About five or six years ago, Joel Greenberg, the artistic director of the Toronto theatre company Studio 180, left a bunch of voicemails for the New York-based writer David Rakoff. He had read all of Rakoff’s work – collections of piquant essays and hilarious first-person journalism with knowing titles such as Fraud, Don’t Get Too Comfortable and Half Empty – and he wanted to offer him a gig. Rakoff didn’t call back, but Greenberg tried one more time, and finally reached him.

“I knew he’d written film, and he loved theatre, and I thought the way he sees the world might be a perfect fit for our company,” Greenberg recalled recently. “I said, ‘Have you written a play? We’ll commission you to write a play,’ and he said, ‘Oh! No no no no – I love theatre too much. I could never do that. I’m really sorry.’ And that was my meeting with David Rakoff.”

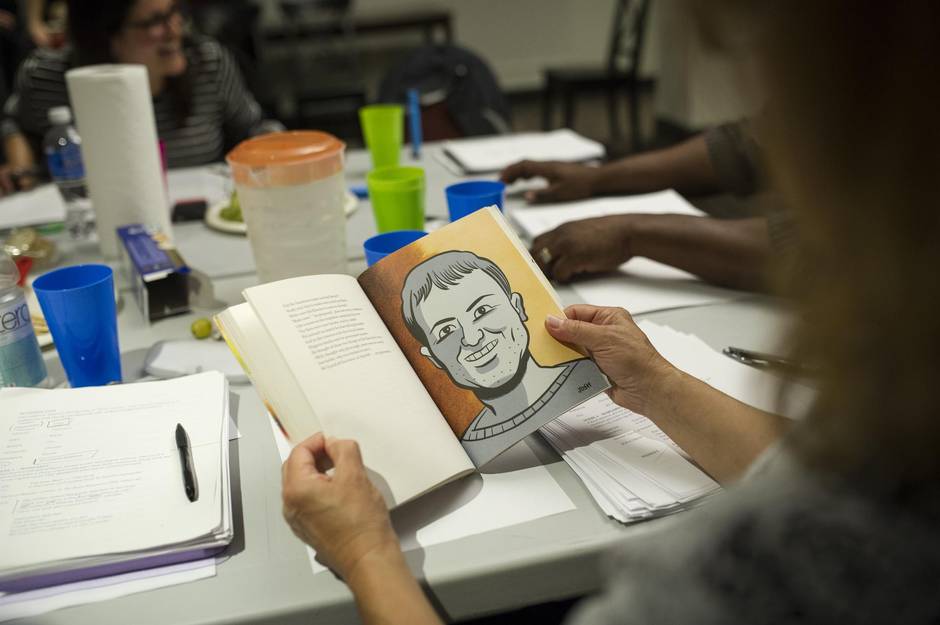

This Thursday, however, Rakoff will become a produced playwright of sorts when Studio 180 mounts a one-night-only staged reading of his only work of fiction, Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish. Seven actors, including Greenberg, will read Rakoff’s work accompanied by some minor theatrical adornment: sound and lighting effects; images from the book projected on screens; and incidental music written and performed by Rakoff’s brother-in-law Tom Bellman.

The book, both epic and intimate, comprises a connected series of exquisitely observed character portraits that span the 20th-century. It is a unique, almost sui generis achievement: a very adult story (privation, domestic abuse, sexual molestation, extramarital affairs, abortion, the 1980s San Francisco gay scene, AIDS, etc.) told in a Seussian, sometimes childlike verse.

Describing an artist dying of AIDS, Rakoff wrote:

But, just like a child whose big gun is a stick,

Cliff was now harmless, he’d gotten too sick

To take any action beyond rudimentary

Routines that had shrunk to the most elementary:

Which pill to take now, and where is your sweater?

Did the Imodium make you feel better?

Study your shit to make sure you’d not bled.

Make sure the Kleenex is next to the bed.

“Make sure,” “be prepared,” plan out every endeavour

Like a scout on the stupidest camping trip ever.

If it was an unlikely novel, Love, Dishonor seems a natural for the stage; certainly, at least, it aches to be performed. When it was published in the summer of 2013, critic Carl Wilson, writing in these pages, observed that the urge to read the book aloud, “feels a little embarrassing, kind of childish and vulnerable, which is precisely the ambition of this bravura exercise: to take the risk of dancing on the thin membrane between satire and sobriety, between literature and doggerel, in hopes of breaking through to the nakedly sad and ridiculous truth of what living is like. And yes, dying too.”

The mention of dying was unavoidable, because the book’s publication was overshadowed by the fact that Rakoff, who was born in Montreal, grew up in Toronto, and moved to New York in 1983, died of cancer in August, 2012, at the age of 47. He had finished writing Love, Dishonor about five weeks earlier.

The book’s launch in July, 2013, was something of a wake. About 60 of Rakoff’s friends, family and others (including writers Sarah Vowell, Melissa Bank, Augusten Burroughs, Simon Doonan, and the This American Life radio host Ira Glass) took turns reading passages for a standing-room only crowd at a downtown Barnes & Noble. Rakoff took part, too: the audience listened to a clip of him from the audio book he had recorded only weeks before his death. There were tears.

Rakoff had done another performance a few months before he died. As part of a This American Life stage show beamed live to a few dozen cinemas in North America, he read an essay about the toll that cancer was taking on his body; toward the end, he broke away from the lectern and performed a dance created for him by the New York choreographer Monica Bill Barnes.

As Greenberg developed his adaptation of Love, Dishonor, one of Rakoff’s associates suggested he incorporate some of the footage of that dance into the show. But he realized that would take the piece into a different, mawkish realm. “I didn’t want to turn it into a memorial service. I was feeling tremendous pressure to honour the book, not to suddenly come off as David’s closest friend who’s finally getting around to a public grieving.”

And so the Studio 180 production, which is sold out, holds the tantalizing possibility of being the first time Love, Dishonor might finally be able to step out of the shadow of Rakoff’s death and be judged on its own merits. (Though not its full merits: Greenberg and director Mark McGrinder, who collaborated on the adaptation, cut roughly 25 per cent of the book in order to get the running time down to about 90 minutes without an intermission.)

One Sunday afternoon a few weeks ago, McGrinder and the seven actors gathered in the party room of Greenberg’s midtown Toronto condo to do a table read of the script. They had already gone through it once that day, and McGrinder was giving notes before a second run-through. “We’re telling a story, we’re sharing it,” he reminded the actors. “Almost think of it as a children’s story, but not quite – and it would be terrible it if were!” A few of the others laughed quietly.

Later, Greenberg said he didn’t think most of the actors were even aware at first of the bittersweet history of Love, Dishonor. They were simply responding to it as a piece of art, as Rakoff had originally intended.

“There is a surprisingly redemptive quality in the book, that he didn’t write about [in his essays], and that didn’t attract him,” Greenberg noted. “His point of view was so clear and so funny, and so deeply cynical. But [Love, Dishonor] is none of that.”

He reconsidered his words. “I mean, it has all of those pieces. But it’s a humanized way of seeing the world that wasn’t revealed when he was writing non-fiction.”