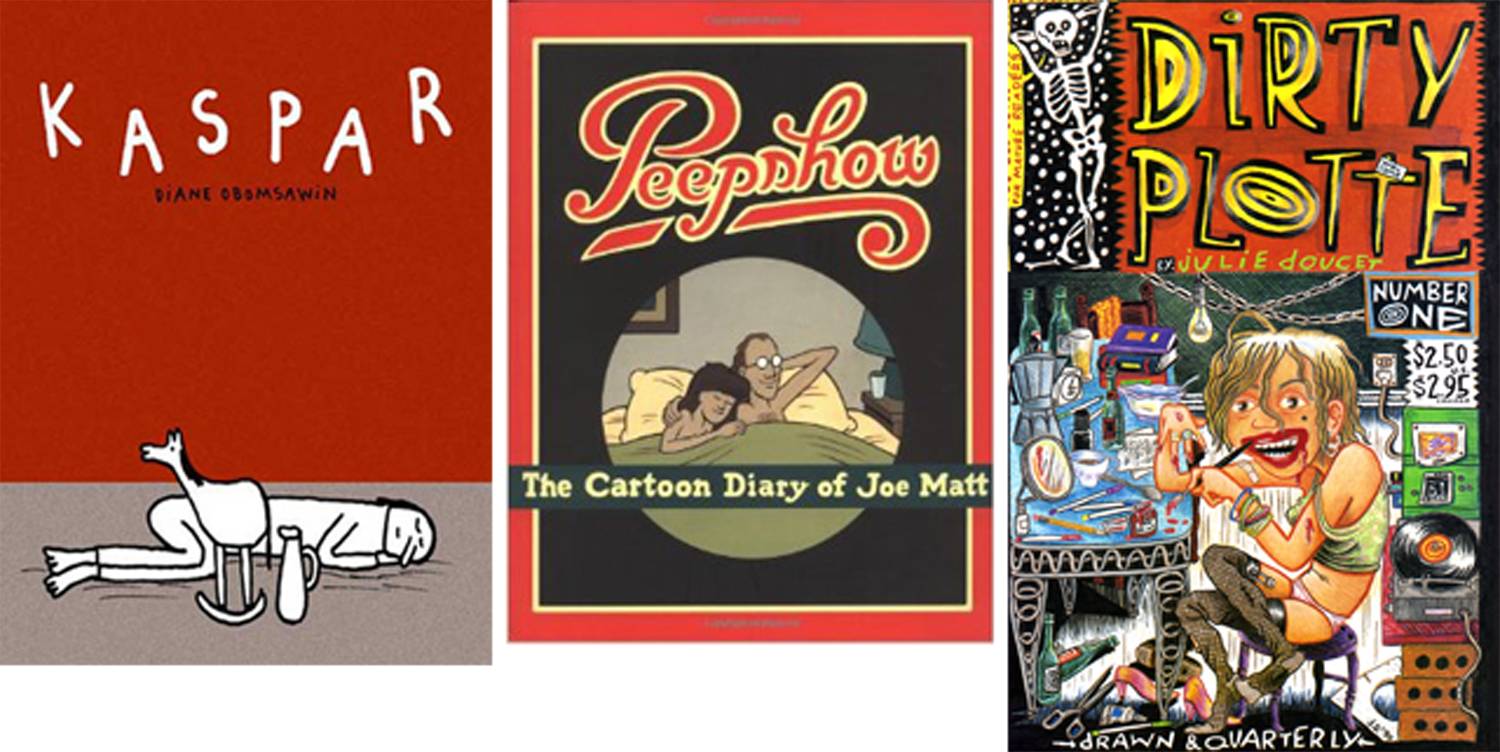

The first 10 issues, published in 1991 and 1992, featured what’s now recognized as a Hall-of-Fame lineup of cartoonists, including Julie Doucet, Joe Matt, Seth, Michel Rabagliati, James Sturm, Maurice Vellekoop, David Collier, Joe Sacco and Chester Brown – many of whom publish with D&Q to this day.

The press, establishing itself as an alternative to the alternative comics scene of the day, soon attracted a dedicated following.

“There was certainly a long period in the nineties when not just myself but other people I knew would buy anything that Drawn & Quarterly put out on faith,” says Bart Beaty, a comics scholar and professor at the University of Calgary. The work, he says, “was introspective but not aggressive. It was smart, but not always political.” He compares it to literary fiction, with “a very refined visual sensibility, and very rooted in the history of comics. I think they’re very cognizant of what constitutes the best work in the history of the medium, and they’re attracted to artists who are really immersed in that.”

Although D&Q and its authors quickly found acclaim, the financial realities of being a small, independent comic-book publisher were such that its long-term survival was never assured.

“In the early years, the company always was on the brink of bankruptcy, it seemed,” says Chester Brown. “There were lots of times when Chris couldn’t pay royalties on time, and that sort of thing.”

A key moment occurred in the fall of 2003, when Oliveros hired Peggy Burns, a publicist with DC Comics in New York whose own comic-book preferences were more in tune with D&Q’s offerings, to be in charge of publicity and marketing. Also coming to Montreal was Tom Devlin, her fiancé – they postponed their wedding to move to Canada – the publisher of Highwater Books, a fellow indie press, and a veteran of the publishing and comics industry. (When Highwater stopped publishing, several of its authors jumped to D&Q; Devlin joined D&Q full-time in late 2004.)

“It was really dodgy the first 18 to 24 months,” recalls Burns, 41. “Paycheques bounced, we delayed the fall season in 2004.… I would put a lot on my credit card and then be like, ‘Can I have a cheque? I need something.’ It was really hard.”

The irony is this was around the same time the idea of “graphic novels” was gaining widespread mainstream recognition – Chester Brown’s Louis Riel, published the same month Burns was hired, was the first D&Q title to land on The Globe and Mail’s bestseller list. Yet “we were scared, early on, Chris and I, that we would lose our authors,” says Burns, explaining the fear that larger publishers would poach D&Q’s talent, victims of their own success.

But, as Brown puts it, “the loyalty went both ways. [Oliveros] did things that I felt no other publisher would do.” He refers to when his book I Never Like You was reissued by D&Q; when it arrived from the printer, they discoverd the paper was translucent. Even though it had been Oliveros’s mistake, meaning he’d have to absorb the cost of a reprint, Oliveros “wanted the perfect book,” says Brown. “He cared about my book just as much as I did, and, in a way, maybe even more.”

This attention to detail, and an insistence on the best in production quality and design, became one of D&Q’s calling cards. Their books looked better than anyone else’s books.

As the decade progressed, an impressive list of contributors grew even more impressive: Chris Ware, Rutu Modan, Anders Nilsen, Guy Delisle, Miriam Katin, Daniel Clowes, Charles Burns and Lynda Barry, who credits D&Q with “saving [her] career as a cartoonist,” all put out work with Drawn & Quarterly. (Barry’s first book with D&Q, 2008’s What It Is, remains one of their bestselling titles.)

They branched out into art books and more experimental titles (the Petits Livres series), children’s comics and, with great success, increasingly brought the work of foreign cartoonists to North America. (Since 2006, for instance, they’ve sold more than 260,000 copies of the Moomin books by the late Finnish artist Tove Jansson.) They stepped outside comics, publishing the first two editions of junior style maven Tavi Gevinson’s Rookie Yearbook. They even opened a Montreal bookstore in 2007, Librairie Drawn & Quarterly, at 211 Rue Bernard, which has become a staple of the city’s literary community.

“I feel that Drawn & Quarterly has accomplished what I set out to do 25 years ago,” says Oliveros. “In many ways, beyond my wildest dreams.”

‘D&Q has always been aspirational’

Seth says he wishes there’d been a publisher like D&Q around when he was growing up. Artists who came of age in the nineties “had so many works they could look to as a direct inspiration of what to do. In some ways I envy that,” he says.

One of Oliveros’s goals in founding D&Q was to foster talent. Even back in the early nineties he was encouraging young cartoonists he admired, sending letters to the likes of Adrian Tomine, then a 19-year-old who was self-publishing his own work. Now, 25 years later, D&Q has been around long enough for the seeds sown in those early years to develop into a crop of new artists: Kate Beaton, Tom Gauld, Michael DeForge, Geneviève Castrée, Pascal Girard and Jillian Tamaki, who just released SuperMutant Magic Academy, her second book with D&Q, last month. Tamaki recalls combing the shelves for D&Q titles at her local library in Edmonton and discovering the work of Seth, Brown and others. “I learned how to cartoon from those books,” she says.

Beaton, whose 2011 collection Hark! A Vagrant is one of D&Q’s bestselling titles, shared a similar story, having first discovered D&Q books in the “super-tiny graphic-novel section” of Mount Allison University’s library and later, as a webcomic phenomenon, meeting Oliveros at TCAF in 2009.

“He took me to lunch and wanted to talk about books. That was the first time that a publisher, a real publisher, ever showed an interest in me,” she says. “They see potential in you, and they’re able to suss out something long-term out of you, even if you’re just starting. They really invest in comics and talent.”

Christopher Butcher, director of TCAF and manager of Toronto comic shop The Beguiling, says that “in Canada, D&Q has always been aspirational. When you want to tell a personal story, or when you want to tell a Canadian story, in your head you’re thinking, I’m going to tell this, and I’m going to get D&Q to publish it. That’s been my experience with many, many young cartoonists.”

‘A big family’

If Drawn and Quarterly is “like a big family,” as Chester Brown described the company to me earlier this week, then, in a sense, the family is losing its father.

A little more than a year ago, Oliveros pulled aside Burns and Devlin, his longest-serving co-workers, and told them he was thinking of stepping down, and that he wanted them to take over the company.

“It was a complete surprise,” says Devlin. “We kind of assumed he’d just do it forever.”

Burns says she burst into tears upon hearing the news.

“I’ve personally taken it as far as I can take it,” says Oliveros. “It would have been fine if I continued. It’s not like they were telling me to go or anything. I could have been around for the 30th anniversary, for the 35th, and the 40th, if I’m still alive, but I just feel, you know what, I don’t think I can accomplish – me, personally – I don’t think I can accomplish more.”

An artist first and foremost, Oliveros had long struggled to find the time to work on his own comics, which factored into his decision, too. (He’s self-publishing his first book, The Envelope Manufacturer, which will be out in January, though it will be distributed by D&Q. “I feel like I’m starting at zero with this,” he says. “I don’t want any favours.”)

“I don’t think that I took Chris for granted, but I just sort of took for granted that things would always continue as they were,” says Tomine. “I can only imagine the struggle that he’s gone through over the years of wanting to work on his own projects, but also having his life totally consumed by bringing the work of other artists into the world. I see it as an unselfish career that he’s had so far, of putting a higher value on the creative endeavours of other people, which not a lot of people with artistic ambitions are really capable of doing. I think it takes an unusual person to backburner their own artistic ambitions for the sake of promoting those of others.”

“It’s distressing to see him step down, actually,” says Seth. “I think all the cartoonists that have been there for a long time felt really bothered by that. It’s very hard to see him go.”

Burns will now act as publisher; Devlin will serve as executive editor. Oliveros, who is still figuring out his last official day in charge, will remain with the company as a contributing editor. He’ll have a desk in the new office, “but we’re urging him not to be there all the time,” says Devlin. “He did it for 25 years.”

Oliveros has been thinking about the past 25 years a lot lately.

It’s an overcast Tuesday morning, and we’re sitting in a coffee shop down the street from the D&Q bookstore, and only a few blocks away from the apartment where it all started. The anthology, which Devlin describes as a thank you, in a sense, to Oliveros, sits on the table between us.

“I feel really proud to have been a part of this,” he says. “The part of it that really seems unreal is just looking back and thinking, ‘My God, I can’t believe I was working with the very best cartoonists – the most talented people in their field, period – in the world.’ It boggles my mind. And as I’m coming to the end of this, I just think, ‘How did that happen?’ Honestly, I sometimes wake up – especially now, in the last couple of months – and I just think, ‘Is this real? Did this happen?’ Sometimes it almost seems like a dream.”