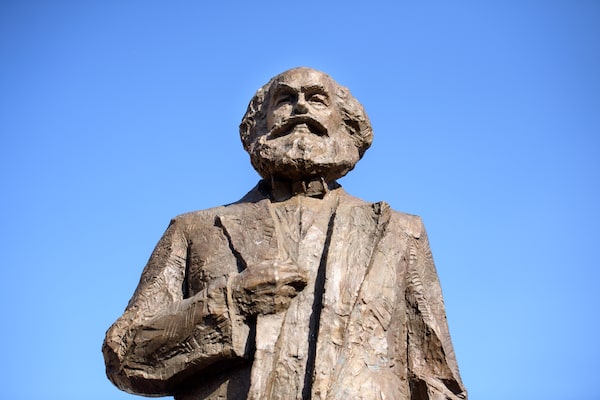

The sculpture of German philosopher and revolutionary Karl Marx pictured on the 200th anniversary of his birth on May 5, 2018, in Trier, Germany. Marx is seen as one of the fathers of communism, but was also involved in the London Stock Exchange.Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images

In the 19th century, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels authored The Communist Manifesto and a number of other books that urged workers to unite and throw off their chains. Both individuals consequently became known as the fathers of communism.

What is less well known is that the fathers of communism also traded on the London Stock Exchange. Marx was a bit of a day trader (to use a contemporary term) and Engels managed a large portfolio of mainly blue-chip stocks for many years.

Let’s start with Marx. In the spring of 1864, he came into some money when an admirer bequeathed £820 to him. This was a considerable sum back then, far more than Marx earned from his writing. No time was wasted on spending the money – the family home was renovated, pets bought for the kids and vacations taken.

But not all funds were directed toward consumption. As Marx writes in a letter to his uncle Lion Philips in the summer of 1864:

“I have, which will surprise you not a little, been speculating … in English stocks, which are springing up like mushrooms this year … and are forced up to quite an unreasonable level and then, for the most part, collapse. In this way, I have made over £400. ...

One biographer claims Marx decided to try his hand at financial speculation after hearing of the killing that German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle was making on the stock market. Another biographer suggests that some encouragement was provided by Engels (who was part owner of a cotton mill and knowledgeable about business matters).

Further on in his letter to his uncle, Marx says that he is going to do some more trading:

“… now that the complexity of the political situation affords greater scope, I shall begin all over again. It’s a type of operation that makes demands on one’s time, [but] it’s worthwhile running some risk in order to relieve the enemy of his money.”

There is no record of how he fared. If we go by the perennial tendency of traders to proclaim their winnings but not their losses, we might conjecture that the capitalists got the better of him and successfully retrieved their capital.

Then again, maybe not. The Peking Youth Daily claimed in 1992 that his stock dealings were put aside when he got involved in the founding of the Communist International. “But pity that his capital was too small,” the publication lamented.

What about Engels? He had some investing savvy thanks to his business background, which included a seat on a stock exchange. When he retired in 1870 at the age of 49, his portfolio was worth, in today’s money, about £1.2-million ($2-million), according to British historian Tristram Hunt in The Frock-Coated Communist. When he died 25 years later, it was worth the equivalent of £2.2-million. Holdings included shares in the London and Northern Railway Co., South Metropolitan Gas Co., Channel Tunnel Corp. and Foreign and Colonial Government Trust Co.

During retirement, Engel’s portfolio produced an income sufficient to cover his living costs, as well as provide Marx with an annual subsidy of £380. This effectively gave both men membership in the rentier class, which many communists despise.

Engels had a rationale for why it was okay to be a rentier. It went like this: Trading stocks “simply adjusts the distribution of the surplus value.” It doesn’t expropriate it from the workers.

Engels and Marx closely monitored business conditions. A letter between the two in 1852 illustrates:

“The minor panic in the money market appears to be over, consols [a type of government bond] and railway shares are again rising merrily, money is easier. ... I don’t believe that the crisis will this time be preceded by a rage for speculation … crucial ill-tidings from overstocked markets must surely come soon. Massive shipments continue to leave for China and India … Calcutta is decidedly overstocked … I don’t believe prosperity will continue beyond October.…”

This tracking of macroeconomic fluctuations may have had something to do with wanting to know when the workers’ uprising would occur (they believed it would be triggered when the economy collapsed into a depression). But it likely also had something to do with gathering intelligence that would assist with managing their investments.

The financial sections of socialist newspapers won’t do as sources of information. Indeed, Engels once declared: “I am not so simple as to look to the socialist press for advice on these operations. Anyone who does so will burn [their] fingers and serve [them] right!” Instead, both men were devoted readers of the Economist magazine and other serious business publications.