Before Beauty and the Beast, before The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, Pocahontas and Enchanted, there was The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Three decades ago, future Disney composer Alan Menken, fresh from his off-Broadway smash Little Shop of Horrors, agreed to score a musical based on Mordecai Richler’s breakout novel. The show had a brief run in Philadelphia but was never mounted again.

To this day, Menken – who has won eight Oscars, 11 Grammys and a Tony – insists Duddy Kravitz contains some of his best work. “I am determined, sometime before I pass from this planet, that that show [will] have its day,” he told an interviewer two years ago.

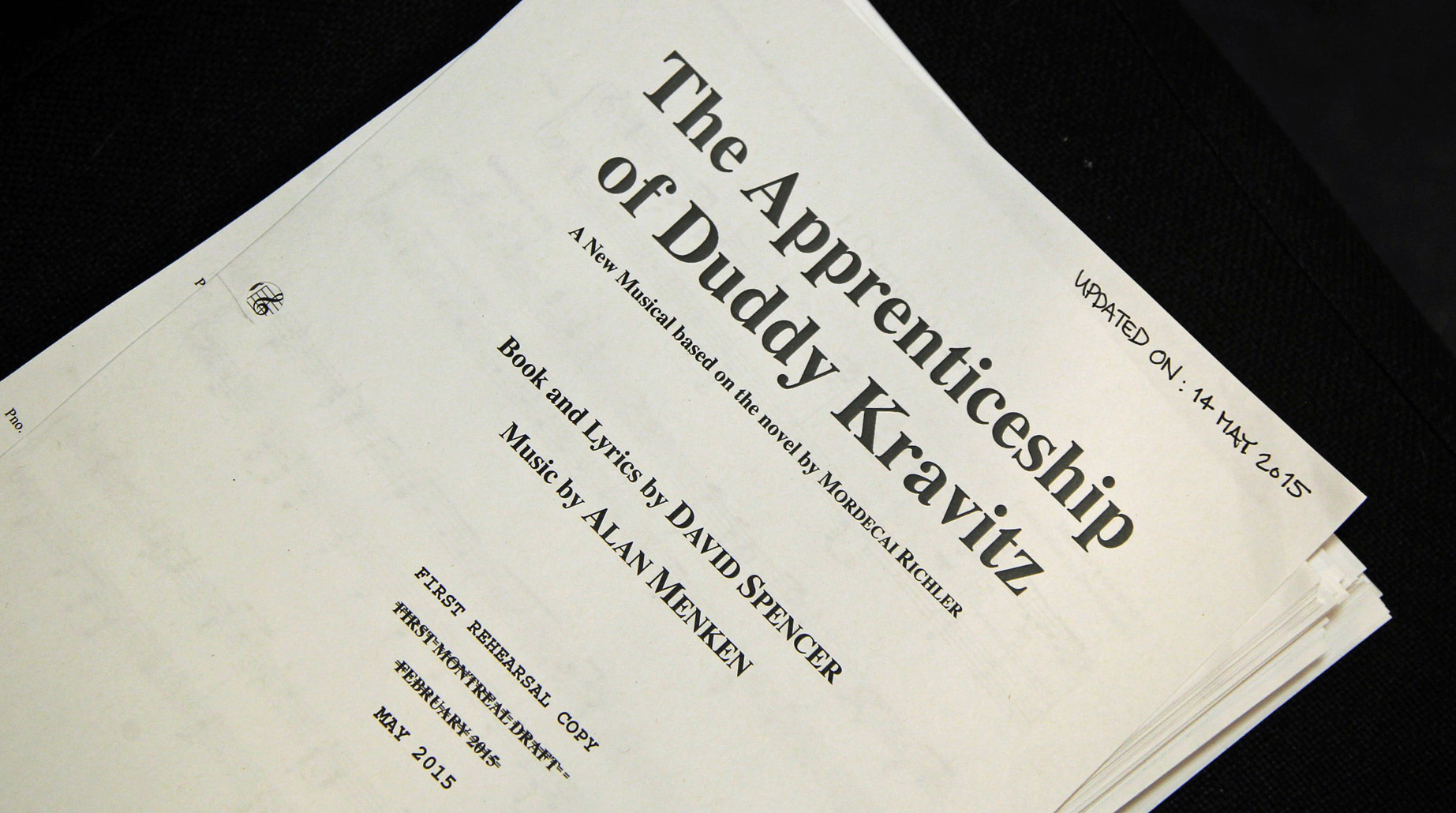

Next weekend, he finally will get his wish. On June 7, Montreal’s Segal Centre for Performing Arts will unveil an overhauled version of the Duddy Kravitz musical featuring Menken’s score and a script by the Philadelphia show’s lyricist David Spencer, author of The Musical Theatre Writer’s Survival Guide. Steppenwolf Theatre Company veteran Austin Pendleton, writer and director of the doomed 1987 Philly show, again sits in the director’s chair.

The story of Duddy Kravitz, the scheming St. Urbain Street antihero, has never lacked for big-name adapters: Richler’s friend Ted Kotcheff directed the 1974 film version. Rock and roll songwriting legends Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller wrote the score for another musical adaptation that failed in 1984. Broadway luminaries including directors Des McAnuff and Christopher Ashley have been attached to attempted revivals of the Menken show. There was even a third adaptation performed in Montreal – in Yiddish – 18 years ago.

But dramaturges have been consistently thwarted by Richler’s original text, in which Duddy betrays those closest to him. “You’ve got this wonderful character the audience wants to like,” says Stewart Lane, the producer who oversaw the Philadelphia show, “and at the end he does something so dastardly, it’s unforgiveable.”

Now, almost four decades after the first attempt to mount a Duddy musical, a cast of disparate characters (including Menken; a Canadian super-agent; a starstruck Montreal artistic director; and a wealthy yiddish schmatte merchant) are convinced they have the winning formula to help Duddy make the leap from page to stage – and achieve the kind of success the fictional schemer only dreamed of. But in their attempt to bring the musical to life, have the writers and producers sold out both the original story and its famously prickly author?

Richler’s first great character

The 1959 publication of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz marked a defining turn in the career of its 28-year-old author. With his fourth novel, a seminal work of Canadian literature, Richler “found his voice, and he found the voice that we all knew because he allowed himself to be as funny on the page as he was in real life,” says his biographer, Charles Foran. “Duddy was his first great character.’”

Duddy drew many themes from the early life of its author, who was born to an orthodox Jewish family in Montreal’s prewar immigrant ghetto east of Mount Royal. It was a unique cultural cauldron, equally alien to the establishment anglophone minority to the west and the disenfranchised, pre-Quiet Revolution francophone majority to the east.

The novel is a raw story of a nervy, relentless and crass hustler. Duddy is the second son of a widowed cabbie, dismissed by upwardly mobile Jewish contemporaries as a stereotypical pusherke (pushy Jew). Only his old-country grandfather appreciates Duddy, advising him: “A man without land is nobody.” Duddy singlemindedly pursues his dream of buying a lakeside property in the Laurentians with the help of his girlfriend Yvette. Through a series of comical misadventures – including a stint producing bar mitzvah movies – the conniving Duddy gets closer to his goal. Then out of desperation, he forges a cheque to pay for the last piece of land. The victim is his epileptic pal Virgil, who has been rendered a paraplegic after an accident for which Duddy indirectly bears responsibility. Duddy gets his land, but becomes estranged from his friends and loses his grandfather’s respect.

When director Kotcheff read the book, “I said, ‘Mordecai, not only is it the best Canadian novel that’s ever been written, but one day I’m going to go back to Canada and make a film of it,’ ” he says. “We laughed at the impossibility of such a thing.”

But Kotcheff would come through 15 years later. His jaunty, faithful film, co-written by Richler, is considered one of Canada’s best movies, anchored by a winning performance by a young Richard Dreyfuss. A schoolmate of Richler’s soon became convinced Duddy could thrive in another medium. Sam Gesser had also sprung from St. Urbain Street, becoming a successful music promoter. He brought Pete Seeger to Canada, and helped turn Leonard Cohen, Glenn Gould and Gordon Lightfoot into international stars. He was determined to make Duddy the toast of Broadway.

Richler happily sold Gesser the rights for $1 and in 1979, the impresario announced the debut of a musical Duddy the next year at Stratford, with Hair composer Galt MacDermot handling music and Richler collaborating. Instead, it took five years and a million-dollar budget for the show to reach the stage, debuting at Edmonton’s Citadel Theatre in 1984, with a score by rock legends Leiber and Stoller, and Broadway star Lonny Price as Duddy. But the show’s creators were inexperienced in the genre. The musical lacked good songs and the story was rough around the edges. Richler was also unhappy holed up in Edmonton, a city he despised for its harsh climate and lack of fine restaurants; he later labelled it the “boiler room” of Canada.

Dogged by poor reviews and weak sales, a planned Canadian tour was cut short. Gesser lost hundreds of thousands of dollars. But he was determined to keep going. Within months, Broadway legend Richard Maltby Jr. suggested Gesser hire Alan Menken, who had yet to score his first Disney musical, 1989’s The Little Mermaid. Menken in turn drafted lyricist and colleague David Spencer. Both were grandsons of Jewish immigrants from Europe, and were drawn to the story. “I connected with the material right away,” says Spencer. Price would reprise the role of Duddy, and the script would be rewritten by director Austin Pendleton, the original Motel the Tailor from Broadway’s Fiddler on the Roof.

Gesser was optimistic but “Mordecai was skeptical,” Menken says. “He felt there was a good musical in Duddy Kravitz, but, like many writers, wanted it to be true to what he wrote.”

Somebodies and coincidences

As the curtain fell on Saturday, Oct. 10, 1987, the audience at Philadelphia’s Annenberg Center jumped to their feet. Yet the enthusiastic response to Duddy Kravitz filled Pendleton not with joy, but dread. He knew what awaited him backstage.

Three years after the Canadian show fizzled, Gesser managed to get the Menken-led version of Duddy to Philadelphia, the first step to a Broadway debut. But the show had one big problem: the ending. Duddy’s lack of redemption, faithful to the book at Richler’s behest, upset audiences. Some audience members talked back to the stage when Duddy forged the cheque. The ending, Pendleton told a critic at the time, is “heavy stuff” that many theatre-goers “don’t want to face up to.” Worse, the show’s backers decided to pull out after Philly. If the producers couldn’t find another financier, the show wouldn’t get to Broadway.

Producer Stewart Lane suggested Pendleton drop the curtain several minutes early, after a rousing Menken ballad sung by Yvette called Welcome Home. The song typically “brought the house down,” Spencer wrote in a 17-page summary of the show’s history. “Then the show continued toward its dark ending. When it got there, audiences … suddenly turned furious. And rightfully too, because we denied the potential for Duddy’s redemption that the song had clearly dramatized.”

Pendleton gathered the cast together to break the news. “There were howls of outcry,” he recalls. “I said, ‘It’s just to try to secure a future for it, this gives us time [to fix the ending] if we can get the money.’ ”

The Saturday show closed with Welcome Home and met a standing ovation. When Pendleton went to congratulate the actors backstage, “they were in a rage,” he recalls. “They were saying, ‘How can you even seem happy?’ I said, ‘I don’t want to be a slut, but it got a standing ovation.’ ” The director promised they wouldn’t do it again.

But the next day, Lane asked Pendleton if he would again end the show after Welcome Home. Pendleton balked, saying it was supposed to be a one-time deal when potential investors were in the house. “Stewart said, ‘I can’t believe that a thing would work like that and you wouldn’t do it again.’ I said, ‘You’re right.’ ”

With five minutes to go, the cast learned they would again perform the shortened version. “There were people slamming doors, running down the hall in a rage,” Pendleton recalls. Once again, though, the show got a standing ovation. “It was like this weird dream where all your dreams are coming true, except it’s a nightmare,” Pendleton says.

Richler, who had distanced himself from the show, “grudgingly accepted that we might continue to experiment with the ending, but we’d better be careful,” Pendleton says. But Richler also worried “that if the ending changed, everybody in the literary world would think less of him,” Spencer says. He wouldn’t consent to further compromised endings. And so the Philly production died – but Spencer and Menken weren’t ready to give up.

Menken optioned the rights to keep developing Duddy, and Spencer took on the librettist role, restarting the script. The two then embarked on a 20-odd year creative odyssey to give the musical new life. Spencer wrote and rewrote. Menken altered more than half the music. The biggest change was the ending. After years of tinkering, Spencer says he “discovered, finally, that I needed to preserve not the ending, but the moral point.” Spencer felt Duddy needed to find redemption (unlike in the book) to restore the balance needed to satisfy musical audiences. But to avoid betraying the novel, that redemption had to come at a price, with Duddy understanding the cost of his actions.

Editor’s note: The next paragraph contains a spoiler revealing a plot point from the musical

In the novel’s pivotal moment, Duddy forges Virgil’s signature on a cheque, calls the bank impersonating his friend, then goes to claim the money supposedly on his behalf. In the new Spencer-Menken version (spoiler alert), Duddy forges the cheque, calls the bank – but runs into Virgil and Yvette as he heads out. Duddy confesses his intent. Virgil writes him a cheque out of the goodness of his heart. Duddy gets his land but loses his grandfather’s respect. By the play’s close, his friends are willing to forgive him. Duddy is ready to accept their anger. “Who could love Duddy Kravitz?” he asks. “That would depend, Duddy,” Yvette answers, “on what you really want now.” With that she offers him a modest life with her, singing Welcome Home.

Spencer “found an ending that can work that doesn’t ignore the ugly part of” the story, says Pendleton. “You can’t leave out what the original ending was. But you can’t leave them with that ending, either.”

Still, the musical remained unstaged. Richler passed away in 2001, and Spencer never shared his new ending with the author. In the early 2010s, Michael Levine, the Toronto-based lawyer, agent and adviser to the Richler family, decided to help Spencer and Menken bring their revamped show to stage. “I said … I’m acting only for [the Richler estate], I’d be happy to be helpful to you,” says Levine. He approached the Stratford Festival, David Mirvish, Theatre Calgary, the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, the Shaw Festival. Everyone passed on it.

The main barrier was cost. Musicals are expensive to mount, and risks are high for unknown shows – particularly for those with a troubled past. But Spencer’s stubbornness, much like that of his St. Urbain Street protagonist, never waned. “We never wanted to let it go,” he says, “because it wouldn’t let go of us.”

Becoming a somebody

Lisa Rubin is lost in the moment. It’s early February, and the Segal Centre’s 37-year-old executive and musical director is leaning over a cocktail table at the complex, eyes closed and head bowed as she clutches her iPhone, listening to a song that will be performed here in four months.

“I’m leaving St. Urbain Street / For where I’ll get me some money in hand / To invest in a business that’s grand / That’ll stake me for getting some land / And then I’ll be somebody.”

Rubin looks up with compassion in her eyes. “He just wants to be a somebody,” she says. “How can you not love him?”

Rubin has become a somebody, and quickly. A lifelong musical theatre junkie and professional actress who spent a decade performing various roles at the Segal, Rubin was thrust into her dual position last year at the financially strained arts centre (formerly known as the Saidye Bronfman Centre) after two senior departures.

Rubin admits she “came out of nowhere” to lead one of Canada’s prominent theatre institutions. “Even she didn’t believe what she could do,” says benefactor Alvin Segal, the men’s suit merchant who hand-picked her. But it is largely due to Rubin’s determination that the Menken-Spencer version of Duddy will finally have its day. “She’s a star as far as we’re concerned,” says Menken’s manager, Rick Kunis. “Lisa helped to make it all go through.”

The new Duddy show was also helped by an odd confluence of events. One was the moment when Spencer spotted a familiar face while watching CBC’s Republic of Doyle. It was early 2012, and the lyricist noticed his protégé, Newfoundland musical director Jonathan Monro, on the show. When Monro learned that Spencer was a fan of the police drama, he asked if Spencer could contribute anything for a Newfoundland Pops concert featuring Doyle star Krystin Pellerin. Spencer offered three Duddy songs. During rehearsals in Newfoundland, Spencer and Monro began talking about collaborating. “I impulsively said, ‘Man, if you can get Duddy going, you can musical-direct that,’ ” Spencer says.

Filled with renewed hope for his pet project, Spencer found himself chatting later that year about the show with Canadian actor Elan Kunin. It was a remarkable coincidence. Kunin had starred as Duddy in the one successful musical adaptation of Richler’s novel – an entirely different version staged in Yiddish at the Saidye Bronfman Centre in 1997. In another twist, Kunin had gotten to know Spencer after reading a copy of his how-to musical theatre book given to him by his wife, none other than Lisa Rubin. Kunin suggested to Spencer that the Segal was the right venue for his show.

In October, 2013, Rubin met Spencer for lunch in New York; one hour later they reached a tentative agreement to stage Duddy at the Segal. “It was one of the most bullshit-free meetings I’d ever had,” Spencer says. Rubin, who was a teenage “fansie” of Menken’s 1992 musical Newsies, didn’t have to think twice. “If you were told that you could world-premiere an Alan Menken musical, would you want to hear if it’s good before [agreeing]? Please.” (She even threw the Segal’s Yiddish theatre’s schedule into disarray to accommodate the new show: They were coincidentally set to restage the 1997 Yiddish Duddy show that very season, and Rubin had to find a replacement.)

With nine of its 14 professional actors from outside Montreal, and an American director – Pendleton agreed to return – Duddy Kravitz is a costly gamble for a theatre company with a $4.5-million annual budget. Rubin says the show’s $350,000 cost is at the top end for a Segal show and “we’re going over.” Even if it sells out, Duddy will lose money. But she’s confident the show will be a hit with Montrealers, and dreams it will get to Broadway. “We are hopefully going to give the musical theatre world a gift, and it will be a Montreal story, started at the Segal Centre.”

Time provides spaces

It’s May 14, and the Segal staff is busy preparing for a fundraising gala with a special appearance by Menken, who has flown in to perform a medley of hits. Downstairs, Pendleton watches as the new Duddy, actor Kenneth James Stewart, rehearses a tense scene. Slouched in a corner is Spencer, looking younger than his 60 years. This is the first week of rehearsals and Spencer doesn’t want to miss a minute; he has already been spotted by cast members tearing up.

“I get these contemplative moments of quiet awe,” he says later. “Everybody in this place … they get the show, they get what it’s about, and the cast couldn’t be better.”

With his narrow blue eyes, angular face and slicked, dirty blond hair, the slight 29-year-old Stewart looks the part of Duddy, hungry and sly. Off stage, Stewart casts a different impression. He is a shy, sweet everyman, like the title role he performed in You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown at Stratford in 2012. “Ken has a duality to him,” says Monro, Duddy’s musical director. “Duddy needs to be impulsive and unpredictable. At the same time we want to love him and say, ‘Don’t do that!’ Ken brought that.”

But one thing the Alberta-born actor didn’t bring to the production was prior knowledge of the novel. He admits he’s never read anything else by Richler. He’s not alone.

Duddy Kravitz was widely taught to Canadian students for years as a “classic mid-century immigrant” novel to expose them to “these other Canadas,” says Foran. The book has since fallen off many curriculums, supplanted by other immigrant narratives such as Joy Kagawa’s Obasan.

The passage of time and the passing of the author may give the musical the room to assert itself as a standalone piece of art. Still, there will be purists who say Menken and Spencer betray the source material. Florence Richler, the author’s widow, plans to attend the show’s Montreal opening, and feels audiences should be “mature enough to accept the ending” her husband intended, but is also realistic. “As Mordecai once said, once you’ve sold the rights to a book … you can protest but you have no rights any longer,” she says.

Menken acknowledges “there will be a variety of reactions. I think David has accomplished a show that will appeal to Richler purists – if they like musicals. If they don’t like musicals, that’s another thing entirely.”

There could be another happy ending: a so-called “merging of rights,” whereby the Segal show becomes the legally designated Duddy musical that can be performed as an off-the-shelf production by anyone. That has never been the case for any past production, as the Richler estate protected the source material. Levine is non-committal but says, “I’m working my butt off to help [Menken] make things work,” and ensure that the show helps to preserve Richler’s legacy. Future productions would also mean royalties for the Segal, offsetting its losses.

While Rubin and others dream of Broadway, Spencer and Menken are just happy to see their show staged. “Whatever happens – if it lasts three weeks and closes, if nobody does it again – I’ll be happy enough that it’s the show I wanted it to be,” says Spencer. Menken jokes, “I still keep waiting for the call that says, ‘Uh, gee, just kidding, it’s not going to happen.’ ”

As for Richler, his widow thinks her late husband “would be secretly pleased, pour himself a handsome Macallan and get on with whatever he was working on.”

Sean Silcoff is a reporter for Report on Business and the co-author of Losing the Signal: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Blackberry.