Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

On summer evenings, I spend much of my time staring at leaves. Milkweed leaves, specifically. I'll be out for a walk with my children when I see a patch of milkweed and dash off, leaving the kids waiting impatiently while I examine the plants.

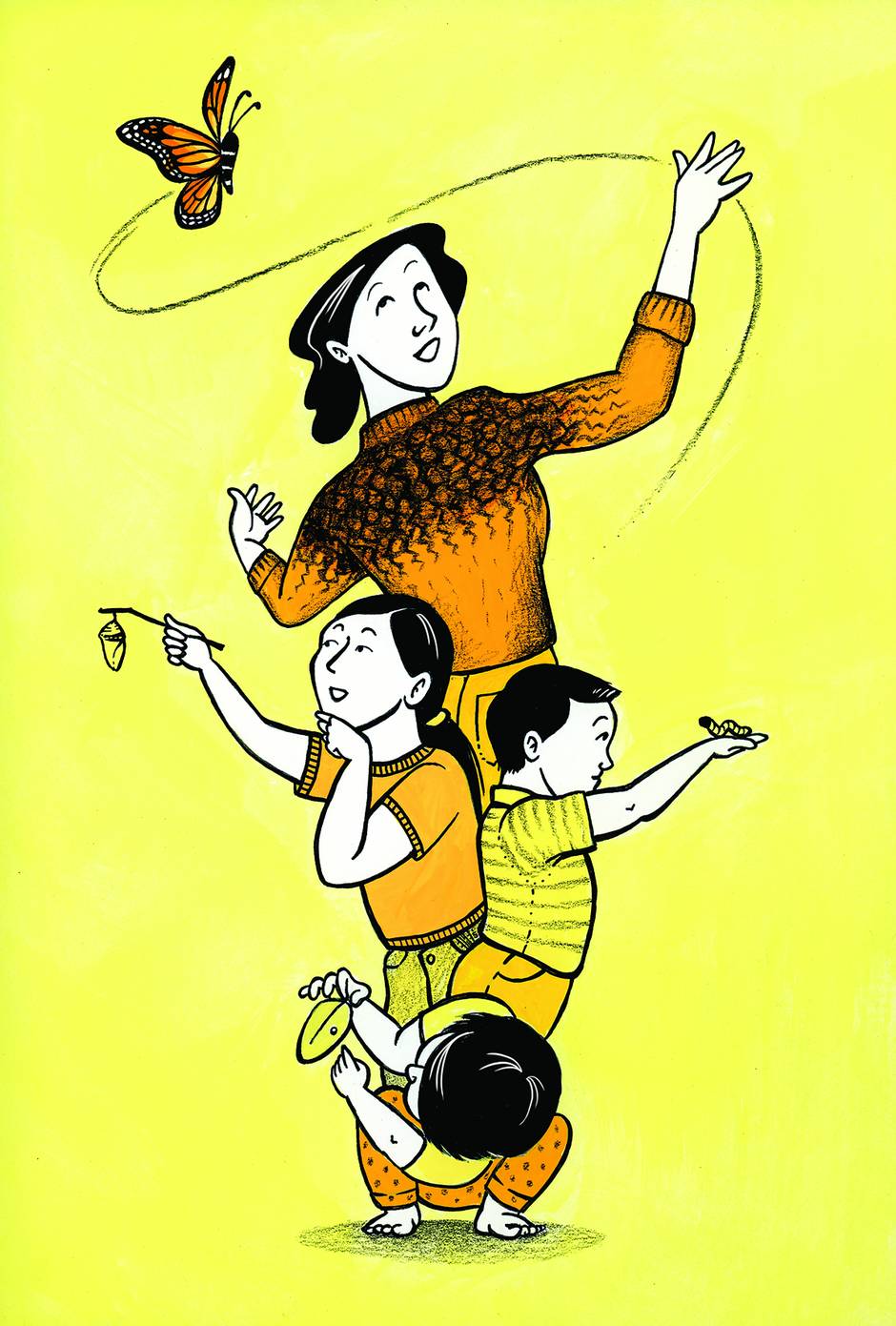

What I'm searching for are the eggs of the monarch butterfly. They're easy to identify once you've seen a few: small, ivory-coloured beads on the underside of milkweed leaves. Female monarchs can lay hundreds of eggs in a day, which is just as well because the odds of a caterpillar emerging from that egg and living long enough to turn into a butterfly are dismally low – about one in 20. If you find an egg, you can increase its likelihood of survival dramatically by taking it home and protecting it from predators while it goes through its larval and pupal stages, then releasing it when it becomes a butterfly.

From mid-summer until mid-September for the past four years, my life has revolved around my caterpillar collection.

It's not the kind of hobby I ever expected to take up. I have considered myself "concerned about the environment" since Grade 6, but until recently I was concerned from a distance – signing petitions, writing to politicians, donating to environmental groups, that sort of thing. I'm not inclined to be an outdoorsy person: I was too squeamish to spend my childhood catching frogs or letting spiders wander over my hands. I was even a little uncomfortable picking up my pet gerbil.

But a few years ago, I signed up for a parent-child gardening program. One of the leaders brought in a monarch chrysalis and I was astonished at the sight of it. They are stunningly beautiful, like a small, smooth piece of jade with a ring of shining gold dots around the top. Shortly after that, my friend Nikki encouraged me to hunt for butterfly eggs with her, and gave me a quick education on monarchs and their near-threatened status as a species.

I came home from our trip with four eggs. Within days they’d hatched and we had four impossibly tiny caterpillars, barely visible on the leaves. They were like tiny snips of grey thread. But they were hungry and they needed fresh food, so I went out to get more milkweed. While collecting leaves, I found – surprise, surprise – more monarch eggs. And having found them, I discovered I was unable to leave them behind to face their likely death.

Soon, there were too many to keep in our Tupperware containers and I invested in a mesh caterpillar-rearing cage. My husband looked at it with dismay.

“Do we have to keep them in the kitchen?” he asked. “What if they get out?”

“They won’t escape,” I said, waving dismissively.

Actually, they did. Several times. I didn’t tell him when this happened.

The creatures changed daily and I was fascinated by their rapid growth. Within a few days, they were more than a centimetre long, striped, with little antennae visible. A few days more and they were great fat things, spending all day munching on their leaves. You could actually hear them chew. Then one day they became silent, hung upside down from the top of the cage and the next time I looked they had each turned into one of those beautiful chrysalids I had earlier admired.

When they finally emerged as butterflies, it happened when my back was turned. It was like a magic trick, pulling a rabbit out of a hat – in this case a butterfly out of thin air. The kids and I opened the enclosure and watched them fly off on their long migration to Mexico.

“Adios! Adios, mariposa!” yelled my daughter, jumping up and down as they flew out of sight. She turned to me and explained, “In Mexico, they speak Spanish.”

Since then, I’ve gone hunting for eggs every year. This summer I raised 20 caterpillars, and while it’s not a huge job it involves a certain amount of effort. Besides the frequent excursions for fresh milkweed, there’s a lot of cleaning involved; monarch caterpillars produce an astonishing amount of poop – known as frass – and the bottom of the container must be wiped out daily. Sometimes they go wandering up the side of the container and must be gently coaxed back onto a leaf for their own good. Try reasoning with a caterpillar – it requires the gentlest touch and a significant amount of patience.

On websites dedicated to raising monarchs, some enthusiasts claim to raise 300 or more in a season. My mind boggles at the amount of frass they must have to clean up. I’m not willing to go that far – at least not yet. I have three children to look after.

But I’ve grown fond of this yearly ritual. The transformation that takes place is so rapid, striking and beautiful. And watching this has changed me a little too. Raising caterpillars has been a kind of gateway activity for me – for my whole family, really – to become more involved in nature. We’ve gone bird banding, tried some hikes on the Bruce Trail and built a bat house for our backyard.

I discovered a new joy in the natural world that I’d never experienced before. And every time I see a monarch flying by, I wonder if it’s one of ours.

Catherine Jansen lives in Oakville, Ont.