Malcolm Gladwell’s name doesn’t appear in any of the press materials or the wall panels for a new exhibition of drawings by Michelangelo opening Saturday at the Art Gallery of Ontario. But the best-selling author’s now-famous notion that it takes at least 10,000 hours of dedicated practice to make perfection is very much present in spirit. Indeed, the exhibition’s subtitle, Quest for Genius, is essentially a nod to the Gladwellian thesis that genius is less bestowal of nature, more feat of blood, sweat and tears.

Certainly Mick Buonarroti – Mick likely being the moniker Michelangelo would be called by were he alive today – expended more than his share of those precious bodily fluids (and much else) in an 89-year lifespan (1475-1564) that saw this lateral-thinking, light-sleeping workaholic master seemingly, well … everything – sculpture, drawing, poetry, architecture and, reluctantly (on his part, that is), painting. Drawing was especially foundational to the man’s creativity, something he purportedly did every day wherever he was, whatever the circumstance. “It was basically how he thought,” says David Wistow, the AGO’s senior interpretive planner who, with Lloyd DeWitt, the AGO’s curator of European art, is the primary developer of Michelangelo: Quest for Genius. Yet for all the artist’s voluminous output in chalk, pen and ink, only 600 or so authenticated Michelangelo drawings are known to exist today.

Thirty of these are on view at the AGO. Twenty-nine, including one double-sided work, are loans from the Casa Buonarroti, the Florentine palazzo designed and owned by Michelangelo (but never lived in by him), that his great nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, subsequently converted to a museum. By the time the master’s last direct heir died, in 1958, the casa was the largest single repository of Michelangelo drawings in the world. The other drawing, Studies of a Left Thigh and Knee, a Right Knee and a Right Foot (1550), is from the Thomson collection and as such is the only Michelangelo in the AGO’s permanent collection.

Thirty is generally regarded as the optimum class size in grade school – not too big and not too small. However, it’s a number the AGO seems uncomfortable with, or at least deems insufficient to affirming the genius and enduring relevance of the great Michelangelo. Perhaps, too, there’s a belief the drawings themselves, fragmentary that they are, lack the oomph today’s audiences supposedly require. Whatever the reasons, the upshot is that the gallery has chosen, peculiarly, meretriciously, to interlard Quest for Genius with 10 sculptures of varying sizes by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). While there’s no denying Michelangelo’s importance to the creator of The Thinker – he once called the Italian “my master, my idol” – the Rodins largely intrude and distract rather than enhance, particularly in the third and final exhibition space. Drawn almost exclusively from the AGO’s own collection, the mostly posthumous casts feel like a graft or jerry-built addition to what should have been a focused, rather intimate show about the pleasures of close looking. With Mick Jagger already in the house, why let Steve Tyler crash the party? And if the point is to demonstrate Michelangelo’s contemporaneity, might not the skinhead paintings of Canada’s Attila Richard Lukacs or, more provocatively, the cartoons of Tom of Finland or some (very) carefully chosen Lisa Yuskavage canvases better serve that point than artifacts by an artist dead for close to a century?

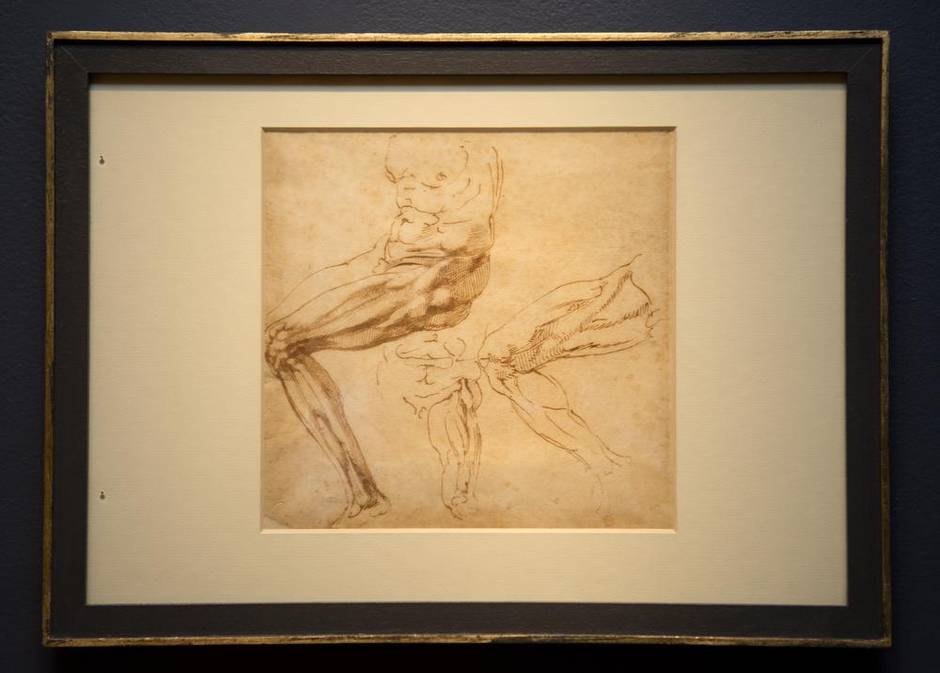

Half the Michelangelos here are figurative, the rest are architectural drawings for fortifications, libraries, façades and entrances. As ever with any exhibition where process rather than completion is the focus, the offerings are a mixed bag. Most visitors, I expect, will be most enchanted by the most realized figurative drawings. These include four famous works: the truly astonishing Madonna and Child, from 1524, the double-sided Cleopatra (1532-1533), Man’s Face, a red-chalk study from 1510 for The Flood fresco on the ceiling of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, and Studies for the head of Leda, the last prepared in red pencil circa 1530 for a painting subsequently destroyed because of its sexual explicitness.

Michelangelo once opined: “He who is not a master of the human body cannot understand architecture.” Be that as it may, the architectural renderings for the most part lack the unalloyed power of the figurative works. However, in a smart move, the AGO has enlivened the presentation of some of them by installing videos that show the buildings as they exist today. Thus, for Michelangelo’s first important architectural commission, the (still unbuilt) façade for the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, the artist’s 1516 riff, in red chalk, on the Arch of Constantine in Rome is superimposed on the extant arch. A 1561 multilayered drawing for another Roman monument, the Porta Pia city gate, is supplemented by images of several significant Toronto doorways, including that of the 1864 Don Jail, clearly indebted to Il Divino. In addition, LG Electronics has mounted two virtual-reality screens that realize, in quasi-axonometric fashion, Michelangelo’s unbuilt designs for the Laurentian Library in Florence and the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome. LG also has installed a large digital video wall that allows a visitor to more closely examine two architectural and three figurative renderings in the show.

The Rodin glitch aside, Michelangelo: Quest for Genius largely succeeds as an exploration of the all-too-human side of artistic greatness. Sometimes, though, it tries a little too hard to bring him down to earth. The headings on the wall panels, for example, have a melodramatic cast better suited to the chapters of a romance novel or the episode title cards in a silent movie. Here are a few: “Frustration in Love,” “Second Thoughts,” “A Great Disappointment,” “Misses and Hits” and “Out of Control.”

Michelangelo: Quest for Genius continues at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto through Jan. 11, 2015 (ago.net).

Editor's note

The drawing “Studies for the head of Leda” was produced circa 1530, not circa 1630 as stated in an earlier version of this article.