Everyone knows that “you can’t fire me – I quit!” is a joke.

It doesn’t matter if you planned to resign; you got let go first. It’s just one of those cases where, whatever what you say after the fact, there are a set of pre-existing terms and conditions that render any subsequent narrative manipulation on your end null and void. You probably can’t put that job on your resume. Someone beat you to the punch. Don’t let the door hit you on your way out.

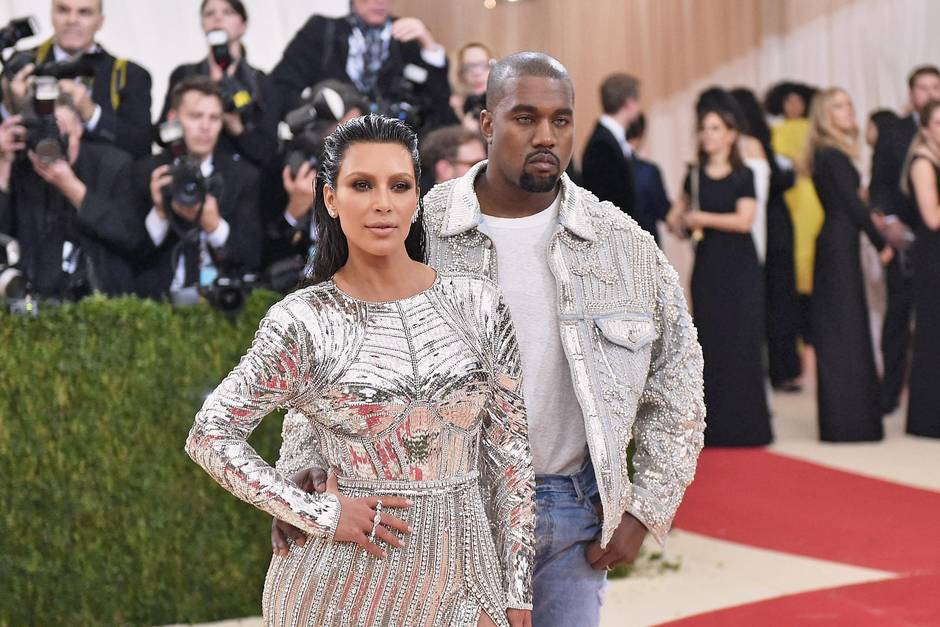

Earlier this week, Kim Kardashian “leaked” a recording of Kanye West’s phone call with Taylor Swift in which the rapper asked the pop singer for her approval of the lyric, “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / Why? / I made that bitch famous,” which appears on his song Famous. Swift can be heard giving her blessing.

But when the song came out, she condemned it, claiming she’d never heard it, and how could she approve something she’d never heard? And in a GQ profile of Kardashian released this June, Swift’s reps doubled down on that claim.

But Kardashian’s Snapchat recording seemed to put the whole thing to rest: Taylor Swift was, effectively, fired months ago.

There’s a lot of hay being made over Kardashian’s involvement in this, with some calling the imbroglio just the latest example of two prominent women being pitted against one another (this is only marginally valid). There’s also much sympathy for Swift, given the misogyny inherent to West’s lyric (valid) and claim to her fame (even more valid still).

But putting all of that – the back-and-forths, the sexism – aside for a second: how could Swift ever have thought she was going to control a narrative involving Kardashian, queen of reality manipulation?

That’s what it’s all about, after all: steering the conversation. With Kanye and Swift, this started back in 2009, when he stormed the stage at the MTV Video Music Awards to declare Beyoncé’s – not Swift’s – music video one of the greatest of all time.

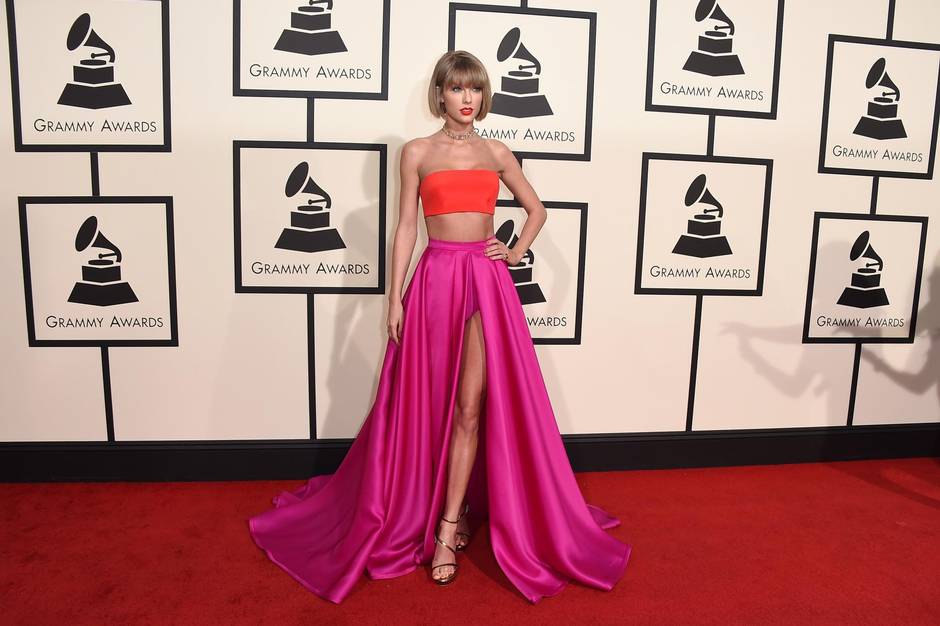

Swift took the reins in 2015, presenting Kanye with the Video Vanguard award at that year’s VMAs. And the relationship remained in neutral territory long enough for him to write Famous and run it by her. But then, when the song came out, Swift apparently changed her mind; she claimed the conversation never happened. She claimed she’d been victimized.

Which brings up a second over-quoted adage: “crying wolf.” It’s all the more easy to discredit Swift’s attempt at steering the conversation when her method for doing so more often than not is to make herself the victim, albeit speciously.

She did it last year, when Nicki Minaj accused the VMAs of racism, not-so-discreetly suggesting they nominated Swift over her for Video of the Year because Swift is white. At the time, Swift attempted to redirect a conversation about racism toward, essentially, herself, accusing Minaj of pitting women against one another; it was feminism-as-narrative control, from the singer behind the blatantly woman-hating Bad Blood.

With Famous, Swift’s problem was, at first, his claim to her fame. When Kardashian’s recording dispelled that, she changed her story, saying she didn’t like being called a bitch. She’s also troubled by having been recorded without her consent. Yes, that’s terrible. But if you get caught in a lie, saying you didn’t know you were being watched doesn’t mean you didn’t tell the lie. It means your backpedalling just hit a coaster brake.

For Swift to agree to her own victimization – however satirical it exists within the track Famous – would be a complete divergence from her personal brand, which capitalizes on victimhood. She’s constantly the jilted lover; the betrayed BFF; the hard-fighting feminist. But maybe – just maybe – the Kardashian-leaked phone call has pulled back the curtain. Swift is writing a narrative, too, but her prose is not very consistent.

Which is all to say Swift is out of her league here. Just look at the very fact that Kanye recorded the phone call, that Kardashian thought to post it on Snapchat just seconds after the end of an episode of Keeping Up with the Kardashians, which focused almost exclusively on the Famous fallout. The Kardashian-Wests are masters of narrative manipulation. For West, it’s been a matter of convincing the world that he’s an autodidactic, multitalented, greatest-of-all-time genius. For Kardashian, it’s been making good reality TV.

So whether or not there’s any validity to Swift’s claim that her real issue is being called a “bitch” – whether or not West actually asked her if she was all right with his claim in the song that he made her famous (Kardashian’s Snapchat story doesn’t explicitly contain this line, though Swift can be heard making what sounds like a reference to it – even here, Kardashian’s apparent sixth sense for editorial continuity is remarkable) – she pulled a soccer dive in front of Kardashian and West’s combined 70-million social-media referees, and Katy Perry, too.

It’s all theatre, anyway, and it’s particularly well-played. The fact is that West and Kardashian had a recording of the phone call just waiting in the wings throughout all the tweets, speeches and GQ profiles. And Swift may finally have figured that out.

In an Instagram post written shortly after Kardashian’s phone-call leak, Swift appeared to put a nail in her own coffin : “I would very much like to be excluded from this narrative,” she wrote. At last.