‘Brendan?” he shouted from upstairs.

“Yes, Dad.”

“Are you able to help me with the, uhhh, um, what’s it called … the CD player?”

“Yes, Dad. But remember? I just need an hour to finish this article that is due tomorrow. It’s really important that I get this done.”

“Oh, okay. I’m sorry. I forgot.”

“That’s okay.”

Five minutes later, a knock on the door: “Brendan, don’t forget that we need to look at the CD player. Make sure it’s not broken.” A growing anxiety in his voice this time.

“Yes, Dad. I know. And it’s not broken,” I say, doing everything in my power to control my irritation.

“Okay, well then can we have a quick look at it now?”

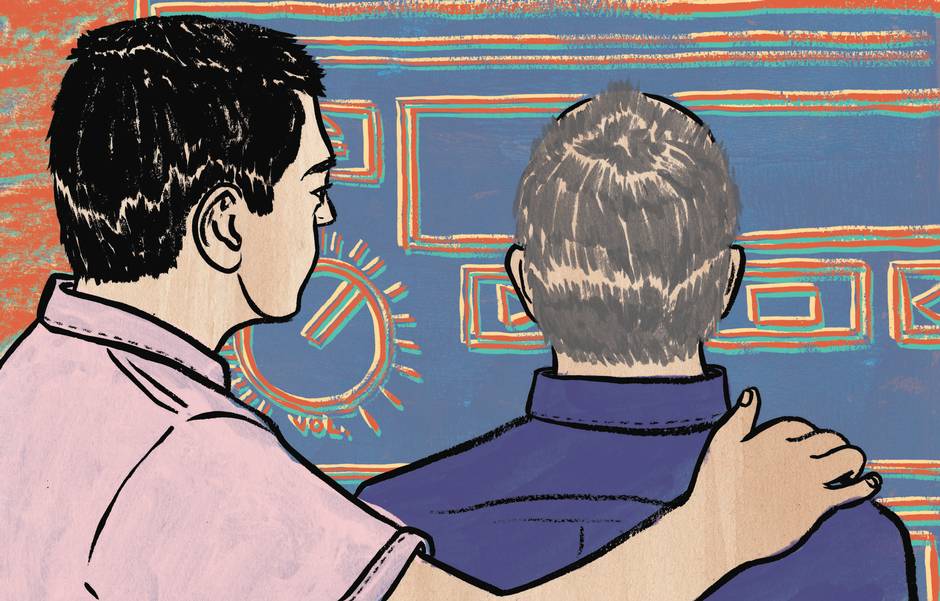

I bite my lip in frustration. Why can’t I just be left alone for an hour? I drive him everywhere, cook for him, make sure he’s comfortable, moved across the country to be closer to him. But I can’t get an hour to do my work?

Sigh. My needy, obsessive, selfish father. But then I remember: Be patient. It’s not his fault. No matter what you are dealing with, he is going through worse.

It had been three years since the worried whispering, “What’s wrong with Rick?” began among friends and family, and a year and a half since the diagnosis – Parkinson’s disease, Lewy Body Dementia, probably Alzheimer’s, too. A neurological triple threat.

Dementia is relentlessly progressive. Unless you have personally witnessed its devastating effects, it is difficult to fathom the enormous weight of those words. With the illnesses’s onslaught, my father’s life has become a chronicle of losses. Two summers ago, it was his ability to drive. Nine months ago, his capacity to get dressed and out the door without assistance. The assault on his language has been particularly acute. The once-brilliant storyteller is no longer able to keep track of the plot. The tenacious debater is now found wanting of a rebuttal.

This week it was something new. Apparently, my father was destined to lose his ability to independently enjoy music – one of his life’s simple pleasures. But I heard something else in his voice: defiance. He is stubborn and a fighter – he was going to go down swinging. I took a deep breath and dug in. Strategic thinking is one of the first casualties of dementia, so I wrote down step-by-step instructions.

1. Plug the CD player in. The plug is on the wall next to the phone.

2. Turn on the power to CD. The switch is on the right-hand side of the CD player.

3. Select the CD you want to listen to.

4. Press the Open button on the CD player. It is the button that says “Open” on it.

5. Place the CD in the CD player and close it.

6. Press play. The play button is on the front of the CD player and says “Play.”

The next 20 minutes were a test of patience.

“Yes, the plug on the right. No, your other right. You have to put the CD in before you press Play. Good job, but that’s not the CD, that’s the flashlight. Power button is on the right. Nope, that’s the radio, but good job.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be sorry, you’re actually doing really well.”

“Okay, thanks.”

He kept trying, but each time a new issue would trip him up. After a while, he slumped in his chair, his face wasted with exhaustion. I looked into his eyes. There it was, that glazed look. Not quite here, but not quite gone either.

“I think I should rest. It’s okay, Brendan. We can look at the machine again later. Do we have any Jujubes or wine gums?”

Instead of relief, all I could feel was sadness. My father, defeated. But this quickly turned into defiance.

“You were really close that last time, Dad. I think you will get it soon.”

His eyes lit up. “Oh, okay. Let’s try it once more.”

I spent another 15 minutes walking him through it. When I was about ready to give up, he finally got all the steps correct. I asked him to do it again, twice in row. Success! The awful country music my dad used to torture me with blared from the player, filling the room – and my heart – with joy. With Dad occupied, I was able to get time to myself and finally get some work done.

A story from Greek mythology that always stuck with me is the myth of Sisyphus, who was forced to spend an eternity pushing a rock up a hill, only to have it fall back down. For the remainder of his life, my father is condemned to push the rock of his remaining memories against a progressively steeper slope of forgetting.

The next morning, the rock came crashing down. Once again, a knock on my door. “Brendan? I think the CD player is broken again.”

Dementia is a tedious affair. Basic tasks morph into monumental challenges, and each day brings new forms of frustration and heartache. Sufferers and caregivers alike are confronted with dozens of temptations to simply give up. And yet, we seldom do. From a distance, this may seem futile. After all, it is. But at a deeper level, there is a constant resistance, a struggle to assert your dignity – despite the odds. Dad won an important battle that afternoon.

Brendan Wright lives in Ottawa.

Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.